Introduction………………………………………………………………………………. 3 1. Formation of a system of compulsory labor ………………………. 5 2. Peculiarities economy forced labor ……………………. 8 3. Manifestations of the mobilization economy using the example of the construction of hydroelectric power stations……………………………….. 16 Conclusion……………………………………………………………… ………… 27 References………………………………………………………. 29 Introduction The main foundations of the communist regime in USSR It is generally accepted to consider total political and ideological control over public...

5303 Words | 22 Page

Labor Economics

abstracts 1. Peculiarities offers labor in Russia. 2. Peculiarities demand for work in Russia. 3. Using the model " work - leisure" for the analysis of Russian market labor . 4. Model of home production and the possibility of its application in Russia. 5. The role of the household in USSR and in modern Russia. 6. Investments in human capital in Russia: directions, peculiarities , Problems. 7. Problems and prospects for investment in education in Russia. 8. Analysis of the elasticity of demand for work on market educational...

1298 Words | 6 Page

Features of the labor market in Russia

« Peculiarities formation and functioning market labor in Russia" Completed by: student of the FC1-4 group Mutaliev Muhammed H. Scientific supervisor: Doctor of Economics, Professor Vafina Nailya Khaevna Moscow 2012 Plan: Introduction 2 Chapter 1. Market labor : essence and models 2 1.1. Concept market labor , its essence and structure 2 1.2. Peculiarities functioning market labor in conditions of perfect and imperfect competition 2 Chapter 2. Peculiarities formation and functioning market labor...

7949 Words | 32 Page

labor economics

Russia in the international market labor Abstract on the discipline "Economics" labor » Completed by: group student 6-E-2 Full name Shumilova M.V. Head: Vinogradova V.V. St. Petersburg 2016 Contents Introduction 3 1. Foreign economic relations of Russia. 5 1.1. The role and place of Russia in world trade. 5 1.1.1. Import device. 6 1.1.2. Export structure. 7 1.2. Russia at the international market labor . 7 2. Export of labor from Russia 9 2.1 General peculiarities labor export...

3063 Words | 13 Page

Forced labor in the economy of the USSR

Soviet times, allows for a deeper exploration of the social history of that society. The social composition and structure of Soviet society were different complexity, heterogeneity and diversity. His feature during the Stalinist era there was a high proportion of prisoners forcibly brought to labor . The duration of stay in the camps - for a significant number from 10 years and above, turned persons serving sentences into a stable social group with its own way of life, internal...

6666 Words | 27 Page

Main features and trends in the development of the labor market in Russia and developed countries

COURSE WORK In the discipline “Economics” labor » Topic: “Basic peculiarities and development trends market labor in Russia and developed countries” CONTENTS Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………...3 1. main models of national markets labor and labor relations…..6 2. Current trends in the development of labor relations in developed countries……………………………………………………………………16 3. Labor ex relationship USSR …………………………………….....................................

7546 Words | 31 Page

Features of the development of trade in Russia, France and Germany in the 19th – 20th centuries.

Astrakhan State Technical University Peculiarities development of trade in Russia, France and Germany in the 18th – 20th centuries. Astrakhan 2008 Economics as a science in Western Europe began to take shape in the 17th-18th centuries. in close connection with the development and strengthening of the capitalist mode of production. Attempts to develop a consistent economic concept that explains the causes of foreign trade and its place in the economic life of the country began to be made with the liquidation of feudal...

6364 Words | 26 Page

Image of Russia on the international labor market

HR IMAGE OF RUSSIA INTERNATIONALLY MARKET LABOR In modern conditions of accelerating globalization of the world economy, it is of great importance For Russia, its entry into the global economic space, an integral part of which is the international market, is gaining labor . Russia entered the international market labor quite recently - about a quarter of a century ago. Over the years, the nature of the flow of foreign labor to Russia has changed, the scale of legal employment of Russian labor has increased...

1366 Words | 6 Page

Development of management in the USSR and Russia

improving local self-government. Building socialism in USSR demanded the creation of a new public management organization socialist production. In the first years of Soviet power they gained great fame works such scientists as A.A. Bogdanov, A.K. Gastev, O.A. Yermansky, P.M. Kerzhentsev, N.A. Amosov. Famous Soviet scientist A.K. Gastev worked on improving the theory and practice of organization labor . He formulated and substantiated a concept called...

1577 Words | 7 Page

Features of the historical path of the USSR and Russia

GBOU SPO "Samara Medical College named after. N. Lyapina" ESSAY on the topic: " Peculiarities historical path USSR and Russia" Completed by: Student 0215 group Department: "Nursing" Sargsyan Ruzan Subject: History Teacher: Varlamenko V.V. Samara, 2014 USSR in the same way, Russia has always occupied and is occupying its own special place in the world. Russian civilization is neither Asian nor European. This is a special border...

639 Words | 3 Page

Abstract on the history of Russia. Perestroika and collapse of the USSR.

Abstract on the history of Russia. Perestroika and collapse USSR . Introduction 1. On the way to "perestroika" 2. "Perestroika": in search of ways ""improving socialism"" 3. "Perestroika" crisis and collapse USSR Conclusion Literature INTRODUCTION 1. ON THE WAY TO “PERESTROIKA” The Soviet system of central planning functioned for almost 70 years. The main planned goals included carrying out from the late 1920s. socialist industrialization at a rapid pace and the achievement on its basis of military...

3020 Words | 13 Page

Perestroika in the USSR: plans and reality

cultural studies and history Perestroika in USSR : INTENTIONS AND REALITY Completed by: student 514 Semenova E. Yu Contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………3 2. Strategy and tactics, goals and program……………… ……5 3. socialist perestroika 4. Stages of perestroika……………………………………………………….9 5. The final stage of perestroika. Decay USSR ……16 6. Plans and achievements…………………………………...

3479 Words | 14 Page

Management in the USSR and Russia

in socio-political life this is a transition from totalitarianism to democracy, in economics - from an administrative-command system to market , in life transformation of an individual person from a “cog” into an independent subject of economic activity. Such changes in society, the economy, and our entire way of life are difficult in that they require changes in ourselves. The importance of management was especially clearly realized in the thirties. Even then it became obvious that this activity had turned into a profession, a field...

2211 Words | 9 Page

Industrialization of the USSR

Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………….……10 List of references. Introduction Industrialization USSR USSR USSR from a predominantly agricultural country to a leading industrial power. Although the main industrial potential of the country was created later...

2282 Words | 10 Page

Features of the tax system in the USSR

"St. Petersburg State Mining University" Department of Economics, Accounting and Finance. CHECK WORK Finance on the topic: « Peculiarities tax system in USSR » COMPLETED BY: 3rd year student IUP and IP Group 934-01 Code 9701131083 Vasin VV CHECKED BY: Atabieva E.B. St. Petersburg 2012 CONTENTS: INTRODUCTION 1. TAXATION IN USSR In 1917 - 1941 1.1 The first steps after the Great October Socialist Revolution. INTRODUCTION...

7029 Words | 29 Page

Industrialization: its prerequisites, main stages, results. Features of the formation of the industrial economy in France in the 19th century.

On the topic: Industrialization, its prerequisites, main stages, results. Peculiarities the emergence of an industrial economy in France in the 19th century. Completed by a 2nd year student, group EBH(b)2-12: K.K. Checked by senior teacher: D.D.K. Bishkek-2013 Plan. Introduction 1. Industrialization…………………………………………………………………...4 1.1. Its prerequisites, main stages, results……………………… ……………....5 2. Peculiarities the formation of the industrial economy in France in the 19th century...8 Glossary………………………………………………………………………………………...

