PART TWO

LECTURE XIV

The reign of Emperor Nicholas I. - The conditions under which he ascended the throne. - The question of succession to the throne. – Alexander’s unpublished manifesto on the abdication of Constantine. – Confusion and interregnum after the death of Alexander until December 14, 1825 . – Negotiations between Nicholas and Konstantin. - Accession to the throne of Nicholas. – Uprising of December 14, 1825 . -His suppression. – Personality of Emperor Nicholas. – Biographical information about him before his accession. – Investigation into secret societies. – The reprisal against the Decembrists and the results of Emperor Nicholas’ acquaintance with them. – Karamzin’s influence and the reign program inspired by him.

Circumstances of Nicholas I's accession to the throne

By the time Emperor Nicholas ascended the throne, many difficult, unfavorable circumstances had accumulated in the course of internal government and in general in the state of affairs within Russia, which in general created an extremely confusing and even quite formidable situation for the government.

Since the beginning of Alexander’s reign, as we have seen, many raised and unresolved questions have accumulated, the resolution of which was impatiently awaited by the advanced part of society, accustomed to an oppositional attitude towards the government since the time of the Tilsit Peace and the Continental System and managed, after close communication with Europe in 1813–1815 years, to develop certain political ideals. These ideals were completely contrary to the reactionary direction of the government, which was expressed towards the end of Alexander’s reign in the most obscurantist and absurd forms. All this, as we have seen, led little by little not only to acute discontent and unrest among the progressive intelligentsia, but to the formation among them of a direct conspiracy that set itself sharply revolutionary goals.

This revolutionary movement ended, due to random circumstances, with a premature and unprepared explosion on December 14, 1825 - an explosion that helped Nicholas's government quickly liquidate and suppress this movement with brutal repressive measures. As a result, the country lost the best and most living and independent representatives of an advanced thinking society, the rest of which was intimidated and terrorized by government measures, and the government turned out to be completely disunited in the difficult work ahead of it with the mental forces of the country for the entire duration of Nicholas's reign.

Meanwhile, even more important and difficult than the political and administrative tasks facing Nicholas were those socio-economic tasks that had matured by the time of his reign under the influence of the development of the general social process in Russia, the course of which, as we have seen, intensified and accelerated under influence of the Napoleonic wars. The development of this process continued to move and intensify throughout the reign of Nicholas and ultimately led to a crisis that occurred under the influence of a new external push - the unsuccessful Crimean campaign, which brought onto the historical stage with fatal necessity the period of great transformations of the 50s and 60s.

We now have to study the events and facts in which the course of this process was manifested.

The accession to the throne of Emperor Nicholas occurred in exceptional circumstances, due to the unexpected death of Emperor Alexander and his very strange orders on the issue of succession to the throne.

According to the law on succession to the throne on April 5, 1797, issued by Emperor Paul, if the reigning emperor does not have a son, he should be succeeded by the brother who follows him. Thus, since Alexander had no children at the time of his death, his next brother, Konstantin Pavlovich, should have succeeded him. But Konstantin Pavlovich, firstly, from a very early age had, as he stated more than once, the same aversion to kingship that Alexander himself initially expressed; on the other hand, circumstances occurred in his family life that formally made it difficult for him to ascend the throne: even at the beginning of Alexander’s reign, Constantine separated from his first wife, who left Russia in 1803. Then they lived apart for a long time, and Konstantin finally raised the issue of dissolving this marriage, achieved a divorce and married a second time to the Polish Countess Zhanneta Grudzinskaya, who received the title of Her Serene Highness Princess Łowicz. But this marriage was considered morganatic, and therefore not only their children were deprived of the right to the throne, but Konstantin Pavlovich himself, by entering into this marriage, seemed to be thereby renouncing the throne. All these circumstances raised the question of the transfer of the rights of succession to the throne to the brother next to Constantine during the reign of Alexander. Despite this, Konstantin Pavlovich, until Alexander’s death, continued to be considered the heir to the throne and bear the associated title of Tsarevich. The next brother after him was Nikolai. Although Nicholas later said more than once that he did not expect that he would have to reign, in essence, the fact that he was the natural successor to the throne after the removal of Constantine was obvious to all persons who knew the law of succession to the throne. Alexander himself made very clear hints to Nicholas back in 1812 that he would have to reign, and in 1819 he directly told him this, warning him about the possibility of his abdication in the near future.

In 1823, Alexander recognized the need to make a formal order in this regard - not so much in the event of his death, but in the event of his own abdication of the throne, which he was strongly thinking about at that time.

