Russia in the 16th century developed towards an estate-representative monarchy. Estates-representative monarchy- this is a type of power when the monarch rules the country, relying primarily on class-representative institutions that exist in the vertical of central power. These representative institutions express the interests of all free classes of society.

A number of domestic historians believe that an estate-representative monarchy in Russia began to take shape already in the 15th century. during the period of completion of the political process of unification of Rus'. Then, under the sovereign of all Rus' Ivan III, the Boyar Duma acted as a permanent advisory body in the system of supreme power.

The Boyar Duma represented and expressed the interests of large landowners, many of whom had recently been great or appanage princes, but gradually during the formation single state turned into subjects of the great Moscow princes and sovereigns. The Boyar Duma under Ivan III and Vasily III performed two functions. Firstly, it provided support for the power of a single monarch - the sovereign of all Rus'. Secondly, it contributed to overcoming still remaining elements and trends feudal fragmentation and separatism.

In Russia in the middle of the 16th century. Along with the Boyar Duma, a new political structure began to operate in the system of public administration - Zemsky Sobors, or “councils of the whole earth,” as their contemporaries called them.

The appearance of Zemsky Sobors in the system of political power was not an accidental or temporary phenomenon. It became the call of the times along with the reforms of the mid-16th century, which were energetically carried out by the Middle Duma, or Elected Rada with the direct participation of Ivan IV.

Political development Russia in the 16th century it was going contradictory. The unification of Russian lands within a single state did not lead to the disappearance of numerous remnants of feudal fragmentation. After the death of Vasily III, a fierce struggle between boyar groups for power began under the young heir. The political actions of the warring factions (the Shuiskys, Belskys, Glinskys, etc.) differed little from each other, but greatly weakened and disorganized the system of government of the country, which was expressed in the growth of the arbitrariness of the local rulers and the dissatisfaction of the tax and service population with the boyar rule as a whole.

The beginning of the reign of young Ivan IV was marked by an aggravation of social contradictions. The muted dissatisfaction of the masses with the endless princely-boyar intrigues, infighting, local lawlessness, bribery and other abuses of officials resulted in a period popular uprisings, the most significant of which was the Moscow uprising of 1547.

During the unification of the country, the power of the Moscow sovereigns increased enormously, but did not become unlimited: the monarch could not do without the participation of the boyar aristocracy in government. Through the Boyar Duma, the nobility ruled in the center, it commanded the troops, controlled all local government (the boyars received the largest cities and counties of the country to “feed”).

Thus, in order to strengthen Russian statehood, it was necessary to speed up political centralization and rebuild the management system on a new basis with strengthening the power of the monarch. Many people in Rus' understood this. It is characteristic that among the members of the Chosen Rada was Metropolitan Macarius, a native of the lower classes (small Kostroma patrimonial landowner, rich, but not well-born) Alexey Adashev, nobleman Ivan Peresvetov - people of broad education and passionate advocates of the ideology of autocracy. For the first time in the history of Russian social thought, I.S. Peresvetov formulated the idea of the impossibility of transforming the system of government and military service in Russia without limiting the political dominance of the boyar aristocracy and involving the nobility in state affairs. The 18-year-old king passionately supported these ideas. At the Council of the Stoglavy (1551) he proposed an extensive program of reforms.

A period of transformations began, which received historical science the name “reforms of the 50s of the 16th century.” Historians will highlight 6 reforms: public administration, local government, military, judicial, tax and church.

became central public administration reform, as a result of which the following vertical of supreme power took shape in the country.

- Tsar , in whose activities the elements of autocracy became more and more clearly intensified, i.e. such a power that is ready to cooperate with representatives of all free classes, but does not consider it possible to put up with the class privileges of the boyars and princes, including the immunity of the last appanage princes.

- Zemstvo councils were convened at the will of the tsar, and therefore were not a regularly functioning body;

- they had no legal status and did not have the right of legislative initiative; their right is to discuss and make decisions on those issues that are put before the Council by the Tsar;

- Deputies-representatives were not elected to the Councils. Mostly people from local self-government were invited as representatives from the estates: heads and elected local noble and townspeople societies, zemstvo judges, provincial and townsman elders, favorite heads, kissers; from peasant communities - village elders.

- Ambassadorial order, responsible for external relations;

- Local order, was in charge of local lands, distributed them to service people, controlled local land tenure;

- Rank order, was in charge of military affairs and the appointment of command (voivodship) personnel;

- Serf order, dealt with the registration of serfs;

- The Robbery Order was in charge of the most important criminal cases throughout the state;

- Orders of the Great Treasury and the Great Parish, dealt with finances and government affairs, etc.

Boyar Duma, the status and composition of which have changed significantly. During 1547-1549 the number of Duma officials increased to 32 people, of which 18 became members of the Duma for the first time. Since the composition of the Duma was approved and determined by the tsar, there is no doubt that Ivan IV replenished it with his like-minded people. Almost all the leaders of the Chosen Rada became its members.

The social composition of the Duma has changed. If previously the Duma boyars and okolnichy sat in it with the tsar, i.e. There were two Duma ranks and only boyars received them, but now two new ranks appeared - Duma nobles and Duma clerks, which strengthened the state element of the Boyar Duma.

The Duma from an advisory body turned into an advisory-legislative body, in charge of a wide range of judicial and administrative matters. The legislative law of the Duma, according to V.O. Klyuchevsky, was first confirmed by the Code of Laws (1550), where Article 98 read: “And there will be new cases that are not written in this Code of Laws, and how those cases are carried out with the sovereign’s report and with all the boyars, and those cases in this Attribute to the Code of Law.” This did not mean that the sovereign could not decide matters or issue laws without the Duma. But, as a rule, meetings of the Duma took place in the presence of the tsar (“the tsar sitting with the boyars about business”) or by decree and authority of the tsar in his absence.

Zemsky Sobors became a new central government body with an advisory and legislative character. The most important issues of domestic and foreign policy were brought up for their consideration, on which the tsar considered it necessary to consult with the zemshchina, find agreement with it, and therefore counted on the support of the entire people.

The Councils were attended by: the Boyar Duma, the Consecrated Council (representatives of the highest clergy headed by the Metropolitan), elected representatives from service people (primarily the nobility), from the townsman “tax” population (merchants, artisans) and even from the black-growing peasantry.

With the beginning of the convening of Zemsky Sobors in Russia, an estate-representative monarchy emerged, the social base of which was the service class (nobility) and the population of cities, i.e. those social strata of society that were most interested in a strong centralized state.

At the first Council (1549), Ivan IV wanted to reconcile the representatives of the population with the regional rulers - the “feeders”. The cathedral received the name “Cathedral of Reconciliation”. Feeders openly abused power during the period of boyar rule, causing anger and discontent among service and tax-paying people. Ivan IV addressed the Council with the following words: “People of God and given to us, I pray for your faith in God and love for us: now it is impossible for us to correct your insults and ruins, I pray you, leave each other your enmities and burdens.”

We were talking about a lot of claims from the population against feeding providers. The petition hut, headed by A. Adashev, could not cope with their consideration. The tsar asked for a kind of amnesty for these claims, but was not going to forgive the insults inflicted by the governors on the local population. The Council “honestly and sternly” (according to the wording of those times) accepted the tsar’s appeal and the proposal to draw up a new Code of Law with the aim of establishing a firm order of administration and legal proceedings, limiting the power of feeders. Thus began the attack of the supreme power and zemshchina on the privileges of regional rulers - the noble princely-boyar nobility.