1915 Words | 8 Page

The policy of “War Communism” and the NEP in the USSR

sources 16 Test 17 Introduction 20s of the XX century, especially their first half, led to the emergence of the first sprouts of new political thinking, although the term itself was born in our time. But it was the 1920s that in practice brought about a combination of new economic policies, democratization, pluralism with successes in peaceful coexistence. The path was opened to non-violent peace and the construction of socialism in USSR without social catastrophes, on the basis of “civil peace”. Both could...

3099 Words | 13 Page

Migration in the world of work

Contents Introduction 1. Labor resources and their use 2. Unemployment 3. Market labor 4. Population migration 5. Objectives of the Government Russian Federation in the field of labor resources and in the social sphere List of references Introduction Regional economics is one of the most important branches of economic knowledge. Regional economics studies the natural resource potential of Russia and its regions, population, labor resources and modern demographic problems, analyzes the starting level of the economy...

3061 Words | 13 Page

Taxes in the USSR

HUMANITIES AND ECONOMICS COLLEGE Report on the topic: “Taxes in USSR 1917-1991" Completed by student Tufanova Kristina Maksimovna Group 08181 Checked by Alimurzaeva Irina Ivanovna Veliky Novgorod 2012 Taxes in USSR (1917-91) As a result of the revolution that took place in February 1917...

6366 Words | 26 Page

Features of marketing development in Russia

Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..…….. 3 Peculiarities marketing development in Russia……………………………………..………... 4 The origin of marketing in the era of the Russian Empire (1880-1917) ..………………….… 4 New economic policy (04.1921 – 10.1929) ………………………………………………………. 4 Khrushchev’s thaw ………………………………………………………..…………….. 5 Start: perestroika (1986 – 1991) ………………… …………………..……….……….…… 6 Epoch market …………..………………………………………………………...…………… 11 Anti-marketing stereotypes……………………………… ……………………………...

10126 Words | 41 Page

Features of supply and demand in the labor market

and credit" PECULIARITIES SUPPLY AND DEMAND IN RUSSIAN MARKET LABOR Coursework in the discipline “Microeconomics” Completed by: Student of group 59 “D” Yu.O. Agafonova Head Associate Professor T.B. Surzhikova Omsk 2010 Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………….........3 1. Conceptual approaches to analysis functioning of modern market labor ……………………………………………………………………………….……5 1.1. A neoclassical approach to analyzing the functioning of modern market labor …………………………………………………………………………………...

6945 Words | 28 Page

Russia on the global labor market

World labor market…………………………………………………………………………………..…………………………….4 | | |1.1. Concept, peculiarities ……………………….……………………………………………………………………………………….4 | | |1.2. World market labor , labor force reproduction: peculiarities in modern | | |conditions…………………………………………………………………………………………………………|conditions……………………… …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...

7341 Words | 30 Page

In which jobs is it prohibited to employ women?

use is prohibited labor women? Work women is regulated by both general and special rules of law. It's connected with the need to establish additional guarantees for this category of workers. Prohibited use labor women in hard work and work with hazardous conditions labor , as well as in underground work, except for some underground work (non-physical work or work on sanitary and consumer services). List of heavy work and work with hazardous conditions labor where it is prohibited...

1401 Words | 6 Page

Collapse of the USSR

democratization of society 6 ♣Reforms in the economy 7 ♣Glasnost 10 ♣Reforms of the political system 13 Consequences of perestroika. Decay USSR 17 ♣Disintegration USSR 19 Conclusion 23 Literature 24 INTRODUCTION The topic of perestroika and collapse USSR especially interesting because at the moment it is difficult to find a person whose fate would not change significantly in connection with the reforms of M.S. Gorbachev...

7805 Words | 32 Page

"Perestroika" in the USSR

"PERESTROYKA" IN USSR PLAN 1. Causes of “Perestroika” Gorbachev’s role in the implementation of “Perestroika” Brief overview of the state Soviet economy in the period from 1975 to 1985 2. Goals and results of “Perestroika” Democratization of society Implementation Consequences Reviews 3. “Perestroika” as the main reason for the collapse USSR Reasons for the collapse USSR Consequences of collapse USSR for Russia and the world community Processes in the CIS and in Russia in modern times...

4437 Words | 18 Page

Features of reforms in the management and regulation of foreign economic activity in Russia.

Peculiarities reforms in the management and regulation of foreign economic activity in Russia. Main stages of development of management organization foreign economic activity Former socialist countries have a lot of work ahead of them to transform the super-monopoly structures characteristic of a centralized, command-administrative economy into competitive, efficiently operating, entrepreneurial structures. This process is extremely difficult , contradictory and time consuming. Conversion problems...

1991 Words | 8 Page

FEDERAL EDUCATION AGENCY BELOVSKY INSTITUTE (BRANCH) GOU VPO "KEMEROVSK STATE UNIVERSITY" DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Role USSR in the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance DIPLOMA THESIS 6th year students of OZO Specialty “history” ...

20307 Words | 82 Page

Development of the Russian labor market in the context of globalization

Development market labor of the Russian Federation in the context of globalization Specialty - 08.00.14 "World Economics" ABSTRACT of the dissertation for the degree of Candidate of Economic Sciences Moscow-2000 The dissertation was completed at the Department of Statistics and Finance, Faculty of Economics, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE WORK The relevance of the topic is determined by the following. Work appears before...

6570 Words | 27 Page

Modern trends and features of the development of the global transport services market

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 CHAPTER 1. MODERN TRENDS AND PECULIARITIES WORLD DEVELOPMENT MARKET TRANSPORT SERVICES 5 1.1. The place and importance of services in the economy and foreign trade of modern states 5 1.2. Transport law and transport legislation 12 CHAPTER 2. LEGAL REGULATION OF TRANSPORT SERVICES 17 2.1. Legal problems of transport and forwarding activities 23 CONCLUSION 28 REFERENCES USED 29 INTRODUCTION Relevance of the course work. In recent decades...

5731 Words | 23 Page

Comparative analysis of the socio-economic development of the USSR and European countries in the 80s of the XX century

Federation State educational institution of higher professional education Kazan National Research University named after. A.N.Tupoleva Abstract on sociology On the topic: Comparative analysis of socio-economic development USSR and European countries in the 80s of the XX century Completed by: student gr.2411 ...

4889 Words | 20 Page

USSR Customs Service

Contents Introduction 1. Foreign economic activity USSR in the 80s 2. Customs policy USSR in the 80s 3. Customs Code USSR 1991 as the logical completion of the stage of foreign economic reform (1986-1991) Conclusion Literature Introduction In post-revolutionary Russia and subsequently in the USSR, the process of formation and development of customs affairs and legislation on it was complex and contradictory. In general, during the period from October 1917 to 1991...

5468 Words | 22 Page

Liquidation of the USSR and formation of the CIS Russian Federation as the legal successor of the USSR

Test No. 1 on the history of a student of group MOSM-291 Roshchin Boris Dmitrievich Test No. 1 Option No. 19 Question No. 1 Expansion European Union, the formation of the world " market labor ", NATO's global program and Russia's political guidelines. European Union enlargement is the process of enlargement of the European Union (EU) through the entry of new member states into it. Sometimes the enlargement process is also called European integration. However, this term is also used when speaking...