Having talked with Constantine back in 1822, Alexander then received from him a written abdication of the throne; then a manifesto was drawn up about this abdication, signed by Alexander, in which he recognized Constantine’s abdication as correct and “appointed” Nicholas as heir to the throne. This was also fully consistent with the fact that upon Alexander’s accession the oath was taken to him and the heir “who will be appointed.”

But this manifesto about the abdication of Constantine and the appointment of Nicholas as heir was surprisingly not published. Instead of publishing it, Alexander secretly ordered Prince A.P. Golitsyn to make three copies of it, then the original was transferred to Metropolitan Philaret for placement on the throne of the Assumption Cathedral in Moscow, where it was to be kept in deep secrecy, and copies were transferred to State Council, to the Senate and to the Synod for storage in sealed envelopes with the inscription on the envelope transferred to the State Council, by the hand of Alexander: “Keep in the State Council until my demand, and in the event of my death, disclose, before any other action, in an emergency meeting " There were similar inscriptions on the other two envelopes. All these copies were copied by the hand of Prince Golitsyn, and except for the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna and Konstantin, who, however, did not see the manifesto (but apparently knew about its existence), the manifesto itself was known only to Prince Golitsyn and Filaret. The only thing that can be thought of to explain this behavior of Alexander is that Alexander did all this mainly in case of his renunciation, and since renunciation could only be an arbitrary act, he thought, of course, that the whole matter remained in his hands. hands.

When the news of Alexander’s death arrived in St. Petersburg on November 27, 1825, Nicholas considered it impossible to take advantage of the unpublished manifesto and, knowing from Miloradovich that the guard troops in St. Petersburg were by no means disposed in his favor, he did not want to ascend the throne until he had obtained from Constantine formal and solemn abdication in his favor. Therefore, he began by swearing allegiance to Constantine as the legitimate emperor and, without listening to Golitsyn, who insisted on printing the package with the manifesto kept in the State Council, he ordered the troops of the St. Petersburg district to immediately swear the oath to Constantine; and then, reporting all this and expressing his loyal feelings, he sent a special envoy to Constantine in Warsaw.

Constantine replied through his brother Michael, who was then visiting Warsaw, that he had long ago abdicated the throne, but responded with a private letter, without again giving this act any official character. Nikolai believed that such a letter was not enough, especially since the St. Petersburg Governor-General Count Miloradovich advised him, in view of the guard’s dislike towards him, to act as carefully as possible.

To avoid misunderstandings, Nicholas sent a new envoy to Warsaw, asking Konstantin to come to St. Petersburg and personally confirm his abdication. But Konstantin only reaffirmed in a private letter that he had renounced during Alexander’s lifetime, but could not come in person, and that if they insisted on this, he would leave even further.

Then Nicholas decided that he had to stop these negotiations, which had lasted for two whole weeks, and announce his accession to the throne himself. Actually, a manifesto about this was written by him, with the help of Karamzin and Speransky, already on December 12, but it was published only on the 14th, and on this date a general oath was appointed in St. Petersburg to the new emperor.

Decembrist revolt (1825)

At the end of this unusual interregnum, alarming news about the mood of minds in St. Petersburg and in Russia in general began to reach Nicholas in various ways; but Miloradovich, although he advised to act cautiously, denied the possibility of serious indignation right up to December 14th.

Meanwhile, members of the secret society who were in St. Petersburg decided to take advantage of this unprecedented confusion in their views; it seemed to them that there could not be a more favorable opportunity to raise an uprising and demand a constitution.

On December 14, when a manifesto was issued that Konstantin had renounced and that he should swear allegiance to Nicholas, members of the Northern Society, mainly guards officers and sailors, who gathered daily at Ryleev's, made an attempt to convince the soldiers that Konstantin had not renounced at all, that Nicholas was acting illegally and that one should therefore stand firm in his first oath to Constantine, while demanding a constitution. The conspirators managed, however, to rebel entirely in only one Moscow guards regiment; his example was followed by several companies of the guards naval crew and individual officers and lower ranks of other units of the troops.

Gathering on Senate Square, the rebels declared that they considered Constantine the legitimate emperor, refused to swear allegiance to Nicholas and demanded a constitution.