Zemsky Sobors operated in the country for about 100 years and had a number of features that distinguished them from representative institutions in Western Europe. It should be borne in mind that in the West there was no single principle in class representation. Researchers highlight specific features of the Russian estate-representative monarchy of the 16th-17th centuries:

IN. Klyuchevsky noted that the composition of the Councils was changeable, lacking a solid, stable organization, and therefore the Zemsky Councils did not limit the power of the tsar, being “a handout, not a concession,” “not a recognition of the people’s will as a political force, but only a merciful and temporary expansion of power to subjects who did not detract from its completeness.” For Klyuchevsky, the “inconsistency” of Zemsky Sobors in Russia in comparison with the bodies of Western European representation was obvious: “It is known what an active source of popular representation in the West was the government need for money: it forced us to convene government officials and ask them for help. But the ranks helped the treasury is not in vain, they extorted concessions" (emphasis added - Author). This was the difference between the Russian and Western European representation. The people's representatives there pulled on themselves, in Russia - on the state, and therefore at the Councils issues concerning everyone and the whole earth were resolved, and no one extorted concessions. IN. Klyuchevsky wrote: “It was as if some higher interest reigned over the entire society, over the scores and squabbles of warring social forces. This interest is the defense of the state from external enemies... Internal, domestic rivals were reconciled in view of external enemies, political and social disagreements fell silent when faced with national and religious dangers...”

Order system in the Moscow state it finally took shape by the mid-50s of the 16th century. Orders were the first functional governing bodies. They were formed gradually as needed, to solve certain administrative and managerial problems.

The most important orders of national importance were the following:

In addition to the national ones, territorial orders were created: Kazan, Tver, Little Russian (XVII century).

The bosses, or “judges” of the most important orders, were the boyars and “people of the Duma”; clerks (secretaries) and clerks (scribes) worked with them in orders. Secondary orders were controlled by nobles with clerks or clerks alone.

Thus, in the middle of the 16th century. The system of public administration at its highest, central level was significantly strengthened, a bureaucratic layer of managers became visible in it for the first time, and the role of the nobility in solving public affairs increased.

The reformers understood perfectly well that strengthening centralization was impossible without a corresponding change in the system of local government, without breaking the institution of governorship, which was fraught with separatism, ready at any moment to turn into open opposition to the sovereign power. A number of decisive measures were taken, which are generally considered to be local government reform.

It is known that since the time of Ivan III, local government in the Moscow state was in the hands of governors and volostels. Governors were placed at the head of districts, volostels governed volosts. At the disposal of the governors and volostels there was a considerable staff of servants and henchmen - tiuns, closers, praevets, and weekmen. Not being an official apparatus, they were appointed and controlled, and therefore were responsible only to their masters - governors and volosts. Both of them were interested in their position insofar as it “fed” them. “Manager,” writes V.O. Klyuchevsky, - fed at the expense of the governed in the literal sense of the word. Its contents consisted of feed and duties. Feed was contributed by entire societies within certain periods, and individuals used taxes to pay for the government acts they needed.”

Governors were appointed according to the principle of birth. They became eminent boyars, former appanage princes who became serving boyars. Many of them received control of lands in which their grandfathers and fathers had recently been complete rulers. Not only the governors and volosts with their families, but also their numerous relatives, a staff of servants, and personal guards fed at the expense of the zemstvo society. The maintenance of the viceroyal apparatus placed a heavy burden on local society.

The management of feeders was associated with endless abuses and litigation between zemstvo people and managers, which the central government was forced to deal with. A special petition hut was created, but, as mentioned above, it could not cope with the flow of complaints about the feeders.

The reorganization of local government pursued two goals: to weaken the role of the boyar aristocracy locally and to more firmly connect districts, volosts and camps with central government, subordinating them directly to Moscow.

First, these tasks found their implementation and legal codification in the new Code of Laws (1550). The limitation of the power of governors was expressed in the introduction of mandatory participation in the local court of elected representatives of local government - headmen and their assistants - kissers. The Code of Law’s article reads: “Don’t judge the court without the headman and without the kissers.”

According to the Code of Law of 1497, defenders of local interests were required to monitor the correctness of the proceedings in the local court. If they disagreed with the court's decision, they could complain (file petitions) to a higher authority - the Petition Izba in Moscow. Now they have the right to take part in the court's decision.

The results were immediate. IN. Klyuchevsky pointed out that in 1551 “the boyars, clerks and feeders made peace with all the lands in all sorts of matters”, that “the zemstvo elected judges conducted the cases entrusted to them not only without obligation (i.e. without bribes) and without red tape, but also without compensation "

In 1555, the labial reform, begun by Elena Glinskaya, was completed. Lips(districts) - larger administrative-territorial units, including several counties, were created in places where local land ownership of service people was concentrated. As a result, labial institutions spread throughout the country. Court cases concerning criminal offenses passed from governors and volosts into the hands of labial elders, chosen from the local nobility. The lip elders were directly subordinate to the Robbery Order.

In 1555-1556. Was held zemstvo reform, as a result of which the feeding system was finally eliminated. The meaning of this reform, which became widespread mainly in the black-plowed north and in parts of the central volosts, where the free “sovereign” peasantry remained, was reduced to replacing governors and volostels with bodies of zemstvo administration - zemstvo judges And zemstvo elders, favorite heads And kissers, chosen from among the townspeople and the wealthy circles of the black-growing peasantry.

The zemstvo authorities carried out trials and executions on matters of minor importance, distributed taxes (taxes) to local societies and collected them. The feeders found themselves out of work, and most importantly, they were deprived of that part of the local taxes that constituted their “fed farm-out”. These taxes now went to the royal treasury, and later to special financial orders and went primarily to support the noble army.

Judicial reform was started by updating the legislative code of 1497. Its goal, like all reforms of the 16th century, was to strengthen the central government.

The new legislative code strengthened the system of punishments, up to the death penalty, for attempts on feudal property and for speaking out against the authorities, which were qualified as “robbery of dashing people.”

The Code of Law abolished some tax benefits for monasteries, which contributed to the replenishment of the royal treasury.

Legal enslavement of the peasantry did not go any further. However, having confirmed St. George’s Day, the Code of Law increased the “payment for the elderly” and established a payment “for the cart” for the taken away peasants. The peasant's departure from the feudal lord new system payments and settlements became impossible. Every peasant who lived with the feudal lord for at least five years was declared an “old-timer” by the Code of Law, who lost the right to leave.

In order to strengthen the central control system, an important concern of the government of Ivan IV was the reorganization of the armed forces. A number of significant transformations were carried out, allowing them to be considered as military reform.

In 1550, the “Judgment on Voivodes” came into force, which limited localism in the army. From now on, strict unity of command and subordination of the governors to each other were established according to the instructions of the sovereign - “whoever is sent with whom obeys him.” New order contributed to the elimination of the traditions of feudal fragmentation in the army. A system of official subordination was introduced, discipline and combat effectiveness of the regiments increased. However, completely eliminate localism(the right to occupy a position based on nobility and length of service with the Moscow Grand Dukes, as well as seniority in the family) the tsar did not dare.

The government of Ivan IV provided some legal basis for the parochial accounts. In 1555, the “Sovereign Genealogy” was compiled, which contained information about the origin of the most noble princely and boyar families that had the rights to localism. In 1556, a new extensive document appeared - “The Sovereign's Rank”, which included records of the service of princes, boyars and nobles (a kind of service record), starting from the 70s of the 15th century. These two documents allowed the Tsar and the Boyar Duma to control and, if necessary, suppress disputes among the feudal nobility.

In 1556, simultaneously with the abolition of feedings, the “Code of Service” (the first military regulations) was issued, which precisely defined the norms for military service of all landowners. According to the Code, each feudal lord - patrimonial owner and landowner - had to bear military service by country(by origin) (see Service people) and, if necessary, field mounted warriors in full armor at the rate of one warrior for every 150 acres of land.