2744 Words | 11 Page

“Formation and development of the banking system in Russia. Problems and prospects of the Russian credit market"

UNIVERSITY OF COMMUNICATIONS" Department of "Economic Theory" COURSE WORK in the discipline "Macroeconomics" on topic: “Formation and development of the banking system in Russia. Problems and prospects of Russian market credit resources" Contents Introduction. 1. The concept of the Russian banking system 2. The history of the formation...

5268 Words | 22 Page

Reforms of the USSR

Reforms in USSR in the 20s - 30s 1. The policy of “war communism” 2. NEP: reasons for its introduction and essence 3. Industrialization industry USSR 4. Collectivization of agriculture 1. Policy of “war communism” “War communism” is a system of temporary, emergency measures forced by civil war and military intervention, which together determined the uniqueness of the economic policy of the Soviet state in 1918-1920... Forced to carry out life "military-communist"...

11354 Words | 46 Page

The collapse of the USSR and its consequences

Test No. 1. Topic: “Disintegration USSR and its consequences" Work plan: 1. Introduction. 2. Material impoverishment of the population in conditions of economic crisis. 3. Rising unemployment and impoverishment of workers. 4. Social protection institutions and self-organization of the population. 5. Insecurity as a state and as a process. 6. Conclusion. Introduction One of the most significant events of the last ten years was the collapse of the Soviet Union and the formation of 15 independent states on its territory...

2297 Words | 10 Page

World economy - world labor markets

economics on the topic: “World market labor » Chelyabinsk, 2009 CONTENTS Introduction 3 1. World market labor . 5 2.International population migrations 13 3. State regulation of labor immigration. 16 4. State regulation of international labor migration in donor countries. 21 5. Main centers of international labor migration. 26 Conclusion 30 References 32 Introduction Along with international market goods and services, with market capital is gaining more and more power...

5884 Words | 24 Page

Economic reforms in Russia (USSR) in the period of the 30s - 40s. XX century

ST. PETERSBURG STATE POLYTECHNIC UNIVERSITY Department of Regional Economics ABSTRACT ON DISCIPLINE ECONOMIC HISTORY Topic: Economic reforms in Russia ( USSR ) in the period 30's - 40's. XX century Performed by student gr. 10710/20 Voronina O.A. (Full name) (Signature) Head, (academic degree, position) Zaichenko I.M. (FULL NAME.) ...

3029 Words | 13 Page

Peculiarities of work of women and persons with family responsibilities

relationships. Such a high assessment of the relevance of this problem is explained by the relatively high level of female unemployment in the country, low demand for women on market labor , the complexity of the demographic situation and the traditionally double workload experienced by working women in Russia. The question of legal regulation labor The issue of women has ceased to be only a domestic matter; it has long since assumed an international character. There are a large number of legal acts adopted...

4885 Words | 20 Page

Labor Economics

instant communication between remote points of the planet. Transnational capital knows no borders, and transnational companies open their branches in those countries where the location of these branches promises the greatest profits. Integration trends especially noticeable in Western Europe, where the Schengen agreement practically erased state borders, and the introduction of a single currency further emphasized the commonality of the economic space. Integrative trends concern not only the movement of goods...

6327 Words | 26 Page

Collapse of the USSR

Was the collapse of the Soviet Union inevitable? 1 WHAT WE LOST AND WHAT WE GAINED AS A RESULT OF THE CORRUPTION USSR What happened in Beslan September 1-3, 2004, did not leave a single citizen of the Russian Federation indifferent. There is no limit to outrage. And again the question arises: why was there no such rampant terrorism in the Soviet Union as is observed today in the Russian Federation? Some believe that the Soviet Union simply kept silent about such terrorist acts. But it's an sew in the bag...

4825 Words | 20 Page

collapse of the USSR

1 1. Socio-economic prerequisites for the collapse USSR : 1.1 Disintegration processes in USSR ...................................2-5 1.2 Reforms of the political system in USSR ................................6-8 1.3 An attempt to strengthen the executive power.......... ...................9-12 2. Decay USSR and the “parade of sovereignties”................................13-15 3. Consequences of collapse USSR : 3.1 Economic consequences.................................................... ..

4473 Words | 18 Page

collapse of the USSR

Introduction 1. Socio-economic prerequisites for the collapse USSR 1.1. Disintegration processes in USSR 1.2. Political reforms systems in USSR 1.3. Attempt to strengthen executive power 2. Collapse USSR and “parade of sovereignties” 3. Consequences of collapse USSR 3.1. Economic consequences 3.2. Political consequences Conclusion List of references Introduction Disintegration processes began in the Soviet Union already in the mid-1980s. In that...

4424 Words | 18 Page

Collapse of the USSR

State educational institution of higher professional education Ural State Law Academy Institute of Prosecutor's Office Department of Theory of State and Law Test work on the subject “Political Science” On the topic “Disintegration USSR » Completed by: Borisenkov A.V. student of group 209 of the Institute of Prosecutor's Office Checked by: Saenko P. A. ...

4530 Words | 19 Page

Technical standardization of labor at the enterprise.

rationing labor at the enterprise. Contents: Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………2 Contents……………………………………………………………… …………..3 1. Stages of scientific technical standardization work. 2. Varieties of norms labor : standard time, standard production, standard service, standard service time, standard number. 3. Production standards labor (ENiR, VSN, VNiR, TNiR, USN, GESN, etc.) Analytical part……………………………………………………………………………….13 1. Give examples of calculating standards labor . 2. Reflect...

3551 Words | 15 Page

Collapse of the USSR

ethnic conflicts. As a result, armed clashes escalated into interethnic wars. Attempts to solve the problem of nationalism with the help of troops are not led to positive results, and even more pushed national movements to fight for exit from USSR . The weakening of the union was facilitated by the growing economic crisis. M. Gorbachev and the central government, clearly unable to cope with the task of overcoming the economic recession and reforming the economy, were losing their authority among the people every year...

4399 Words | 18 Page

Carrying out industrialization in the USSR

5 5 2. Industrialization plan in USSR 11 3. Achievements and costs of the industrial leap 16 Conclusion 18 References 20 INTRODUCTION Socialist industrialization USSR - process of accelerated expansion of industrial potential USSR to reduce the gap between the economy and developed capitalist countries, carried out in the 1930s. The official goal of industrialization was to transform USSR from a predominantly agricultural country...

Trade unions are associations of employees created to protect their economic interests and improve working conditions. According to the composition of the united workers, they can have a narrow professional, sectoral, regional, national and even international character.

It is well known that in any market (except for a perfectly competitive market) associations of both demand and supply agents can arise. Created in order to obtain economic advantages and benefits for their members, these associations give rise to certain restrictions on freedom of competition with all the ensuing consequences in the field of pricing.

In the labor market, hired workers do not always occupy an equal position in relation to employers that corresponds to fair economic relations. After all, on the employer’s side there are advantages such as wealth, organizational capabilities of the enterprise, and often political influence. In this regard, hired workers have a natural need to oppose the buyers of labor with the combined power of its sellers.

Trade unions should play the role of such a force. Their main task is to protect employees from possible exploitation by enterprises that demand labor and pay it at a low price. Therefore, trade unions organize collective forms of labor sales instead of individual ones. They are trying to ensure an increase in wages, an increase in the number of employees, improved working conditions for workers and social guarantees for the unemployed. Along with carrying out purely economic tasks, trade unions often interfere in the political life of their countries. Significant politicization is characteristic, in particular, of European trade unions.