When the news of this reached Nicholas, he considered the matter very serious, but still wanted to take measures first to end it, if possible, without shedding blood. To this end, he first sent Miloradovich, who, as a famous military general, enjoyed significant prestige among the troops and was especially loved by the soldiers, to admonish the rebels. But when Miloradovich approached the mutinous units of the troops and spoke to them, he was immediately shot by one of the conspirators, Kakhovsky, and Miloradovich fell from his horse, mortally wounded. Since several batteries of artillery joined the rebels at that time, Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich volunteered to admonish them as the chief of all artillery, but he was also shot by Wilhelm Kuchelbecker, and Mikhail Pavlovich, although not wounded, had to, however Well, drive off. Then Metropolitan Seraphim was sent to admonish the soldiers, but they did not listen to him either and shouted to him to leave. Then Nicholas ordered, on the advice of the generals around him, to attack the rebel troops with the help of the horse guard, commanded by Alexey Fedorovich Orlov, the brother of the former member of the Union of Welfare, Mikhail Orlov. Orlov moved to attack, but his horses were not properly shod, meanwhile there was black ice, and they could not walk at a fast pace, since their legs were moving apart. Then the generals surrounding Nicholas began to say that it was necessary to put an end to this, because the population was little by little joining the rebels; Indeed, crowds of people and civilians appeared in the square. Then Nikolai ordered to shoot, after several shots of grapeshot at close range, the entire crowd rushed to run, leaving many dead and wounded. Not limited to this, out of inertia they also fired after the crowd when it rushed to run across the St. Isaac's Bridge (it was a bridge directly from Senate Square to Vasilievsky Island), and quite a lot of people were killed and wounded here.

This, essentially speaking, was the end of the entire uprising in St. Petersburg. All other troops swore allegiance without complaint, and the incident was over. Nikolai ordered that the next day no corpses or traces of what had happened would remain, and the obliging but unreasonable Chief of Police Shulgin ordered that the corpses be thrown directly into the ice hole, which is why rumors circulated for a long time that in the haste of this cleanup, the seriously wounded were also thrown into the ice hole along with the corpses . Subsequently, it was discovered that on the side of Vasilyevsky Island a whole row of corpses were frozen to the ice; Even an order was made not to take water here that winter and not to chop ice, because parts of the human body were found in the ice. Such a gloomy event marked the beginning of a new reign.

This was followed by searches and arrests throughout St. Petersburg. Several hundred people were arrested - many of them not involved in the case, but at the same time all the main leaders were arrested.

On December 10, Nikolai Pavlovich received the first warning from the young lieutenant Rostovtsev about the unrest being prepared in the guard, and at the same time, almost at the same time, he received from Dibich (chief of the main headquarters of His Majesty, who was under Alexander in Taganrog) copies of denunciations about a conspiracy in the Southern Society, where in January 1826, Sergei Muravyov also attempted an armed uprising at Belaya Tserkov. Therefore, the investigation began immediately about all the secret societies that existed in Russia at that time. This consequence filled the first months of Nicholas's reign.

Personality of Nicholas I

But before we begin to describe the first steps of the reign of Emperor Nicholas, it is necessary to give some information about his personality. Nicholas was the third son of Emperor Paul and after the death of his father he remained a five-year-old child. His upbringing was taken entirely upon himself by his mother, Maria Feodorovna, while Alexander, out of false delicacy, did not consider himself to have the right to interfere in this matter, although, it would seem, the upbringing of a possible heir to the throne is a public matter, not a private one. Subsequently, however, there were isolated cases of Alexander’s intervention in this matter, but they were rather to the disadvantage. Historians of the reign of Nicholas, or rather, his biographers - because the history of this reign does not yet exist - for the most part adhere to the view, very widespread among contemporaries of that era, that Nicholas was raised not as a future emperor, but as a simple grand duke, destined to military service, and this explains the shortcomings in his education, which were subsequently felt quite strongly. This view is completely incorrect, since for the members of the royal family it should have seemed quite probable from the very beginning that Nicholas would have to reign. Empress Maria Feodorovna, who knew that Constantine did not want to reign and that both Alexander and Constantine had no children, could not doubt this. Therefore, there is no doubt that Nicholas was brought up precisely as the heir to the throne, but his upbringing from the upbringing of Alexander nevertheless differed extremely greatly.

Maria Feodorovna, apparently, not only did not want to make him into a military man, but from childhood she tried to protect him from becoming interested in the military. This, however, did not prevent Nicholas from acquiring very early a taste for the military. This is explained by the fact that the very approach to education was unsuccessful, since neither the situation at court nor the pedagogical views of the empress were favorable to it. At the head of Nikolai’s educators, instead of Laharpe, who was under Alexander, an old German routiner, General Lamsdorf, was put in charge, whom Maria Feodorovna simply called “papa Lamsdorf” in intimate conversations and letters and who, in the old fashioned way, organized Nikolai’s education.