The shortage of soldiers or weapons was punishable by a fine. Children of boyars and nobles served from the age of 15. From this age, a nobleman went from being an undergrowth to novikom The service continued until death or injury and was inherited. The equalization in relation to the service of patrimonial owners and landowners, who equally entered the service according to the formula “horse, man and weapon,” deprived the boyars of privileges, which, in fact, turned into service people, obliged to the tsar for military service for owning the land.

However, the Moscow boyar-noble army, even in its updated form, continued to remain an armed militia that did not know any systematic training and which, having returned from a military campaign, went home.

At the same time as reforming the traditional form of the country's armed forces, the government of the Elected Rada took steps to create more regular units that would be constantly at the disposal of the supreme power. In 1550, it was decided to “place” a “selected thousand” service people in the Moscow district. A list was compiled - the “Thousandth Book”, which included 1078 people. But it was not possible to carry out the dislocation (to give estates within a radius of 60-70 versts from Moscow): the required amount of free land was not found near Moscow.

In parallel with the streamlining of service “according to the fatherland,” a new form of military service was implemented - by instrument(see Service people), i.e. according to a special set for cash and land salaries. This is how the Cossacks, city guards, gunners and archers served. Streltsy army was organized in 1550 on the basis of the squeaker detachments created under Vasily III. At first, 3 thousand people were recruited into the Streltsy army; it was consolidated into separate “orders” of 500 people. By the end of the 16th century. There were 25 thousand archers. They were in charge of the Streletsky Order.

The Streletsky army was permanent: it did not disband between campaigns, like the noble militia. However, the Streltsy army was not regular. Streltsy lived with their families in Streltsy settlements in Moscow, in the Moscow district, in major cities countries. In their free time from guard duty, the archers were engaged in crafts and trade. Already in the middle of the 16th century. Streltsy were a powerful fighting force in Russia.

By the end of the 16th century. the total number of Russian troops reached 100 thousand people, not counting 2.5 thousand hired foreigners (foreigner servicemen).

Maintaining and arming a large army required enormous funds, which in turn caused a number of changes in the tax system. Tax reform included a number of measures. The lands were newly described and a single all-Russian unit (measure) of taxation was established - big plow(see Soha). Its size depended on the quality of the land and the social (class) affiliation of its owner. In rural areas, the land tax - “per plow” - was paid by black-plowed peasants and the clergy. In the city, a “plow” included a certain number of households. According to the calculation of “soh”, duties were collected and warriors were deployed.

New taxes were introduced: “pishchalny” - for the maintenance of the Streltsy army, “polonyanechny” - for the ransom of prisoners.

The general process of centralization of power could not but affect the Orthodox Church, since it played important role in all spheres of life of society and the state. The church itself in a single state also needed stricter centralization. But for the authorities, the solution to the issue of church and monastic land ownership acquired particular importance. The solution to both looming problems of church and state was the essence church reform.

The issue of church-monastic land ownership became the subject of special consideration at a meeting of the Church Council in 1551, convened on the initiative of Ivan IV. Its decisions were compiled into 100 chapters (the collection “Stoglav”), so it received the name of the Stoglavy Council.

The government of Ivan IV intended to carry out, with the consent of the Council, the liquidation of church and monastic land ownership. These lands were needed to provide estates to service people for military service, primarily nobles - the support of the centralized state. However, the majority of the Council participants, led by Metropolitan Macarius, achieved a compromise decision:

- the right of the clergy to own real estate was recognized as inviolable;

- monastic land ownership decreased somewhat, since all princely-boyar grants to monasteries made after the death of Vasily III (1533) were annulled;

- monasteries were forbidden to buy land without the consent of the king and engage in usury, both in kind and in cash; the descendants of appanage princes were forbidden to transfer lands to monasteries “for the sake of their souls”;

- spiritual feudal lords could no longer establish new “white” settlements and courtyards in cities and had to participate in the collection of “polonian money.”

The decisions of the Council reflected the changes associated with the centralization of the state. Church rituals were unified, an all-Russian list of saints was compiled, and a number of measures were taken to strengthen the morality of the clergy.

Thus, as a result of reforms in the country, the restructuring of the central authorities was completed, a unified order system emerged that met the needs of the political centralization of the Russian state, the functions of the service order bureaucracy expanded, broad local self-government emerged, and prospects for a military and official career opened up for the middle nobility.

However, according to a number of historians, these reforms were generally of a compromise nature. On the one hand, they strengthened the state by achieving the consent of all classes, which caused an increase in the still hidden opposition on the part of the landed aristocracy, on the other hand, they strengthened the autocratic power of the tsar. “Torn apart by contradictions between the heterogeneous social elements from which it was composed, the government of compromise was not durable and fell as soon as Ivan the Terrible was faced with the question of a decisive struggle against the boyars,” notes historian A.A. Zimin. “Only during the harsh years of the oprichnina did the nobility manage to deal a decisive blow to the political prerogatives of the boyars and begin the final enslavement of the peasants.”

The historiography of the oprichnina is replete with controversial and contradictory judgments. There is also the Karamzin idea, in which the oprichnina is viewed only as a meaningless creation of a mentally ill tyrant king. This point of view was generally shared by V.O. Klyuchevsky.

Historian S.M. Soloviev approached this problem differently. Following his concept of the historical development of Russia as a process of gradual replacement of “tribal” principles with new “state” principles, he believed that the reign of Ivan the Terrible was the time of the final victory of state principles, while the oprichnina was the last decisive blow to clan relations, the bearer of which was the boyars. And therefore, despite all the cruelties, the king’s activities were a step forward.

In Soviet historiography, the main attention was paid only to the socio-economic essence of the oprichnina policy.

Modern historians also interpret the oprichnina differently. Some of them consider it not an accidental and short-term episode, but a necessary stage in the formation of autocracy, the beginning of the formation of its apparatus of power. Other historians see in the oprichnina policy the tsar’s desire to force centralization and strengthen the regime of his power, but in the absence of appropriate historical prerequisites, this task could only be accomplished through violence and terror.

At the same time, the background against which the tragedy of the oprichnina unfolded is lost sight of, namely: the presence in the country of class-representative institutions and broad local self-government. It was already noted above that class-representative institutions did not limit the power of the tsar; they remained his support. Separating the zemshchina from the oprichnina, the tsar had to be sure that she would not betray him, would not openly or covertly side with the boyars. And so it happened. The zemshchina endured, bore a heavy tax burden, defended itself from enemies and invasions, fulfilled its duty in the Livonian War, grumbled, adapted, but did not betray the tsar and thereby confirmed the historical expediency of the actions of Ivan the Terrible aimed at centralizing state power.

One can hardly agree with the interpretation of the Zemsky Councils of 1566 and 1580. as a continuation of the formal tradition of the beginning of the reign of Ivan IV, and to see in them only a demonstration of humility, an expression of almost servility on the part of the zemshchina. Firstly, Zemsky Sobors had not yet become a tradition; they were just beginning to develop their political course. Secondly, the tsar-autocrat could, in the conditions of the unfolding anti-boyar terror, not take into account the opinion of the Council. And yet he collected them. The Zemsky Sobor of 1566 decided to continue the Livonian War not only because the tsar supposedly wanted this, but also because the serving nobility did not want to lose the lands acquired during the war, and the trade and merchant leaders of the cities hoped to go with their goods through the Baltic to European markets.

Moreover, the Council of 1566, represented by several of its participants, dared to submit a petition to the Tsar, where he spoke out against the oprichnina system.

The historian R.G. most succinctly defined the meaning of the oprichnina. Skrynnikov, who views it as the result of a clash between the powerful feudal aristocracy and the rising autocratic monarchy, which relied on the nobility and the top of the trade and craft settlement, and it was on the shoulders of these classes that all local government then rested.