Trade unions in the USSR and Russia

In pre-revolutionary Russia, the trade union movement, suppressed by the monarchical state, was unable to reach the required degree of maturity. Its real impact on labor relations was virtually non-existent. Later, under Soviet rule, trade unions functioned as part of the party-state mechanism. They did not interfere at all in many issues that traditionally formed the core of trade union activity. Thus, they did not even try to achieve higher wages and did not go on strike.

Being dependent on the country's leadership, Soviet trade unions nevertheless played an important role in solving numerous social problems. Without the consent of the trade union committee it was impossible to fire a single employee. Through the trade union system, various preferential (not sold at full price) vouchers to sanatoriums, rest homes, etc., travel tickets were distributed, and financial assistance was provided to those in need.

Currently, Russian trade unions are taking only the first steps towards establishing fundamentally new relationships with both the state and enterprises. They have yet to take an independent place both in the emerging market system as a whole and in the labor market. The largest association of trade unions - the Federation of Independent Trade Unions of Russia (FNPR) - is the direct "successor" of the Soviet trade unions and unites the majority of workers in state and privatized enterprises. There are still large elements of formalism and bureaucracy in the activities of the FNPR, and the ability to actually defend the interests of workers (for example, to achieve payment of wage arrears at a particular company) is limited. As for new private firms, there are usually no trade union organizations at all. Nevertheless, modern Russian trade unions (especially at the local level) have ceased to be obedient appendages of the state. Their organization of strikes and mass protests are the first signs of the independent role of the trade union movement in the economy.

There are three main models for the functioning of the labor market with the participation of trade unions.

Model for stimulating labor demand

The first model is focused on increasing wages and employment by increasing the demand for labor. A trade union can achieve such an increase by improving the quality of labor goods (for example, by promoting an increase in labor productivity at the enterprise or increasing demand for finished products).

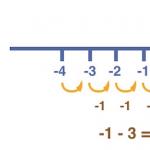

Let's present this model graphically (Fig. 11.11).

Rice. 11.11.

When the union achieves an increase in the demand for labor, the demand curve shifts to the right from position to position . In this case, two most important tasks of trade unions are simultaneously solved: employment increases (from to ) and the wage rate increases (from to ). It is obvious that the considered model is extremely attractive, but in practice it is difficult to implement. In fact, trade unions in this case act in the interests of both their members and entrepreneurs, since they improve the quality of the labor resource. This is possible only in conditions of social peace and partnership in society. Japanese workers provide an example in this regard. In accordance with the established relations between labor and capital in the country, they do a lot for the prosperity of their companies free of charge and voluntarily. For example, they organize quality circles in which, after work, problems of improving products are discussed.

Labor Supply Reduction Model

The second model is focused on increasing wages by reducing labor supply. This reduction can be achieved within the framework of narrowly professional (shop) trade unions, which are usually called closed or closed. Such trade unions establish strict control over the supply of highly qualified labor by limiting the number of their members, for which they use long training periods for the relevant profession, restrictions on the issuance of qualification licenses, high entry fees, etc.

At the same time, trade unions seek to pursue policies aimed at reducing the overall supply of labor, in particular by seeking, in particular, the adoption by the state of relevant laws (for example, establishing mandatory retirement at a certain age, limiting immigration or reducing the length of the working week).

A graphical representation of this model is shown in Fig. 11.12.

Rice. 11.12.

If a trade union, by one means or another, achieves a decrease in labor supply, then its curve shifts from position to position . The consequence of this will be an increase in the wage rate from to . But at the same time, employment will decrease from to .

. However, the industry trade union is seeking to set wages at a level no lower than , threatening a strike otherwise. The labor supply curve turns into a broken curve (it is thickened on the graph). In accordance with its demand curve, the enterprise will respond to an increase in the wage rate from to by reducing the number of employed workers from to.In the third (as well as in the second) model, wages increase due to a decrease in employment. From this we can conclude that the results of the struggle of trade unions for increasing wages are contradictory, since this increase itself is associated with a decrease in the number of workers. In other words, unbridled wage growth can generate unemployment.

New translations

RUSSIAN LABOR MARKET1

Simon Clarke University of Warwick, UK

Translation by M.S. Dobryakova Scientific editing - V.V. Radaev

Labor market during the Soviet period

The labor market was the only market that existed in the Soviet Union in a form that could be recognized in a capitalist economy (67, 68). Despite the intentions of the authorities to plan the distribution of labor and the insistence of almost all Soviet scientists that labor was not a commodity, in practice workers more or less freely changed jobs, and employers more or less freely hired whoever they wanted. Although wages were tightly controlled in an attempt to suppress competition in the labor market, employers in basic sectors of the economy were able to offer higher wages, housing, and a wide and increasing range of social benefits in order to attract selected workers. The least privileged industries could not compete using the same methods, i.e. offer better wages and benefits, but they could offer less intensive work hours, less strict work discipline, and more opportunities to earn extra money on the side by combining several jobs during the workday or simply by stealing public property. At the same time, wages for individual workers could be increased by assigning them higher ranks and categories or by weakening production standards. At the same time, those formal labor market institutions that ensure the process of changing jobs in developed capitalist economies did not exist. In Russia, by and large, people were forced to seek information about job vacancies through informal channels. However, before considering these informal channels, we should briefly outline the formal institutions that were supposed to regulate the movement of labor at the end of the Soviet period.

Distribution of labor force by administrative methods Entry into the labor market

Here, at the center of administrative regulation was a system of strict distribution of graduates after graduation from educational institutions. This

1 This text is a translation of part of the article Clarke, S. The Russian labor market // Aspects of social theory and modern society / Ed. A. Sogomonov, S. Kukhterin. M.: Institute of Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 1999. P. 73-88 (73-120). The translation is posted with the kind consent of the author.

The system applied primarily to graduates of higher and secondary specialized educational institutions: they were required to work in their assigned place for three years. At the same time, the authorities expected that they would remain in this workplace for the rest of their lives. The distribution of graduates to jobs was carried out by the Distribution Commission operating at the educational institution. It was based on the wishes of the student, his academic achievements and social and political activity, as well as the specific requirements of employers who addressed the management of educational institutions. The best students or those who had good connections were often assigned by their own choice - for example, to the enterprise or organization where they completed their pre-graduate internship. Others were sent to remote regions of the country, primarily to Siberia and the Far East, where labor shortages persisted. However, in practice, this system never worked fully: some students found work themselves and simply did not show up where they were assigned; others went to the distribution site and discovered that there was no work available for them there; and still others left the places of distribution without waiting for the expiration of the three-year period (67, pp. 46-47). Since the 1980s the distribution system also extended to graduates of vocational schools. As a rule, these students were sent to the enterprise to which their vocational school was attached, although in practice, many found work here themselves. Local youth distribution commissions were supposed to find jobs for school leavers, but their effectiveness was highly controversial (68, p. 110).

Administrative distribution in the next stages

Although the country had a clear career ladder, in which personal connections played an important role, as well as professional and political qualities, its top positions were also filled through administrative means. The appointment of people to senior positions in all spheres of economic, social and political life was regulated by a nomenklatura system, under which party committees at all levels approved a list of persons eligible for promotion. From this list, candidates were selected when a vacant position arose (73). In principle, any party member could be ordered, in the interests of the party state, to move to another job, for example to travel to a remote region, which was common in the 1930s, but such a practice became quite rare in the post-Stalin period.