Nikolai was a rude, obstinate, power-hungry boy; Lamsdorff considered it necessary to eradicate these shortcomings with corporal punishment, which he used in significant doses. The fun and games of Nikolai and his younger brother always took on a military character; moreover, every game threatened to end in a fight thanks to Nikolai’s wayward and pretentious character. At the same time, the atmosphere in which he grew up was a court atmosphere, and his mother herself, Maria Fedorovna, considered it important to observe court etiquette, and this deprived the education of a family character. There is evidence that at an early age Nikolai showed traits of childish cowardice, and Schilder gives a story about how Nikolai, at the age of five, was frightened by cannon fire and hid somewhere; but it is hardly possible to attach special significance to this fact, if it occurred, since there is nothing special about the fact that a five-year-old boy was afraid of cannon fire. Nikolai was not a coward, and he subsequently showed personal courage both on December 14 and on other occasions. But his character from childhood was not pleasant.

As for the teachers who were assigned to him, what is striking is their extremely random and meager choice. For example, his tutor, the French emigrant du Puget, taught him both the French language and history, without being sufficiently prepared for this. All this teaching boiled down to instilling in Nikolai hatred of all revolutionary and simply liberal views. Nikolai studied extremely poorly; all the teachers complained that he was making no progress, with the only exception being drawing. Later, however, he showed great success in the art of military construction and showed a penchant for military sciences in general.

When he came out of childhood, very respectable and knowledgeable teachers were invited to him, precisely as the future heir to the throne: a rather respectable scientist, Academician Storch, was invited, who taught him political economy and statistics; Professor Balugiansky - the same one who was Speransky’s teacher in financial science in 1809 - taught Nikolai the history and theory of finance.

But Nikolai Pavlovich himself later recalled that he yawned during these lectures and that nothing remained in his head from them. Military science was read to him by the engineer General Opperman and various officers invited on Opperman’s recommendation.

Maria Fedorovna was thinking of sending both of her younger sons, Nikolai and Mikhail, to the University of Leipzig to complete their education, but then Emperor Alexander unexpectedly declared his veto and suggested instead sending the brothers to the then designed Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum, but when this lyceum was opened in 1811 ., then the entry of the great princes there also did not take place, and all their education was limited to homework.

In 1812, Nikolai Pavlovich, who was 16 years old at that time, very much asked to be allowed to participate in the active army, but Emperor Alexander refused him this and then for the first time hinted to him that he would have more to do in the future. important role, which does not give him the right to expose his forehead to the enemy’s bullets, but obliges him to make more efforts to prepare himself for his high and difficult mission.

Alexander allowed his brothers to join the active army only in 1814, but they were then late for military action and arrived when the 1814 campaign had already ended and the troops were in Paris. In the same way, Nikolai Pavlovich was late for the war of 1815, when Napoleon fled from the island of Elba and when Emperor Alexander again allowed his brother to join the troops. Thus, in fact, in the days of his youth, during the Napoleonic Wars, Nicholas was not able to even see the real battle from afar, but was only able to attend the magnificent reviews and maneuvers that followed at the end of the campaigns of 1814 and 1815.

To finish with the characterization of the upbringing of Emperor Nicholas, it must also be mentioned that in 1816 he traveled around Russia to familiarize him with the country, and then he was given the opportunity to travel around European courts and capitals. But these journeys were made, so to speak, by courier with dizzying speed, and the young Grand Duke could see Russia only superficially, only from its outer side, and then mostly for show. He also traveled around Europe in the same way. Only in England did he stay a little longer and saw parliament, clubs and rallies - which, however, made a repulsive impression on him - and even visited Owen in New Park and looked at his famous institutions, and Owen himself and his attempts to improve the fate of the workers then made a favorable impression on Nikolai Pavlovich.

It is remarkable that Maria Feodorovna feared that the young Grand Duke would not acquire a taste for English constitutional institutions, and therefore a detailed note was written for him by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Count Neselrode, with the goal of protecting him from possible hobbies in this regard. But the impressions that Nikolai Pavlovich gained from his trip to England showed that this note was completely unnecessary: obviously, by all his previous upbringing he had been insured against any passion for so-called liberalism.

This trip to Europe ended with Nicholas's matchmaking with the daughter of the Prussian king Frederick William, Princess Charlotte, with whom he married in 1817, and along with the Orthodox faith, his wife accepted the name of Grand Duchess Alexandra Feodorovna. In 1818, when Nikolai Pavlovich was only 21 years old, he had already become the father of the family: the young couple gave birth to the future Emperor Alexander Nikolaevich. The entire end of the reign of Alexander I passed for Nicholas partly in the joys of family life, partly in front-line service. Eyewitnesses testify that Nikolai was a good family man during these years and felt good in his family. His social activities during these years consisted exclusively of military service. True, Alexander, even at this time, repeatedly gave him hints about what awaited him ahead. So, in 1819, he had a very serious conversation with Nicholas, as I already mentioned, and Alexander definitely warned his younger brother and his wife that he was feeling tired and was thinking of abdicating the throne, that Constantine had already abdicated and that he would reign to Nikolai. Then, in 1820, Alexander summoned Nicholas to a congress in Laibach, saying that Nicholas should familiarize himself with the course of foreign affairs and that representatives of foreign powers should get used to seeing him as Alexander’s successor and continuator of his policies.