The historical path of tsarism to autocracy began with the oprichnina, i.e. unlimited power of the monarch. This path was started by Ivan the Terrible and completed by Peter I, who highly valued his predecessor.

The second half of the reign of Ivan IV is a bloody period in the history of the autocratic monarchy, but terror does not express the whole essence of the state-political and social structure that developed in the country in the 50s of the 16th century.

The political possibilities of an estate-representative monarchy can be judged by the totality of the issues that were resolved by Zemstvo Councils in the 16th-17th centuries, by the role of zemstvo representative institutions and the system of zemstvo self-government in overcoming the crisis of the Time of Troubles and its consequences.

At Zemsky Sobors, issues of war and peace were considered and resolved. Councils of 1566, 1580 decided on the continuation or end of the Livonian War; Cathedral 1632-1634 approved the intention of the supreme power to return the Smolensk lands, and he also put an end to the war for Smolensk with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth; The Council of 1642 spoke in favor of lifting the siege of the Turkish fortress of Azov by the Don Cossacks, who held it for five years, since Russia did not have the strength for a war with Turkey; The Council of 1653 adopted a resolution on the reunification of Ukraine with Russia and declared war on the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

New legislation was adopted at Zemsky Sobors. The Council of 1549 decided to compile the Code of Laws, and the Council of 1649 compiled an extensive, updated code - the Council Code, according to which the country lived until 1832.

At the Zemsky Councils of 1616, 1619, 1621, 1628, the financial problems of the state were resolved. At these Councils, the zemshchina agreed to new taxes and duties, to emergency collections, thereby helping to overcome the consequences of the Time of Troubles.

And, finally, the authority of the Zemsky Sobors was especially clearly manifested when it was at them that decisions were made to elect new monarchs to the throne, after the death of Fyodor Ivanovich (1584-1598) ended the Rurik dynasty on the Russian throne. The Zemsky Sobor of 1598 voted for the “installation of Boris Godunov as tsar”; The Council of 1613 approved a new dynasty - the Romanovs.

The decision of the Councils was unconditional; no one could challenge it. Otherwise, the boyars would not have started an impostor intrigue in order to remove Boris Godunov, whom they did not like, from the throne in the name of the supposedly “legitimate” heir.

Political power zemstvo self-government was obvious in the most critical moments in the history of the Russian state. It should be borne in mind that overcoming the Troubles became possible when the zemshchina realized the main impending danger of the first civil war in Russia - the loss of statehood as such. Its military self-organization is the First People's Militia, which began the national liberation struggle against the Poles and Swedes, without stopping the struggle against the boyar government in Moscow. This just cause was completed by the Second People's Militia, led by the townsman Kuzma Minin.

From the second half XVI I century The Russian political system evolved towards absolutism. Absolutism- an unlimited monarchy in which all political power belongs to one person.

The establishment of absolutism was accompanied by the gradual withering away of medieval representative institutions, which during the period of the estate-representative monarchy acted along with royal power, as well as the weakening of the role of the church in government.

Boyar Duma during the 17th century. turned from a legislative-advisory body into an advisory body under the tsar. The boyars, frightened by the scale of the class struggle, no longer opposed themselves to the autocracy, did not try to put pressure on the monarch or challenge his decisions. Under Alexei Mikhailovich (1645-1676), more than half of the Duma consisted of nobles. The king preferred to choose smart and gifted people, to promote them according to their abilities, and not just according to the nobility of their family. So, his favorite boyar, head of the Ambassadorial Prikaz A.L. Ordin-Nashchokin came from a poor family of Pskov servicemen. At meetings of the Boyar Duma, the tsar himself was often present, led the meetings, and wrote down in advance on a piece of paper issues that needed to be consulted with the Duma. After listening to advice, he made decisions on his own if he did not find agreement. But most often the Duma agreed with the tsar.

For a long time, the government relied on the support of such class-representative institutions as the Zemsky Sobors, resorting to the help of elected people from the nobility and the top of the town's society, mainly in difficult years of struggle with external enemies and in internal difficulties associated with raising money for emergency needs. Zemsky Sobors operated almost continuously during the first 10 years of the reign of Mikhail Romanov, acquiring for some time the significance of a permanent representative institution under the government. The council that elected Michael to the throne (1613) sat for almost three years. The following Councils were convened in 1616, 1619 and 1621.

After 1623 there was a long break in the activities of the Councils. The new Council was convened in connection with the need to establish emergency monetary levies from the population, as preparations were being made for the war with Poland. This Council did not disperse for three years (1632-1634). During the reign of Mikhail Fedorovich, Zemsky Sobors met several more times.

The last Zemsky Sobor met in 1653 to resolve the issue of reunifying Ukraine with Russia. After this, the government convened only meetings of individual class groups (service people, merchants, guests, etc.). However, the approval of “the whole earth” was considered necessary for the election of sovereigns. Therefore, the meeting of Moscow officials in 1682 twice replaced the Zemsky Sobor - first with the election of Peter to the throne, and then with the election of two kings - Peter and Ivan, who were to rule jointly.

Zemsky Sobors as bodies of class representation were abolished by the growing absolutism, just as it happened in the countries of Western Europe.

But the refusal of the autocratic government to support class representation when resolving fundamental issues of domestic policy was not painless for the authorities. To the decision of the government of Alexei Mikhailovich to introduce a tax on salt, collect arrears for previous years, reduce the salaries of service people “according to the instrument”, etc. without the “council of all the earth,” the people responded with massive uprisings (Salt Riot, Bread Riot, Copper Riot). This was a natural reaction of the zemshchina, accustomed to the fact that monarchs took their opinion into account. To break this zemstvo habit it was necessary to use armed forces and massacres.

The church reform and the subsequent split in Orthodox society, the establishment of the Monastic Order, which took control of the activities of the church, made the church itself completely dependent on the state, nullifying its participation in resolving state issues.

But the role of orders steadily increased, which indicated the complexity of public administration. In the 17th century their total number reached 80. The functions of the orders became extremely confusing, even intertwined with each other, which gave rise to red tape in business and contributed to bribery of clerks and clerks.

The role and size of the bureaucratic layer in management structures also steadily increased. If in 1640 there were 837 clerks, then by the end of the century there were almost 3 thousand people.

The local government system was changing. The role of elected (zemstvo) elders was increasingly narrowed, but the role of governors appointed by Moscow increased. The country was divided into counties, which in turn were divided into volosts and camps. At the head of each territorial unit there were governors who, being “on the sovereign’s salary,” collected taxes from the population, robbing them in the process.

“The time that immediately followed the Troubles,” writes historian S.G. Pushkarev, - demanded strong government power at the local level, and so, the “voivodes”, who had previously been mainly in the border regions “to guard” from enemies, in the 17th century. appear in all cities of the Moscow State, throughout its vast expanse, from Novgorod and Pskov to Yakutsk and Nerchinsk! Voivodes concentrate all military and civil power in their hands. Voivodes act according to the “mandates” (instructions) of Moscow orders, to which they obey. Only provincial institutions with provincial elders at their heads are preserved as a special, formally independent department. Zemstvo institutions in posads and volosts are also preserved, but during the 17th century they were They are increasingly losing their independence, increasingly turning into subordinate, auxiliary and executive bodies of the voivodeship administration. In the period from the 50s of the 16th century. until the 50s of the 17th century. The Moscow state can be called an autocratic zemstvo state. From the half of the 17th century. it becomes autocratic-bureaucratic. In the northern regions and in the 17th century. The peasant “world” is preserved - the volost assembly with its elected bodies, but the scope of their competence is increasingly narrowed. The volost court is subject to the supervision of the voivode and now decides only minor cases. The government begins to interfere in the economic life of peasants, limiting (or trying to limit) their right to freely dispose of land. The townspeople and peasant worlds bear collective responsibility for the proper collection of state taxes, and the main responsibility of the elected peasant authorities becomes the timely and “tax-free” collection of these taxes, and the main concern of the governors becomes coercion and punishment of those who, through their “oversight and negligence,” allow shortfalls and late payments."