Other administrative methods of assigning people to jobs were based on material incentives and did not include a coercive component, so they should be considered market rather than administrative mechanisms (67, pp. 45-53). The organizational set arose in the early 1930s. on the initiative of industrial enterprises that entered into agreements with collective farms on the supply of labor. Gradually, organizational recruitment was systemized and bureaucratized, and it soon became the main channel for recruiting the rural population to work in industry and construction at a time when villagers did not have the right to leave their place of residence. Since the 1950s. organizational recruitment was used primarily to attract labor to the developing regions of Siberia and the Far East. In this case, a contract was concluded with a specific employer for a period of one to five years (average duration - 2 years), he was allocated lifting costs and paid transportation costs. In the 1980s organizational recruitment covered 20% of the planned recruitment of workers for Siberia and the Far East, while almost a third went through the line

Ministry of Energy, while its share in the industry as a whole was not so large. Since no additional funds were allocated for family members in this case, most people hired in this way were single, and about two thirds of them were under 29 years of age. The same problems arose with organizational recruitment as with the distribution of graduates: many discovered that living and working conditions did not correspond to those promised; or people simply turned out to be unnecessary and left before the contract expired. There were also complaints that the organizational recruitment attracted far from the best workers, but only fliers, jumping from place to place in the hope of lifting and covering transportation costs (67, pp. 51-52). Schemes for resettling people in rural areas were smaller in scale, but they provided for more substantial payments and allowed entire families to move (68, pp. 112-113).

Komsomol calls were initially introduced by N.S. Khrushchev with the aim of developing virgin lands; subsequently they were increasingly used to attract labor for large construction projects in the country. Although the terms of the contracts were more flexible than in the case of organizational recruitment, and the ideological load was much stronger, the material conditions were similar, and, as it turned out, people mobilized at the call of the Komsomol were not particularly eager to remain at their place of work after the end of the contract. Most students entered into short-term contracts, mainly to work on construction sites or in agriculture, primarily during the holidays.

Finally, it is important not to forget the important role that forced labor played throughout the Soviet era. Although mass repressions ended with the death of I.V. Stalin, a very large number of people were sentenced to certain terms of imprisonment in forced labor colonies. However, subsequently they were often charged with forced settlement in regions where there was a labor shortage. In addition, large numbers of military conscripts and military personnel were widely used to work on civilian projects or to fill seasonal labor needs, such as harvesting crops or clearing streets of debris at the end of winter.

Labor mobility

According to the Soviet ideal, each individual was to be given a job according to his qualifications and the needs of the economy. It was assumed that he would subsequently make a career at the enterprise or organization to which he was sent, and appointment to senior positions would be controlled by the nomenklatura system. The reason for such a persistent desire to consolidate the structure of employment was not so much the attempt of planning authorities to control the distribution of labor (in practice, they could achieve this through market mechanisms), but rather the central role assigned to the workplace in the process of maintaining order and stability of Soviet society.

The workplace was the main element of social integration within the Soviet system. And the party’s policy was aimed at securing people in their jobs: this made it easier to regulate and control their lives. At the same time, this ideal was carried out in practice, first of all, by providing enterprises with significant social benefits and privileges for length of service. The main place of work was not only a source of livelihood, but also an indicator of social status. Lack of work

condemned not only to material deprivation, but also to the risk of being imprisoned on charges of “parasitism.” The authorities did not encourage dismissal of even the most undisciplined workers as a means of control over the workforce, because those fired had to be sent to some other place of work. So the number of disciplinary dismissals was extremely small, although the management of the enterprise could force those who violated discipline to leave of their own free will.

This policy was also reflected in the subjective orientation of workers, which was based on the ideal: work for life, and the workplace as a “second home.” The ideal work path for a Soviet worker was to find a suitable job and then remain there for the rest of his/her working life, making a career by moving from one position to another within the enterprise itself. If, however, there was a need to change jobs, this was done through a transfer agreed upon with the management of the enterprises and/or external organizations. Such a transfer allowed the employee to maintain continuous work experience and associated social benefits.

In practice, however, this did not work as intended because there was no effective mechanism to keep people in their jobs, with businesses and organizations always competing with each other for labor. Workers, especially in the early stages of their careers, sought better pay and working conditions, better prospects for housing and child care (67, pp. 280-282). As a result, the level of labor mobility was quite high. Thus, most of the hiring of workers took place outside of any administrative distribution of labor, but was carried out directly between the individual and the future employer. Moreover, approximately two-thirds were direct transfers from one job to another (67, p. 276).

There is very little data on staff turnover and the channels through which people found work in the Soviet system, since such information was considered a state secret and was not subject to publication until the end of the Soviet period. And the available data (primarily the data from research reports) are completely inconsistent with each other (for this kind of data, see 67, Chapter VI). As A. Kotlyar writes, 14.2% of the total number of employed in Russia in 1980 were graduates of educational institutions, 2.8% were young people, 3.8% were transferred, 0.9% were involved in organizational recruitment and resettlement of rural families, 0.5% - at the call of the Komsomol, and 77.8% were direct hiring of workers by enterprises (67, p. 269; 68, pp. 109-113; 61, p. 62).

This small proportion of administrative methods of assigning workers is the result of high labor turnover, which meant that the majority of all hires were people who moved at their own discretion from one job to another. Overall level of labor mobility in the Soviet Union since the 1960s. was comparable to those for capitalist labor markets: turnover was approximately 20% per year and fell to approximately 15% in the mid-1980s. These figures are similar to those for many European countries; they are higher than in Japan and significantly lower than in the United States2. However, the Soviet reverent attitude towards high

2 Official data show that since the mid-1970s. significant

The level of labor mobility becomes quite understandable if we place it in the context of employment dynamics, on the one hand, and social norms, on the other. The “extensive” path assumed a rigid employment structure; jobs were eliminated extremely rarely, since the creation of new industries was not accompanied by the liquidation of old production capacities. Thus, very few people were forced to leave their jobs as a result of retrenchment, and even fewer as a result of disciplinary dismissals. Likewise, centralized determination of wage levels did not put pressure on workers in depressed industries by reducing the relative level of this wage. On the other hand, strong social norms supported employment stability. A high level of labor mobility was characteristic, as a rule, primarily of young workers who were looking for a more suitable place of work, as well as the least socialized and least disciplined workers, who also usually had lower qualifications. However, persistent labor shortages meant unemployment was low, and those who left their jobs were confident that they would find another job as soon as they chose. Despite the curbs on labor mobility, workers had sufficient freedom to change jobs in accordance with their own interests and preferences.

Personnel turnover was viewed by the Soviet authorities not only from the point of view of negative social consequences, but also as a serious economic problem and a waste of resources. Workers left the jobs for which they were trained and went to new jobs, where they again needed time to prepare. At the same time, the break between work at the old and new places was approximately one month (67, p. 306316). Accordingly, there have been quite a lot of studies devoted to the reasons for high employee turnover. The objective of these studies was to identify ways to improve the system of wages and bonuses, as well as change working conditions that would reduce labor mobility. Ideas about labor mobility as a positive phenomenon were also absent among economists, who did not consider it as a means of increasing labor productivity, achieved by better matching the worker with his place of work. They are also absent among workers who could not consider it as a means of constructing a fulfilling working life. Consequently, labor market institutions such as those found in the West were very underdeveloped, and labor mobility was never explored as a tool for economic restructuring or as an element of workers' employment strategies.

reduction in the labor turnover rate (it subsequently began to rise from 11% of industrial workers in 1986 to 13% in 1989 (26, p. 126) and to approximately 30% in 1992). Soviet commentators explained such a sharp drop in the turnover rate in the first half of the 1980s. successful implementation of a number of measures to improve labor discipline and reduce turnover, which followed the official announcement in December 1979. Western commentators were more skeptical about the effectiveness of these measures, which included, for example, the following: the consideration of applications for resignation was extended by 2-4 weeks. Partly due to the decline in turnover rates in the mid-1980s. can be explained by the aging of the workforce (68, p. 217), as well as, probably, by Yu.V. Andropov’s short campaign to tighten labor discipline (67, p. 315; 61, p. 63).