Grand Duke Nikolai Pavlovich, future Emperor Nicholas I

Despite, however, all these conversations, which always took place face to face, no significant changes followed in Nikolai’s external life. He was promoted to general back in 1817 and then almost until the end of his reign he was commander of the guards brigade; True, he had the honorary leadership of the military engineering department, but most of his time was spent commanding the brigade. This matter was boring and of little (instructive) for the future ruler of a great country. At the same time, it was also associated with troubles, since the main task of the Grand Duke was the restoration of external discipline in the troops, which had greatly wavered in them during foreign campaigns, in which officers got used to following the rules of military discipline only at the front, and outside it they considered themselves free citizens and even wore civilian dress. With these habits they returned to Russia, and Alexander, who was especially concerned about preserving the military spirit in the army and considered external discipline a very important matter , recognized the need to greatly tighten up especially the officers of the guard. In this matter of “pulling up” the guard, Nikolai Pavlovich appeared as one of the most devoted missionaries, who pulled up his brigade not out of fear, but out of conscience. He himself complained in his notes that it was necessary to do this It was quite difficult for him, since everywhere he encountered mute discontent and even protest, for the officers of his brigade belonged to the highest circles of society and were “infected” with freedom-loving ideas. In his activities, Nikolai often did not meet with approval from his highest authorities, and since he pedantically insisted on his own, his severity soon aroused almost universal hatred against himself in the guard, reaching such an extent that at the time of the interregnum of 1825, Miloradovich considered I am obliged, as I have already mentioned, to warn him about this and advise him to behave as carefully as possible, without counting on public sympathy for himself.

Alexander, despite the fact that for him it was apparently a foregone conclusion that Nicholas would reign after him, behaved very strangely towards him: he not only did not prepare him for the affairs of government, but did not even include him in the State council and other higher state institutions, so that the entire course of state affairs went past Nicholas. And although there is information that after Alexander’s decisive warnings, Nikolai Pavlovich himself changed his previous attitude towards the sciences and gradually began to prepare for the management of state affairs, trying to get to know them theoretically, but there is no doubt that he had little success in this, and he ascended the throne in the end ultimately unprepared – neither theoretically nor practically.

Those persons who stood close to him, such as V. A. Zhukovsky, who was first invited as a teacher of the Russian language to Grand Duchess Alexandra Feodorovna, and then became the teacher of her eldest son and entered quite deeply into their family life, testify to that Nikolai at home during this period was not at all the stern and unpleasant pedant that he was in his brigade. And indeed, his home environment was completely different from his military environment. His main friend in the service was General Paskevich, who was a strict, vain and soulless front-line soldier, who later played big role in organizing the Russian army in this particular direction. As for Nikolai’s family circle, he was surrounded by people such as V. A. Zhukovsky, V. A. Perovsky and other simple, intelligent and nice people who are rarely encountered in the court atmosphere.

Trial of the Decembrists

Having ascended the throne under the circumstances that I have already described, Nikolai Pavlovich considered his first task to be to investigate to the most hidden depths all the causes and threads of the “sedition”, which, in his opinion, almost destroyed the state on December 14, 1825. He, undoubtedly, exaggerated, especially at first, the importance and number of secret revolutionary societies, loved to express himself in exalted language regarding these events and his own role in them, presenting everything in a heroic form, although the riot that took place in St. Petersburg was actually due to material forces, which the conspirators had at their disposal on December 14, was, in essence, quite powerless and if they could have any success, it would be thanks to the phenomenal disorder that reigned in the palace at that time. The arrests and searches, which were carried out with a broad hand, covered barely a few hundred people in all of Russia, and of the five hundred people who were captured, most were subsequently released and freed from persecution. Thus, with all the rigor of the investigation and with the remarkable frankness of the majority of the accused in their testimony, in the end only 120 people were brought to trial.