Thus, the second half of the 17th century. is a time of decline of the zemstvo principle and growing bureaucratization in the central and local government of the Moscow state.

It was an objective process. It is due to a number of new phenomena. The feudal class consolidated. Gradually but steadily the differences between patrimonial and local forms of land ownership were erased. The boyars and nobility merged into a single class-estate, as evidenced by the Council Code of 1649, which allowed the exchange of an estate for a votchina, an estate for an estate. This meant that the estate ceased to be a personal and conditional possession and, like the estate, acquired hereditary status.

The legal immaturity of the classes, especially the tax people (the bulk of the population), characteristic of traditional society, contributed to the concentration of power and its self-organization. This process was also fueled by the fact that in the country, albeit slowly, more rational social relations were maturing, inevitable in the context of the growth of commodity-money exchange and the formation of new bourgeois relations in the depths of mature feudalism. It should be remembered that two more factors acted in favor of the self-organization of the authorities: the territorial vastness of the country and the constant tension on its borders, which forced the authorities not only to preserve the autocratic tradition, but to lead it to absolutization.

In the 17th century The principles of army organization, its personnel and functions changed. Its main responsibility was not only to protect the territory of the feudal state from external attack, but also to maintain internal order and obedience of the masses to the king. Although the combat effectiveness of the Streltsy army was relatively low, under Alexei Mikhailovich the number of Streltsy reached 40 thousand. But this force was not the main one. At the same time, another type of army is being created. Already under Mikhail Fedorovich, the first regiments of the new, or “foreign system” appeared - soldiers (infantry), reiters (cavalry) and dragoons (mixed formation). These regiments were staffed by the children of the boyars (reitars) and various kinds of free “willing” people (soldiers and dragoons). The training of new formations was carried out by hired foreign officers. The treasury provided these regiments with weapons, equipment and paid salaries. In the 17th century regiments of the new system were created temporarily, for the period of the war, and were disbanded at the end of hostilities. Only foreign mercenary officers remained in the service and pay of the Moscow government; they lived in the German settlement near Moscow. But by the end of the century, soldier regiments began to be staffed from among the “dating people”, i.e. peasants and townspeople. Every 20-25 households gave one man to serve as a soldier for life. This system formed the basis for the formation of the army under Peter I (recruitment).

By 1680, the Russian army had 41 regiments of soldiers (61,288 people) and 26 regiments and spear regiments (30,472 people). The number of boyar militia decreased to 27,927 people, about 20 thousand archers remained. Thus, the nascent regular army became increasingly important in maintaining and strengthening the autocratic-monarchical system in Russia.

The Code of 1649 is another evidence of the movement towards absolutism, the strengthening of central power, and the increasing role of the nobility. The Zemsky Sobor, which adopted new Russian legislation, is notable for the fact that it was assembled on the initiative of the zemshchina. Elected people at the Council itself took part in the drafting of all parts of the Code, even those that did not concern their own interests. This caused discontent among the Moscow boyar and administrative bureaucracy. Due to her governmental position, she could not accept such rules of interaction between government and society, much less allow them as a norm of social cooperation.

Historian S.F. Platonov comes to the following conclusion on this issue: “Serving in the 17th century. the political body of the middle classes of Moscow society, the Councils were at first in close unity with the monarch, who at the time of his election was himself the favorite leader of the same middle classes. The friendly co-government of two kindred political authorities, the tsar and the Council, lasted until the supreme power was emancipated from class influences and until a courtly aristocratic bureaucracy formed around it. At the first signs of discord between the zemstvo representation and “ strong people", between the lower and upper houses of the Zemsky Sobor in 1648, the government environment ceases to use the help of the Council... The Zemsky Sobor is no longer trusted because they associate its activities with that “great turmoil in the world” that shook the state in 1648-1650. The authorities are no longer looking for further support in the Councils, but in their own executive bodies: the bureaucratization of management begins, the “command” principle, to which Peter the Great gave full expression in his institutions, triumphs.”

By the first quarter of the 18th century. refers to the final approval and formalization of absolutism in Russia. It is associated with the radical transformations of the entire political system of the state undertaken by Peter I.

As a result of the public administration reform, a new vertical of central institutions emerged: the emperor - the Senate as an executive and administrative body - collegium as public and state bodies in charge of the most important areas of public administration. The activities of the Senate and collegiums were regulated by strict legal norms and job descriptions. In this vertical of power, the principle of subordination of lower bodies to higher ones was clearly implemented, and it was focused on the emperor.

Provincial reform of 1708-1710. changed the system of local government. Local self-government was liquidated, and at the head of all territorial-administrative units were placed persons who carried out state service and received salaries for it - governors, provincial commissioners, district and volost governors. The principle of interaction between these local authorities is the same - subordination from bottom to top.

Church reform turned the church organization into part of the state apparatus. The Synod, as the highest body of the church organization, was already perceived by Peter I's contemporaries as the 13th collegium.

Administrative transformations completed the formation of an absolute monarchy in the political system of Russia. Acceptance of the title by Peter I emperor was not only an external expression, but also evidence of absolutism established in Russia: “... His Majesty is an autocratic monarch, who should not give an answer to anyone from above about his affairs, but he also has his own power and authority to the state and lands, like a Christian sovereign , to rule according to your own will and good will,” read the 20th article of the Military Regulations.

- What reforms of the 50s of the 16th century. contributed to the strengthening of the Russian state and the formation of an estate-representative monarchy?

- Name the specific features of the Russian estate-representative monarchy of the 16th-17th centuries.

- What distinguished Zemsky Sobors in Russia from estate-representative institutions in Western Europe?

- How to explain that historical fact, that during the period of the oprichnina and in the subsequent years of his reign, Ivan IV did not eliminate the practice of convening Zemsky Sobors?

- What were the political possibilities of an estate-representative monarchy in the 16th-17th centuries?

- What stages in the development of the estate-representative monarchy in Russia can be identified? Determine the chronological framework of each of them and provide arguments for your gradation.

- What processes in the country's social life contributed to the transition from an estate-representative monarchy to absolutism? When did this process begin and what exactly was it accompanied by?

- As a result of what reforms of Peter I the zemstvo element in the management system was finally eliminated and the political institutions of an absolute monarchy were formed?

Apparently, the boyars themselves did not realize how radically they were breaking the old order, turning a historically customary relationship into a legally binding relationship. This is probably why the new thought was not a new beginning in the structure of the Moscow state. 49 Thus, the Boyar Duma, which throughout the turmoil tried to expand its competence, eventually ceded its powers to the Zemsky Sobor, which began to play a huge role in the beginning of Mikhail’s reign.

3. XVII century. The transition from estate-representative monarchy to absolutism.

In the 17th century With the establishment of a new dynasty in Russia, the estate-representative monarchy began to be restored. Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov ascended the throne very young, at 16 years old. He, of course, needed support. First he finds her in the person of his mother, Marfa, and his maternal relatives - the boyars Saltykovs. But in 1619, the tsar’s father, Filaret, returned from Polish captivity, proclaimed Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus', becoming Michael’s de facto co-ruler.