In practice, the central authorities sought to regulate the labor market through market rather than administrative mechanisms. Higher wages were paid to workers in remote regions where labor was scarce and in basic industries where greater social benefits were also offered. This gave the basic industries, and above all the military-industrial complex, a great advantage in the labor market, which made it possible to attract the best workers and have a stable workforce. The flip side of this situation was that lower-priority sectors, including services, light industry and construction, experienced greater difficulty in attracting labor and higher turnover (68, p. 217; 62). Changes in social policy that occurred from the mid-1980s were aimed at securing the worker in the enterprise, providing him with housing and providing a wider range of social benefits and benefits tied to a given workplace. However, as a result, wealthier enterprises received more advantageous positions in the labor market. Survey data showed huge differences in turnover rates among different enterprises in the same industry, thereby reflecting the extent of competition between enterprises in the labor market. Higher turnover was also found in large cities, in smaller enterprises, and among younger and lower-paid workers (67, pp. 275-276).

Intermediaries in the labor market

Despite the fact that most of all hiring of workers was done without administrative control, during almost the entire Soviet period there were formal intermediaries in the labor market, engaged, in particular, in the placement of youth and such special categories as disabled people demobilized from the army and released from prison. places of detention. Only in 1969, in order to improve the efficiency of the labor market, labor exchanges were re-established (in 1930 they were abolished due to the official announcement of the elimination of unemployment). In the period between these two events, the company was fully responsible for the employment of dismissed workers, as well as for the payment of compensation for two weeks after dismissal. By 1970, 134 employment bureaus had been established, and by 1989, 812 employment centers and 2,000 employment bureaus had emerged throughout the Soviet Union. However, for a number of reasons, such bureaus turned out to be ineffective. First, ironically, unlike most capitalist countries, these institutions did not receive government support, but had to finance their activities through deductions from enterprises, which led to underfunding and problems with personnel (67, pp. 24, 406 -407). Second, many businesses did not report their vacancies, and most of the reported jobs were for low-skilled workers. Third, these bureaus had a very low reputation and were the last resort of people who despaired of finding work on their own, and businesses that could not fill empty jobs. However, according to their own reports, these bureaus soon began to play a decisive role in the process of labor distribution, accounting for more than 20% of all hiring in Russia in 1981. They significantly reduced the time gap in moving from one job to another, ensuring in 1973, 87% of those who wanted information about jobs were provided with information and 59% actually found jobs (68, pp. 115-116). According to our own data, these bureaus and their successors, as we will see below, played a much larger role in the labor market.

less significant role. Labor market policy

Throughout Soviet times, labor market policy was subordinated to the primary task of mobilizing labor reserves for the needs of building Soviet industry. In the 1930s it was necessary to relocate, largely by force, a large proportion of the rural population to new centers of processing and mining industries. After Stalin's death, the emphasis gradually shifted to the use of material incentives to attract the rural population into industry and construction, but by the end of the 1950s. It had already become clear that the influx of workers (including women) from agriculture, which played an auxiliary role, into the army of hired labor, as well as the natural increase in the urban population, was not enough to satisfy the insatiable demand of the Soviet system for labor. During the 1960s and 1970s. The attraction of the non-working population, consisting primarily of pensioners and women with children, played an increasingly important role. Restrictions on the employment of pensioners were gradually relaxed, and by the end of the Soviet period, pensioners could receive a full pension even if they continued to work, subject to a certain “ceiling” of maximum total income3. Likewise, childcare benefits have become widespread and women have gained new rights regarding maternity leave. All these measures had a noticeable impact on attracting these two categories of workers into the labor force (67, pp. 106-107, 218-225). At the same time, they contradicted the goals of social and demographic policy, which especially concerned the employment of women with children. A dramatic illustration of the state of affairs was the high level of infant mortality and the sharp decline in the birth rate.

Since the 1980s. Soviet specialists switched attention from the labor shortage on the external labor market to the surplus of labor employed in existing enterprises. This led to debate about the extent to which Soviet enterprises fed large domestic reserves of labor that could be mobilized to meet the demands of ongoing economic growth (this debate is discussed in detail in ). The theoretical problem was the apparent coexistence of labor shortages at the macro level and labor surpluses at the micro level. The phenomenon of "overemployment" was explained by the shortcomings of the planning system, which gave enterprises an incentive to maximize the workforce and which required them to hold back a significant part of the workforce as a reserve in case of changing needs4. The reason was also seen in the imperfection of the strategy

3 Pensioners in Russia can be quite young. It's not just that pension

The age here is five years lower than in most countries (55 years for women and 60 for men), but also in the fact that many workers have the right to early retirement due to harmful or difficult working conditions. An underground miner, for example, can retire after 20 years of service. These “privileges” are balanced by low life expectancy, especially for men, and the widespread incidence of accidents and illnesses at work.

4 Such needs included the right of local authorities to call upon a significant proportion of the workforce

forces from local enterprises to meet any short-term needs. They widely used this right, especially in the case of harvesting, construction, and also

capital investment, where the emphasis on primary production has led to an extremely low level of mechanization of auxiliary labor; as well as in the incompetence of managers, which led to ineffective use of labor within the enterprise.

Attempts were made to eradicate the shortcomings of the planning system through a series of "experiments" carried out starting in the mid-1960s. It was proposed to give enterprises and organizations an incentive to reduce the number of employees by retaining for them the funds saved as a result of increasing labor productivity. As is the case with all other Soviet “campaigns,” such experiments gave good results at advanced enterprises in the short term, however, due to system failures, it was not possible to maintain a significant impact of the experiments in the long term (1; 68, pp. 169-81 ; 67, pp. 161-71). There was an underlying tension between the integrity of the administrative-command system, which required the center to maintain control over the distribution of resources, and the need to encourage initiative in the acquisition and management of resources.