But even after the end of the case, this conspiracy seemed monstrous and enormous to Nicholas, and he was firmly convinced that on December 14 he saved Russia from imminent death. Many close associates viewed the matter in the same way. It is very difficult to separate the assent and flattery here from a sincere representation of these events. At the coronation itself, when Nicholas entered the Assumption Cathedral, Moscow Metropolitan Philaret, who then had a reputation as a free-thinking bishop, said among other things in his speech: “The impatience of loyal desires would dare to ask: why did You delay? If we did not know that both Your present solemn coming was a joy to us, and Your previous delay was a blessing to us. You were in no hurry to show us Your glory, because You were in a hurry to establish our safety. You are coming, finally, as the king of not only Your inherited, but also Your preserved kingdom...”

There were quite a few people who imagined things exactly this way. And so Nicholas for the first six months of his reign, leaving aside all state affairs and even military affairs, directed all his forces to find the roots of the conspiracy and to establish his personal and state security. He himself appeared, if not directly as an investigator, then as a zealous supreme leader of the entire investigation that was carried out on the Decembrists. As an investigator, he was often biased and unbalanced: he showed great temper and a very uneven attitude towards persons under investigation. This was also reflected in the memoirs of the Decembrists. Some of them - who had to experience the comparatively humane attitude of the supreme investigator - praise him, others say that he attacked them with extraordinary irritation and lack of restraint.

Attitudes varied depending on preconceived views of some defendants, from different attitude to different persons and simply from Nikolai’s personal mood. He himself, in one of his letters to Konstantin, wrote with great naivety that by establishing the Supreme Criminal Court over the Decembrists, he set almost an example of a constitutional institution; from the point of view of modern justice, these words can only seem like ridicule. The whole matter came down to an inquisitorial investigation, extremely deep and detailed, by a special commission of inquiry led by Nikolai himself, which predetermined the entire end of the case. The Supreme Court was a simple solemn comedy. It consisted of several dozen people: it included senators, members of the State Council, three members of the Synod, then 13 people were appointed to this Supreme Sanhedrin by order of Emperor Nicholas - but no court, in the sense in which we are accustomed to understanding it there was, in fact, no word: no judicial investigation, no debate between the parties, there was only a solemn meeting of such a court, before which each defendant was brought separately; he was interrogated extremely briefly, and some were even only read a maxim, so that many of the defendants were sure that they had not been tried, that they had only been read the verdict of some mysterious inquisitorial institution. This is how the criminal side of this case was framed. Nikolai eventually showed great cruelty and mercilessness towards the defendants, but he himself believed, and, apparently, sincerely, that he was only showing complete justice and civil courage. And, it must be said that no matter how biased he was during the investigation, in the end he punished everyone equally mercilessly - both Pestel, whom he considered a fiend of hell and a highly evil person, and Ryleev, whom he himself recognized as extremely pure and whose exalted personality and family provided significant material support. According to the verdict of the Supreme Criminal Court, five people were sentenced to execution by quartering - Emperor Nicholas replaced the quartering with hanging; 31 people were sentenced to ordinary execution - by firing squad; Nikolai replaced it with hard labor - indefinite and sometimes for 15-20 years. Accordingly, he reduced the punishment for others; but most were still sent to Siberia (some after many years of imprisonment in fortresses), and only a few were sent to be soldiers without length of service.

For the subsequent course of government, the other side of this exceptional process was also important. Nikolai, trying to discover all the roots of sedition, to find out all its causes and springs, deepened the investigation to the extreme. He wanted to find out all the reasons for discontent, to find out the hidden springs, and thanks to this, little by little, a picture of those disorders in Russian social and state life of that time unfolded before him, the extent and significance of which he had not suspected before. In the end, Nicholas realized that these disorders were significant and that the discontent of many was justified, and already in the first months of his reign he declared to many people - including representatives of foreign courts - that he was aware of the need for serious changes in Russia. “I have distinguished and will always distinguish,” he told the French envoy Comte de Saint Prix, “those who want just reforms and want them to come from legitimate authority, from those who themselves would like to undertake them and God knows by what means.” .

By order of Nikolai, one of the clerks investigative commission(Borovkov) even drew up a special note, which included information about plans, projects and instructions received from the Decembrists during interrogation or reported in notes compiled by some of them on their own initiative, others at the request of Nicholas.

Thus, Nicholas quite consciously considered it useful and even necessary to borrow from the Decembrists, as very smart people who had thought through their plans well, everything that could be useful to him as material for state activities.