Under the new tsar, as in times of troubles, the boyars tried in every possible way to limit the sovereign's power. That's why Russian monarchy XVII century often called an autocracy with a Boyar Duma, which still remains the supreme body on matters of legislation, administration and justice. The king regularly consulted with her. But the composition of the Duma has changed significantly. In the 17th century the number of its members was constantly increasing. In 1613 it included 29 people, in 1675 – 66, in 1682 – 131. Among the members of the Duma were boyars, Duma nobles and Duma clerks. The main role belonged to the boyars. In fact, the boyars, having united in Moscow in the Boyar Duma, felt themselves to be the rulers of the Russian land. And all significant matters were decided “according to the boyar’s verdict and decree of the sovereign.” 50

At the same time, along with the “big” Boyar Duma, a small Duma appeared, “close”, “secret”, “room” - a group of the most proxies king Together with the Duma members, persons who were not members of the “big” Duma could participate in it; everything depended on the will of the sovereign. Gradually her role increased; The “big” Duma, on the contrary, was falling 51. This was largely due to its large composition. So, if earlier the Duma could meet every day and quite promptly, now it was difficult to do this. She began to gather only on solemn, ceremonial occasions. The actual functions of the Duma began to be carried out only by the “close” Duma, which, since the time of Alexei, became a permanent institution, consisting of a certain number of persons and acting on behalf of “all boyars.”

At the beginning of Mikhail's reign, Zemsky Sobors played a huge role, which were convened almost annually. At first they expressed the will of “the whole earth,” but later, when Mikhail’s father returned from Polish captivity, a permanent government was formed and the role of the council deputies was reduced to raising petitions before the supreme power 52 . From the second half of the 17th century. the convening of Zemsky Sobors ceases altogether. In 1651 and 1653 they convene for the last time in full. Then they turn into conferences of kings with representatives of classes on certain issues.

Thus, during the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich (1645-1676), a new trend in the development of the country’s political system was clearly identified - the transition from an estate representative monarchy to an absolute monarchy.

Absolutism is a form of feudal state in which the monarch has unlimited supreme power. With absolutism, the state achieves highest degree centralization. The absolute monarch rules, relying on the bureaucratic apparatus, a standing army and police, and the church is subordinate to him.

In January 1649, the Zemsky Sobor adopted the Council Code, which consisted of 25 chapters and 967 articles. Its main focus was on judicial proceedings and criminal law. In accordance with the second chapter of the Code “On State Honor and How to Protect Its State Health,” containing 22 articles, the death penalty was provided for even for criminal intent against the monarch 53 . The Code also recorded the position of various classes in the state, the procedure for military and public service, and issues of public administration in the center and locally. Thus, a serious step was taken in the direction of movement towards absolutism. After the adoption of the Code, legal acts appeared in the legislative practice of the Russian state, issued on behalf of the monarch, in which the Boyar Duma did not take part.

An important step in limiting the special position of the boyars was the act of abolishing localism in 1682. Thus, aristocratic origin loses importance when appointed to senior government positions. It is replaced by length of service, qualifications and personal devotion to the sovereign and the system. These principles would later be formalized in the Table of Ranks (1722). Klyuchevsky writes that “the abolition of localism in 1682 marked quite precisely the historical hour of its death as a government class” 54. Klyuchevsky also notes that in the 17th century. The boyars, who had already achieved significant success in their economic work after the shocks, disappeared as political power, lost in society with a new set of concepts and classes, dissolving into the serving noble masses.

The final formation of absolutism and its ideological justification dates back to the beginning of the 18th century, when Peter I, in his interpretation of Article 20 of the Military Regulations (1716), wrote that “...his Majesty is an autocratic Monarch who does not give an answer to anyone in the world about his affairs.” must; but the States and lands, like a Christian sovereign, have the power and authority to rule according to their own will and good will” 55 .

Already by early XVIII century, as new bodies of power and administration are formed in the Russian state, the Duma ceases to act as a body of representative power of the boyars. In 1699, under the Boyar Duma, the Near Office was established for financial control over the receipt and expenditure of funds from all orders. Soon her competence expanded. As a result, it becomes the meeting place of the increasingly shrinking Boyar Duma. In 1708, as a rule, 8 people participated in the meetings of the Duma, all of them administered various orders, and this meeting was called the Council of Ministers. At its meetings, various issues of government were discussed. The council of ministers, unlike the Boyar Duma, met without the tsar and was mainly occupied with carrying out his instructions. This was an administrative council answerable to the king.

N.M. Karamzin comments on the changes that were carried out during the reign of Peter: “For centuries, the people got into the habit of honoring the boyars as men marked by greatness - they worshiped them with true humiliation, when they, with their noble squads, with Asian pomp, to the sound of tambourines they appeared on the hundred, marching to the temple of God or to the council of the sovereign. Peter destroyed the dignity of the boyars: he needed ministers, chancellors, presidents! Instead of the ancient glorious Duma, the Senate appeared, instead of orders - collegiums, instead of clerks - secretaries, and so on. The same meaningless change for Russians in the military ranks: generals, captains, lieutenants expelled governors, centurions, Pentecostals, etc. from our army. Imitation has become the honor and dignity of Russians” 56.

Thus, by 1710, the Boyar Duma itself turned into a rather close council of ministers (the members of this close council are called ministers in Peter’s letters, in papers and acts of that time) 57 . But after the formation of the Senate, the Council of Ministers (1711) and the Near Chancellery (1719) ceased to exist. Thus, the centuries-old history of the existence of the Boyar Duma ended, and at the same time, the absolute power of the monarch was finally established in the country.

Conclusion.

The Boyar Duma has gone through a long, centuries-old history: from the Princely Duma of the times of Vladimir the Saint to the Council of Ministers during the reign of Peter I.

Century after century, the state apparatus, the volume of princely power, and the territory of the state changed. At the same time, the functions, composition and position of the Boyar Duma changed.

We find the first mentions of the Princely Duma, which was a permanent council under the prince, which included his closest associates, from the first pages of the Old Russian chronicle, continuing throughout the entire appanage period.

By the beginning of the 14th century. and especially from the end of the 15th century, the boyars can already be spoken of as the highest government officials. In the 16th century the word “boyar” transforms its meaning, and now it is, first of all, a member of the council under the Grand Duke, to whom the boyar rank was “confirmed” officially.

The special nature of the development of the political system of the Moscow state was predetermined by its “patrimonial” features. All power was concentrated in the hands of the autocratic monarch, who purposefully and steadily built it along a strict vertical line. The distribution of positions in government bodies was carried out on the basis of a unique system - “localism”.

At the same time, in the 16th century. as a single centralized state and, accordingly, state property takes shape, the political rights of the boyars are limited; Changes also occur in the social composition of the boyars. The grand ducal government, and subsequently the royal government, persistently suppressed the actions of those boyars who resisted its policy of centralization. In the era of Ivan the Terrible, the tsar, driven by the idea of strengthening central power, established oprichnina in Rus', which ultimately did not lead to the expected results. But nevertheless, this greatly weakened the boyars and their power.

IN early XVII c., during the Time of Troubles, the boyars were rehabilitated. They play a huge role in political life countries, it is their voice that becomes decisive in relation to all the most important issues. At the same time, the importance of the Zemsky Sobor is increasing, in whose activities the people see the source of justice and fairness. So, in January 1613, the Zemsky Sobor elected a new tsar - Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov. Under the new tsar, as in times of troubles, the boyars tried in every possible way to limit the sovereign's power. Therefore, the Russian monarchy of the 17th century. often called an autocracy with a Boyar Duma, which still remains the supreme body on matters of legislation, administration and justice.