By the mid-1980s. It became generally known that the Soviet economy had a surplus of 10-15% of the labor force, but the sources of such data were never cited (67, p. 154). Since the view that labor shortages were a Soviet invention and that labor shortages were an integral feature of Soviet enterprises has become common among post-Soviet analysts, it is important to clarify what is meant by these internal surpluses. Survey data consistently showed that the vast majority of enterprises faced labor shortages, and this proved to be a significant obstacle to achieving the plan. On the other hand, survey data also showed that after implementing systemic reforms - such as changing the planning system, improving the management system and improving the reliability of supplies - many enterprises could meet production targets using much less labor. A more rational investment program, including the dismantling of outdated factories and the mechanization of auxiliary and auxiliary labor, would save even more labor (68, pp. 19-20, 151160). Thus, there is no evidence that there was a significant surplus of labor in the sense that enterprises and organizations accumulated labor reserves that could be freed up without any effort for more efficient use. This is true only in the sense that there was an extremely wide range of ways to increase labor productivity through management reform and more rational capital investment programs (see 8, 52). This served as the basis for a series of reforms during the era of perestroika, the essence of which was the release of internal labor reserves based on an increasingly radical transformation of the administrative-command system. The result of these attempts was the rapid disintegration of the system, when the center lost control over the distribution of resources, which had previously formed the basis

repair of municipal buildings and roads. According to published data, during the 1980s. in the Soviet Union, such tasks absorbed 700-800,000 man-years per year (68, p. 113). This figure, however, is clearly a significant underestimate, since a significant part of this kind of labor mobilization was carried out informally and, therefore, was not officially registered.

his power over enterprises and organizations (12). The impact of perestroika on the Soviet labor market

This work does not imply coverage of all the turns and leaps of perestroika; it only touches on its impact on the Soviet labor market (68, chapters 9 and 10; 67, chapter VIII). The fundamental elements of the reform program from the point of view of labor market development were the wage reform of 1986 and the Self-Employment Act, which was combined with a renewed fight against unearned income; Public Enterprise Act 1987; Cooperatives Act 1988 and Tenancy Act 1989; finally, the expansion of the activities of the Employment Bureau and the introduction of unemployment benefits in 1988.

The main goal of the wage reform was a closer link between wages and labor productivity, increasing the independence of enterprises and institutions in setting the level of wages and its differentiation depending on the dynamics of labor productivity, with a subsequent reduction in the workforce (21). The reform was first introduced on a pilot basis on the Belarusian railway in 1985-86, where it had a decisive impact on wages, employment and productivity - and was eventually extended throughout the Soviet railway system5. The widespread implementation of wage reform required radical changes in the relationship between enterprises and the ministries above them - changes that would give enterprises greater independence in determining the number of employees and disposing of their own income. These changes occurred in 1987, when the State Enterprise Law was adopted.

It was expected that the reforms would lead to massive layoffs, but it was assumed that the subsequent regrouping of the workforce would help avoid unemployment, which continued to be considered an unacceptable phenomenon throughout the entire period of perestroika. In order to facilitate the employment of the displaced workforce, in 1988 the Employment Bureau was given significant powers. Enterprises and organizations were now obliged to inform them about all their vacancies, as well as upcoming layoffs (the sanctions, however, were insignificant). Central services received new rights to coordinate staff retraining (although the costs had to be covered by the new employer), as well as provide advice on choosing a profession. The entitlement to redundant workers' benefits (paid by the employer) has been increased from the previous two weeks' salary to two months' salary. At the same time, those who registered with the employment center within two weeks from the date of layoffs continued to receive monthly benefits. The powers of the Employment Bureau were further expanded by the Employment Law of 1991, which for the first time recognized the existence of unemployment and established the Federal Employment Service, financed by mandatory

5 These improvements had little to do with wage reform. A third of all job cuts in Belarus were attributed to additional capital investment, more than half to labor intensification through revised standards and employment reductions, and one-eighth to management rationalization. One-fifth of those who lost their jobs were re-employed in the railroad system, 40% retired, and 40% found work in other industries (67, p. 395).

deductions linked to the wage fund of enterprises. According to the new Law, unemployment benefits were to be paid through employment services; it was in addition to the redundancy compensation that the enterprise provided under the previous law. The law provided employment services with a wide range of new opportunities, including training and retraining, financing the maintenance and creation of jobs, and public works.

There has been much debate regarding the role that wage reform has played. Everyone, however, agrees that she did not live up to the expectations placed on her. According to Soviet experts, 2.3 million jobs were eliminated by July 1988 due to this reform. However, 13% of such cases are explained by the elimination of unfilled vacancies, 35% are the movement of personnel to vacant positions within an enterprise or organization, 1 7% are the retirement of workers who have reached retirement age, and the remaining third, or 800 thousand workers, i.e. . less than 1% of the workforce looked for work elsewhere. In other words, the wage reform explained, at best, only 10% of the total turnover in the year of its implementation (68, p. 252).

In fact, it turned out that legislation on new forms of labor activity had a much greater impact than the wage reform or the Law on State Enterprise. Individual labor activity has always existed legally in the form of peasant subsidiary farming and illegally in the form of providing a wide range of services to the population. By the 1980s subcontracting work carried out by independent teams of workers (shabashniks) has become widespread, primarily in the field of construction in rural regions (68, pp. 113114; 67, pp. 363-374). Self-employment, cooperative, and tenancy laws not only provided individuals with the ability to legally sell the products of their individual or collective labor, but more importantly, they provided businesses and organizations with a loophole through which they could escape centralized controls over wages and employment by concluding agreements with formally independent cooperatives and rental enterprises, as well as avoiding control over their financial activities by establishing formally independent “pocket banks”. It was these reforms that broke the system of administrative control over wages and employment and acted as a stimulating factor in the significant increase in staff turnover in the late 1980s.

The immediate impact of perestroika on the Soviet labor market was relatively limited. A number of changes took place in the legal or administrative sphere regarding the distribution and re-absorption of labor. There were no significant changes in the structure of the labor force. There was a subtle tendency to redistribute labor from the sphere of material production to the service sector. There was a more significant increase in staff turnover, which was probably more a consequence of new opportunities in the nascent private sector than the impact of wage reform or the greater independence granted to state-owned enterprises. The role of the Labor Employment Bureau increased, employment growth began to be controlled, but the unemployment rate did not increase significantly, since reductions in production were compensated by the departure of some pensioners from the labor market. However, the erosion and then the collapse of the administrative-command system, which forced a rapid transition to a market economy, led to significant changes in the structure

wages and employment, resulting in increased levels of labor mobility as workers responded to changing market conditions.

Literature

1. Arnot, B. Controlling Soviet Labor. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988.

2. Ashwin, S. The Anatomy of Patience. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999.

3. Brainerd, E. Winners and Losers in Russia's Economic Transition. American

4. Economic Review 88, 1998. Pp. 1094-116.

5. Brown, A.N. The Economic Determinants of Internal Migration Flows in Russia During Transition, 1997, cited in Grogan, 1997.

6. Brown, W., Marginson, P. and Walsh, J. Management: Pay Determination and Collective Bargaining in Edwards, P.K. (ed.) Industrial Relations: theory and practice in Britain. Oxford: Blackwell Business, 1995.

7. Brown, W. and Nolan, P. Wages and Labor Productivity: The Contribution of Industrial Relations Research to the Understanding of Pay Determination. British Journal of Industrial Relations 26, 1988. Pp. 339-61.

8. Clarke, S. Labor Relations in Transition. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 1996b.

9. Clarke, S. Structural Adjustment without Mass Unemployment. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 1998a.

10. Clarke, S. and Kabalina, V. The New Private Sector in the Russian Labor Market. Europe-Asia Studies 52, 1, 2000.

11. Clarke, S. and Metalina, T. Training in the New Private Sector in Russia. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 2000.

12. Clarke, S., Borisov, V. and Fairbrother, P. “The Workers" Movement in Russia. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 1995.

13. Clarke, S., Fairbrother, P., Burawoy, M. and Krotov, P. What about the Workers? Workers and the Transition to Capitalism in Russia. London: Verso, 1993.

14. Commander, S., Tolstopiatenko, A. and Yemtsov, R. Channels of Redistribution: Inequality and Poverty in the Russian Federation. Inequality and Poverty in Transition Economies. London: EBRD, 1997.