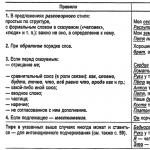

The mentioned note, compiled by Borovkov, in its conclusion outlined certain conclusions, of which, of course, only some were inspired by the testimony of the Decembrists, while others flowed from the general impression of the internal state of the state that became clear to Emperor Nicholas. Borovkov summarizes these conclusions about the urgent needs of public administration as follows: “It is necessary to grant clear, positive laws; to deliver justice through the establishment of the shortest legal procedure; to enhance the moral education of the clergy; to reinforce the nobility, fallen and completely ruined by loans from credit institutions; to revive commerce and industry by immutable statutes; to direct the education of youth in accordance with each condition; improve the situation of farmers; destroy the humiliating sale of people; resurrect the fleet; to encourage private people to sail, in a word, to correct innumerable disorders and abuses.” In essence, one could extract a whole state program, but Nikolai took into account from it only those facts and conclusions that most struck him.

In any case, among the Decembrists he saw for the most part not inexperienced young men who were guided by youthful ardor alone, but a whole series of people who had previously been involved in the affairs of the higher and local administration. Such was N.I. Turgenev - Secretary of State of the State Council and director of one of the departments of the Ministry of Finance, such was Krasnokutsky - Chief Prosecutor of the Senate, Batenkov - one of Speransky’s close employees, and at one time Arakcheev, Baron Steingeil - ruler of the Moscow Chancellery Governor General. Nikolai could not help but see the intelligence of such representatives of the Decembrists as Pestel and Nikita Muravyov, but even minor members secret societies, such as Batenkov or Steingeil, he could draw a lot of useful instructions.

When the Decembrist trial was over, in June 1826, and when five people considered the main conspirators were executed, the manifesto issued on the occasion of the coronation on July 13, 1826, highlighted Nicholas’s attitude towards secret societies and at the same time threw a look at his own future activities. “Not from daring dreams, which are always destructive,” it was said, by the way, in this manifesto, “but from above, domestic institutions are gradually improved, shortcomings are supplemented, abuses are corrected. In this order of gradual improvement, every modest desire for the better, every thought to strengthen the power of laws, to expand true enlightenment and industry, reaching us through a legal path, open to everyone, will always be accepted by us with favor: for we do not have, cannot have other desire than to see our Fatherland at its most high degree happiness and glory, predestined for him by providence.”

Thus, the manifesto, which appeared immediately after the massacre of the Decembrists, promised a series of transformations, and one can hardly doubt that Nicholas’s first intentions at the beginning of his reign were transformative intentions. The direction and content of these transformations should have depended on the general views and views of the young autocrat on the essence and tasks of state power in Russia.

Karamzin and the views of Nicholas I on domestic politics

Nikolai Pavlovich managed to understand and formulate for himself these general political views and views upon his very accession to the throne - mainly thanks to N.M. Karamzin, who undoubtedly appeared at this difficult moment as a mentor and intimate adviser to the new young and inexperienced ruler of Russia. If from the Decembrists Nikolai Pavlovich had to receive the first information that amazed him about the unrest and abuses in government affairs, then Karamzin had even earlier given him, one might say, a general program for the reign, which pleased Nikolai to such an extent that he was ready to make rich this irreplaceable person in his life. in the eyes of the adviser, who at that time already had one foot in the coffin.

Karamzin, as you know, never held any government post under Alexander, but this did not prevent him from sometimes acting as a strong and harsh critic of government measures - both at the time of the greatest flowering of liberal assumptions, in the era of Speransky, and at the end of the reign, when Karamzin sharply condemned Alexander's policy on the Polish issue and did not hide his negative views and on military settlements, and on the obscurantist activities of various Magnitskys and Runichs in the field of public education and censorship.

Upon the accession of Nicholas to the throne, Karamzin’s days were already numbered: on the very day of December 14, he caught a cold on Palace Square and although he then suffered for two months, he finally fell ill and died six months later, without using the frigate equipped by the highest order to transport sick historiographer to Italy. From the first days of the interregnum, which began on November 27, 1825, Karamzin, of his own volition, came to the palace every day and there he specially preached to Nicholas, trying to convey to him his views on the role of the autocratic monarch in Russia and on state tasks at this moment. Karamzin's speeches made a huge impression on Nikolai Pavlovich. Karamzin, skillfully able to maintain complete respect, even reverence for the personality of the just deceased sovereign, at the same time mercilessly criticized his government system - so mercilessly that Empress Maria Feodorovna, who was constantly present at these conversations and, perhaps, even contributed to their emergence , exclaimed one day when Karamzin was too harshly attacking some of the measures of the past reign: “Have mercy, have mercy on your mother’s heart, Nikolai Mikhailovich!” - to which Karamzin responded without embarrassment: “I’m saying not only to the mother of the sovereign who died, but also to the mother a sovereign who is preparing to reign."