Thus, in the XVI-XVII centuries. a sovereign without a Duma and a Duma without a sovereign, from the point of view of people of that time, were equally abnormal phenomena. The Code of 1649 recognizes boyar sentences as legislative sources on a par with state decrees. The inseparability of the tsar and the Duma was reflected in the general legislative formula “the tsar indicated and the boyars sentenced.” 58

But already from the second half of the 17th century. a new trend in the development of the country's political system is clearly indicated - the transition from an estate-based representative monarchy to an absolute monarchy. Thus, Zemsky Sobors, whose activity during Mikhail’s reign was almost continuous, ceased to be convened, and the Boyar Duma, expanding in its composition, received less and less opportunity to gather for meetings. As a result, the Middle Duma is formed, which since the time of Alexei has become a permanent institution, consisting of a certain number of persons and acting on behalf of “all boyars.”

With the adoption of the Council Code in 1649, a serious step was taken in the direction of movement towards absolutism. After the adoption of the Code, legal acts appeared in the legislative practice of the Russian state, issued on behalf of the monarch, in which the Boyar Duma did not take part.

An important step in limiting the special position of the boyars was the act of abolishing localism in 1682. Thus, aristocratic origin loses importance when appointed to senior government positions.

Already by the beginning of the 18th century, as new bodies of power and administration were formed in the Russian state, the Duma ceased to act as a body of representative power of the boyars. At the same time, absolutism is finally taking shape.

In 1699, the Near Chancellery was established under the Boyar Duma, which eventually became the seat of the increasingly shrinking Boyar Duma. Further, the activities of the Near Chancellery turn into permanent meetings of the Council of Ministers, consisting of 8 people. But after the formation of the Senate, the Council of Ministers (1711) and the Near Chancellery (1719) ceased to exist, along with the centuries-old history of the existence of the Boyar Duma.

According to a number of scientists, the Boyar Duma played such a significant role in government that the Russian statehood of the Moscow period can be called oligarchic. 59 However, the new era required radical changes. Thus, the early form of absolutism, which developed in the second half of the 17th century. with the Boyar Duma and the boyar aristocracy, turned out to be insufficiently adapted to solving the emerging domestic and especially foreign policy problems. But only noble empire, formed as a result of the reforms of Peter I, with its extreme authoritarianism, extreme centralization, powerful security forces, a powerful ideological system in the form of the Church, an effective system of control over the activities of the state apparatus, turned out to be able to successfully solve the problems facing the country.

1 24 – (on page 49) see Vladimirsky-Budanov M.F. Decree. op. – P. 44-51, Presnyakov A.E. Decree. op. – T. II. – P. 371-504.

2 Kolesnikov, V.N. People's government and parliament. – St. Petersburg: publishing house SZAGS, 2006. – P. 86

3 Ibid., p. 87

4 Vladimirsky-Budanov, M.F. Decree. op. pp. 177-180

5 Russian legislation of the X-XX centuries... T.2: Legislation of the period of formation and strengthening of the Russian centralized state. P.120

6 History of state and law of Russia. Course of lectures - Belkovets L.P., Belkovets V.V. http://vuzlib.net/beta3/html/ 1/11137/

7 Solovyov S. M. History of Russia since ancient times. Book III. 1463-1584 http://www.litru.ru/?book= 25441&description=1

8 Zagoskin N.P. History of law of the Moscow State. History of central administration in the Moscow state. According to the edition of 1879 (News and scientific notes of Kazan University) // Allpravo.Ru - 2004 http://www.allpravo.ru/ library/doc313p0/instrum2850/ print2851.html

9 Eremin p. 16

10 V.O.Klyuchevsky. Boyar Duma of Ancient Rus' http://www.sedmitza.ru/text/ 438814.html

11 Terminology of Russian history. Vasily Klyuchevsky http://vivatfomenko.narod.ru/ lib/terminologiya.html

12 In monuments of the 11th, 12th centuries. the components of the squad are designated by such terms as “boyars” and “grid”. The word “boyars” denoted the senior squad, therefore, the junior squad consisted of “gridi”, or the so-called “youths” and “children”. Thus, “grid” is the oldest term denoting a junior squad

13 Terminology of Russian history. Vasily Klyuchevsky http://vivatfomenko.narod.ru/ lib/terminologiya.html

14 http://www.sedmitza.ru/text/ 438817.html V.O. Klyuchevsky. Boyar Duma of Ancient Rus' (chapter 2)

15 Eremyan, p.16

16 Ibid., p. 17

17 Vernadsky G., p. 51

Article 18 THE FIGHT AGAINST JUDICIAL ARRICTRY OF OFFICIALS IN MOSCOW Rus' (XVI-XVII centuries)

Description

Objectives of this coursework:

1) consider the process of formation of the boyars as an estate, as well as the process of formation of the Boyar Duma.

2) analyze what the significance of the Boyar Duma was in the 15th-16th centuries.

3) consider the role of the boyars in political life during the Time of Troubles.

4) identify patterns of gradual weakening of the role of the Boyar Duma in the conditions of the emergence of absolutist tendencies.

Boyar Duma in the Time of Troubles.

The beginning of the Troubles. Her reasons. Change in the position of the boyars.

Boyars in the Time of Troubles.

Results of the Troubles.

17th century The transition from estate-representative monarchy to absolutism.

CONCLUSION

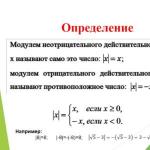

Practical lesson No. 4. terms: Estates-representative monarchy- a form of government that provides for the participation of class representatives in governing the state and drawing up laws. Absolute monarchy (from Latin absolutus - unconditional)- a type of monarchical form of government, in which the entirety of state (legislative, executive, judicial), and sometimes spiritual (religious) power is legally and actually in the hands of the monarch. Split

A church schism was originally considered to be any falling away from the Church of a group of believers. Schism of the Christian Church- the church schism of 1054, after which the Church was finally divided into Roman Catholic and Orthodox. Reiters(German Reiter - “horseman”, short for German Schwarze Reiter - “black horsemen”) - mercenary horse regiments in Europe and Russia in the 16th-17th centuries. The name "Black Riders" was originally used to refer to mounted mercenaries from southern Germany who appeared during the Schmalkaldic War between German Catholics and Protestants. Old Believers, Old Orthodoxy- a set of religious movements and organizations in line with the Russian Orthodox tradition, rejecting the church reform undertaken in the 1650s - 1660s by Patriarch Nikon and Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, the purpose of which was to unify the liturgical rite of the Russian Church with the Greek Church and, above all, with the Church of Constantinople.

Formation of an absolute monarchy in Russia in the 2nd half. XVII century

1. The transition from an estate-representative monarchy to an absolute one. Features of the formation of an absolute monarchy in Russia.

An estate-representative monarchy is a type of power where the monarch, in leading the country, relies primarily on estate-representative institutions. These representative institutions express the interests of all free classes of society. An estate-representative monarchy in Russia began to take shape already in the 15th century. during the period of completion of the political process of unification of Rus'. Then, under the sovereign of all Rus' Ivan III, the Boyar Duma acted as a permanent advisory body in the system of supreme power.

In its most complete form, the estate-representative monarchy took shape in Russia in the middle of the 16th century, when, along with the Boyar Duma, a new political structure began to operate in the system of public administration - Zemsky Councils, which became the dictate of the time along with the reforms of the mid-16th century.

A period of transformations began, called the “reforms of the 50s.” XVI century

Researchers highlight the following specific features Russian estate-representative monarchy of the 16th - 18th - 17th centuries:

1. Zemsky councils were convened at the will of the tsar, and therefore not periodically, but as needed;

2. They had no legal status and did not have the right of legislative initiative; their right is to discuss and make decisions on those issues that are put before the Council by the Tsar;

3. There was no elective election of deputies-representatives to the Councils. As representatives from the estates, mainly persons from local self-government were invited: heads and elected local noble and townspeople societies: zemstvo judges, provincial and townsman elders, favorite heads, kissers; from peasant communities - village elders.