15. Commander, S., Dhar, S. and Yemtsov, R. How Russian Firms Make Their Wage and Employment Decisions in Commander, S., Fan, Q. and Schaffer, M.E. (eds.) Enterprise Restructuring and Economic Policy in Russia. Washington D.C.: The World Bank, 1996.

16. Commander, S., McHale, J. and Yemtsov, R. Russia in Commander, S. and Coricelli, F. (eds.) Unemployment, Restructuring and the Labor Market in Eastern Europe and Russia. Washington DC: The World Bank, (1995).

17. Davis, S.J. andHaltiwanger, J. Wage Dispersion Between and Within US Manufacturing Plants, 1963-86. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Microeconomics, 1991. Pp. 11580.

18. Doeringer, P.B. and Piore, M.J. Internal Labor Markets and Manpower Analysis. Lexington: Heath, 1971.

19. Donova, I. Wage systems in pioneers of privatization in Clarke, S. (ed.) Labor in Transition: Wages, Employment and Labor Relations in Russian Industrial Enterprises. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 1996.

20. Earle, J. and Sabirianova, K. Understanding Wage Arrears in Russia, SITE Working Paper No. 139, Stockholm School of Economics, 1999.

21. Fevre, R "Informal Practices, Flexible Firms and Private Labor Markets". Sociology 23, 1989. Pp. 91-109.

22. Filtzer, D. Soviet Workers and Perestroika. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

23. Gaddy, C. and Ickes, B. Russia's Virtual Economy. Foreign Affairs 77, 1998. Pp. 53-67.

24. Gerber, T.P. and Hout, M. More Shock than Therapy: Market Transition, Employment and Income in Russia, 1991-1995. American Journal of Sociology 104, 1998.

25. Gimpel'son, V. and Lippoldt, D. Labor Turnover in Russia: Evidence from the Administrative Reporting of Enterprises in Four Regions Transition Economics Series No. 4. Vienna: Institute for Advanced Studies, 1999.

26. Goskomstat RSFSR (1990). Narodnoe khozyaistvo RSFSR v 1989 g. Moscow: Respublikanskii informatsionno-izdatel"skii tsentr.

27. Goskomstat Trud i zanyatost" v Rossii. Moscow: Goskomstat Rossii, 1995 p.

28. Goskomstat "O differentsiyatsii zarabotnoi platy rabotayushchikh na predpriyatiyakh (organizatsiyakh) v 1 polugodii 1996 year". Information statisticheskii byuulleten" 13, 1996b. Pp.65-82.

29. Goskomstat "Rynok labor Rossiiskoi federatsii v 1996 godu". Information statisticheskii byuulleten" 13, 1996d. Pp. 45-64.

30. Goskomstat "Organizatsiya obsledovanii naseleniya po problemam zanyatosti (obsledovanii rabochei sily) v rossiiskoi federatsii." Voprosy statistiki 5, 1997a. pp. 27-38.

31. Goskomstat "O raspredelenii rabotayushchikh po razmeram zarabotnoi platy v 1997 godu". Statisticheskii byulleten" 2(41): (1998b). 70-96.

32. Goskomstat "O zanyatosti naseleniya". Statisticheskii byulleten" 9(48), 1998 pp. 59-156.

33. Goskomstat Rossiiskii Statisticheskii Ezhegodnik. Moscow: Goskomstat Rossii, 1998 e.

34. Goskomstat "O zanyatosti naseleniya". Statisticheskii byulleten" 3(53), 1999a. Pp. 5-141.

35. Goskomstat Russia v Tsifrakh. Moscow: Goskomstat Rossii., 1999b.

36. Goskomstat Sotsialnoe polozhenie i uroven" zhizni naseleniya Rossii 1998. Moscow: Goskomstat Rossii. (1999c).

37. Granovetter, M. The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology 78 (May), 1973. Pp. 1360-80.

39. Grimshaw, D. and Rubery, J. Integrating the internal and external labor markets. Cambridge Journal of Economics 22, 1998. Pp. 199-220.

40. Grogan, L. Wage Dispersion in Russia. Amsterdam: Tinbergen Institute, mimeo, 1997.

41. Groshen, E.L. Sources of Intra-Industry Wage Dispersion: How Much for Employers

Matter?. Quarterly Journal of Economics 106, 1991. Pp. 869-84.

42. Gudkov, L.D. Kharakteristiki respondentov, otkazyvayushchikhsya or kontaktov with intervyuerami. VTsIOM: Economic i sotsial "nye peremeny: monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: 45-8, 1996.

43. Healey, N.N., Leksin, V. and Svetov, A. Privatization and enterprise-owned social assets. Russian Economic Barometer 2, 1998. Pp. 18-38.

44. Ickes, B. and Ryterman, R. From Enterprise to Firm: Notes for a Theory of the Enterprise in Transition in Grossman, G. (ed.) The Post-Communist Economic Transformation. Boulder: Westview Press, 1994.

45. Ilyin, V. “Social contradictions and conflicts in Russian state enterprises in the transition period” in Clarke, S. (ed.) Conflict and Change in the Russian Industrial Enterprise. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 1996.

46. IMF/World Bank/OECD "A Study of the Soviet Economy, 3 volumes", 1991.

47. Jenkins, R., Bryman, A., Ford, J., Keil, T. and Beardsworth, A. Information in the Labor Market: the Impact of Recession. Sociology 17, 1983. Pp. 260-7.

48. Jenkins, S.P. Accounting for Inequality Trends: Decomposition Analyzes for the UK, 1971-86. Economica 62, 1995. pp. 29-63.

49. Kabalina, V. and Ryzhykova, Z. Statistika i praktika nepolnoi zanyatost" v Rossii (Short-time Working in Russia). Voprosy ekonomiki 2, 1998. Pp. 131-43.

50. Kapelyushnikov, R. Job Turnover in a Transitional Economy. Labor Market Dynamics in the Russian Federation. Paris: OECD/CEET, 1997.

51. Kapelyushnikov, R. Job Turnover in a Transitional Economy. Labor Market Dynamics in the Russian Federation. Paris: OECD/CEET, 1997.

52. Kapelyushnikov, R. Overemployment in Russian Industry: Roots of the Problem and Lines of Attack. Studies on Russian Economic Development 9, 1998. Pp. 596-609.

53. Kapelyushnikov, R. Rossiiskii rynok truda: adaptatsiya bez restrukturizatsii. Moscow: IMEMO, 1999.

54. Korovkin, A.G. and Parbuzin, K.V. Evaluation of Structural Unemployment in Russia. Russian Economic Barometer 2, 1998. Pp. 13-17.

55. Kotlyar, A. Sistema trudoustroistva v SSSR. Economic sciences 3, 1984.

56. Kruger, A.B. and Summers, L.H. Efficiency Wages and the Inter-Industry Wage Structure. Econometrica 56, 1988. Pp. 259-93.

57. Layard, R., Nickell, S. and Jackman, R. Unemployment: Macroeconomic Performance and the Labor Market. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

58. Leontaridi, M.R. Segmented Labor Markets: Theory and Evidence. Journal of Economic Surveys 12, 1998. Pp. 63-101.

59. Linz, S.J. Russian Labor Market in Transition. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 1995. Pp. 693-716.

60. Magun, V. Rossiiskie trudovye tsennosti: ideologiya i massovoe soznanie. Mir Rossii 4, 1998. Pp. 113-44.

Home > DocumentEffective employment policy in the USSR.

The labor market in post-revolutionary Russia.

Labor market under the NEP.