From the second half of the 17th century. the transition to absolutism began. Absolutism is an unlimited monarchy in which all political power belongs to one person.

The establishment of absolutism was accompanied by the gradual withering away of medieval representative institutions, which during the period of the estate-representative monarchy acted along with royal power, as well as the weakening of the role of the church in government. Boyar Duma during the 17th century. turned from a legislative and advisory body into an advisory body under the king.

By the first quarter of the 18th century. refers to the final approval and formalization of absolutism in Russia. It is associated with the radical transformations of the entire political system of the state undertaken by Peter I.

Provincial reform of 1708-1710. changed the system of local government. Local self-government was abolished, and at the head of all administrative-territorial units were placed persons performing state service and receiving salaries for it - governors, provincial commissioners, district and volost governors.

Features of the formation of an absolute monarchy in Russia.

By the end of the 17th century. In Russia, an absolute monarchy begins to take shape, which did not arise immediately after the formation of a centralized state and the establishment of an autocratic system, because autocracy is not absolutism.

An absolute monarchy is characterized by the presence of a strong, extensive professional bureaucratic apparatus, a strong standing army, and the elimination of all class-representative bodies and institutions. These signs are also inherent in Russian absolutism. However, it also had its own significant features:

Absolute monarchy in Europe took shape under the conditions of the development of capitalist relations and the abolition of old feudal institutions (especially serfdom), and absolutism in Russia coincided with the development of serfdom;

The social basis of Western European absolutism was the alliance of the nobility with the cities (free, imperial), and Russian absolutism relied mainly on the serf-dominated nobility, the service class.

The establishment of an absolute monarchy in Russia was accompanied by widespread expansion of the state, its invasion into all spheres of public, corporate and private life. Expansionist aspirations were expressed primarily in the desire to expand their territory and access to the seas.

WITH 1708 Mr. Peter began to rebuild the old authorities and management and replace them with new ones. As a result, by the end of the first quarter of the 18th century. The following system of government and management bodies has emerged.

IN 1711 a new supreme body of executive and judicial power was created - the Senate, which also had significant legislative functions. It was fundamentally different from its predecessor, the Boyar Duma.

IN 1708 - 1709 gg. The restructuring of local authorities and administration began. The country was divided into 8 provinces, differing in territory and population.

Features of the absolute monarchy in Russia:

the establishment of serfdom, instead of the development of capitalism and the abolition of old feudal institutions (as was the case in Europe);

in Europe, the support of the monarch was the alliance of the nobility and the cities, in Russia - the feudal nobility and the service class.

From October 1721 Peter I is given the title of emperor for his victory in the Northern War and Russia becomes an empire.

The absolute monarchy was overthrown as a result of the February bourgeois-democratic revolution of 1917.

Ministry of Education Russian Federation

Moscow State University print

Part-time form of study

Department of History and Cultural Studies

Test

by discipline " National history»

Topic: “The evolution of Russian statehood:

from an estate-representative monarchy

to absolutism (XVI - early XVIII centuries) »

Moscow

1. Introduction – 3 pages.

2. Reforms of the 50s. XVI century and the establishment of an estate-representative monarchy in Russia – 4 pages.

3. Political features of Zemsky Councils of the 16th - 17th centuries – 19 pages.

4. Features of the establishment of absolutism in Russia – 21 pages.

5. Conclusion – 35 pages.

6. List of references used – 36.

EVOLUTION OF RUSSIAN STATEHOOD:

FROM THE REPRESENTATIVE MONARCHY

TO ABSOLUTISM ( XVI - START XVIII centuries)

1. Introduction

The development of Russia is inseparably linked with the growing power of Russian princes, tsars, and emperors. Basically, all reforms in Russia were aimed at maintaining and strengthening the vertical of central power. In the XVI - beginning. XVIII centuries The evolution of Russian statehood took place from an estate-representative monarchy to absolutism.

An estate-representative monarchy is a type of power where the monarch, in leading the country, relies primarily on estate-representative institutions that exist in the vertical of central power. These representative institutions express the interests of all free classes of society. An estate-representative monarchy in Russia began to take shape already in the 15th century. during the period of completion of the political process of unification of Russia. Then, under the sovereign of all Rus' Ivan III, the Boyar Duma acted as a permanent advisory body in the system of supreme power.

The Boyar Duma represented and expressed the interests of large landowners. The Boyar Duma under Ivan III and Vasily III performed two functions. Firstly, it provided support for the power of a single monarch-sovereign of all Russia. Secondly, it contributed to overcoming the elements and tendencies of feudal fragmentation and separatism.

In its most complete form, the estate-representative monarchy took shape in Russia in the middle of the 16th century, when, along with the Boyar Duma, a new political structure began to operate in the system of public administration - Zemsky Sobors or “councils of the whole earth,” as their contemporaries called them.

The appearance of Zemsky Sobors in the system of political power was not an accidental or temporary phenomenon. They became the dictates of the times, along with the reforms of the mid-16th century, which were energetically carried out by the Near Duma or the “Elected Rada” with the direct participation of Ivan IV.

The very name “Chosen Rada” belongs to Prince A. Kurbsky and was first used in his essay “The History of the Grand Duke of Moscow.” In fact, with this term he designated the circle of people close to the tsar who made up his Near Duma, with which he constantly consulted and whose participants were the government of Ivan IV. The Rada included A. Adashev and M. Vorotynsky, the Tsar’s confessor - the rector of the Annunciation Cathedral in the Kremlin, Archpriest Sylvester, and Prince A. Kurbsky.

Political development of Russia in the 16th century. it was going contradictory. The unification of Russian lands within a single state did not lead to the immediate disappearance of numerous remnants of feudal fragmentation. After the death of Vasily III (1505-1533), a fierce struggle between boyar groups for power began under the young heir. The political actions of the warring factions (the Shuiskys, Belskys, Glinskys, etc.) differed little from each other, but greatly weakened and disorganized the country's governance system, which was expressed in the growth of arbitrariness of the local rulers and the dissatisfaction of the tax and service population as a whole with the boyar rule.

2. Reforms of the 50s.

and the establishment of an estate-representative monarchy in Russia.

The beginning of the reign of young Ivan IV was already marked by a clear aggravation of social contradictions. The muted dissatisfaction of the masses with the endless princely-boyar intrigues and infighting, local lawlessness, bribery and other abuses of power resulted in a period of popular uprisings, the most significant of which was the Moscow uprising in the spring of 1547.

It should be borne in mind that during the unification of the country, the power of the Moscow sovereigns increased enormously, but did not become unlimited: the monarch shared power with the boyar aristocracy. Through the Boyar Duma, the nobility controlled the center, it commanded the troops, controlled all Local government (the boyars received the largest cities and counties of the country to “feed”).

Thus, in order to strengthen Russian statehood, it was necessary to speed up political centralization and rebuild the management system on a new basis with the inevitable strengthening of the power of the monarch. Many people in Rus' understood this. It is characteristic that among the members of the “Elected Rada” were Metropolitan Macarius, a native of the lower classes - a small Kostroma patrimonial landowner Alexei Adashev, a nobleman Ivan Peresvetov - people who were widely educated and passionate advocates of the ideology of autocracy. For the first time in the history of Russian social thought, I.S. Peresvetov formulated the idea of the impossibility of transforming the system of government and military service in Russia without limiting the political dominance of the nobility, without involving the nobility in state affairs. The 18-year-old tsar passionately supported these ideas and became the mouthpiece of the reformers when, speaking at the Council of the Hundred Heads (1551), he proposed an extensive program of reforms.