What were Karamzin’s views on the role of autocracy in Russia, you already know from the contents of his note “On Ancient and new Russia", presented by him to Emperor Alexander in 1811. Nikolai Pavlovich could not have known this note then, because the only copy of it was given by Emperor Alexander Arakcheev and only in 1836 - after Arakcheev's death - was found in his papers. But Karamzin developed the same views later (in 1815) in the introduction to his “History of the Russian State,” and this introduction was, of course, known to Nikolai. In Karamzin’s mind, the thoughts expressed in the notes he submitted to Alexander (“On Ancient and New Russia” - in 1811 and “Opinion of a Russian Citizen” - in 1819) undoubtedly remained unchanged until the end of his life. Karamzin, faithful in this case to the view he borrowed from Catherine II, believed that autocracy was necessary for Russia, that without it Russia would perish, and he supported this idea with examples of moments of turmoil in the history of Russia, when autocratic power wavered.

At the same time, he looked at the role of an autocratic monarch as a kind of sacred mission, as a constant service to Russia, by no means releasing the monarch from his duties and strictly condemning such actions of sovereigns that, not corresponding to the benefits and interests of Russia, were based on personal arbitrariness , whim or even ideological dreams (like Alexander). The role of a subject in an autocratic state was depicted by Karamzin not in the form of wordless slavery, but as the role of a courageous citizen obliged to unconditional obedience to the monarch, but at the same time obliged to freely and sincerely express to him his opinions and views regarding state affairs. Karamzin's political views were, with all their conservatism, undoubtedly a utopia, but a utopia not devoid of a certain enthusiasm and sincere, noble feeling. They sought to give political absolutism a certain ideology and beauty and made it possible for autocracy, to which Nicholas was inclined by nature, to rely on a sublime ideology. They summed up the principle under Nicholas’s immediate and semi-conscious personal aspirations and gave the young autocrat a ready-made system that fully corresponded to his tastes and inclinations. At the same time, the practical conclusions that Karamzin made from his general views were so elementary and simple that they could not help but please Nikolai Pavlovich, who had become accustomed to the ideas of military front-line service from a young age. They seemed to him to be built on a wise and majestic foundation and at the same time were quite within his reach.

The views inspired by Karamzin did not exclude at the same time the possibility and even the need to begin to correct those abuses and disorders of Russian life that became clear to Nicholas during his relations with the Decembrists. Karamzin, for all the conservatism of his views, was neither a reactionary nor an obscurantist. He strongly condemned the obscurantist measures of the Ministry of Spiritual Affairs and Public Education and the fanatical exploits of Magnitsky and Runich, had a negative attitude towards the activities of Arakcheev and military settlements, and strictly condemned the abuses of financial management under Guryev. After December 14, 1825, he told one of the people close to him (Serbinovich) that he was “an enemy of the revolution,” but recognized the necessary peaceful evolutions, which, in his opinion, “are most convenient under monarchical rule.”

Nikolai Pavlovich’s confidence in Karamzin’s statesmanship was so strong that he was apparently going to give him a permanent government post; but the dying historiographer could not accept any appointment and instead of himself recommended to Nikolai his younger like-minded people from among the members of the former literary society "Arzamas": Bludov and Dashkov, who were soon joined by another prominent "Arzamas resident" - Uvarov, who later gave the final the formulation of that system of official nationality, the father of which was Karamzin.

For the most detailed description of the end of the day on December 14, 1825, see Art. M. M. Popova(famous teacher Belinsky, who later served in the III department), in Art. collection. "About the past." St. Petersburg, 1909, pp. 110;–121.

Shortly before Karamzin’s death, he was assigned a pension of 50 thousand rubles. per year with the fact that after death this pension was transferred to his family (cf. Pogodin."N. M. Karamzin", vol. II, p. 495, where the decree about this to the Minister of Finance dated May 13, 1826 is given).

Compare “Opinion of gr. Bludova about two notes by Karamzin", published in the book Eg. P. Kovalevsky“Gr. Bludov and his time". St. Petersburg, 1875, p. 245.

From among the former “Arzamas residents”, Pushkin was also allowed from the village to the capital, who brought complete repentance in 1826. He was summoned from the village to Moscow during the coronation, and it was ordered to send him from the Pskov province, although with a courier, but in his own crew - not as a prisoner. Emperor Nicholas received him personally, and Pushkin made a good impression on him with his frank and direct conversation. There is no doubt that in Pushkin, Emperor Nicholas, first of all, saw great mental strength and wanted to “attach this strength to business” and utilize it in the service of the state. Therefore, the first proposal he made to Pushkin was a business proposal - to draw up a note on measures to raise public education. Pushkin set to work very reluctantly, only after repeating this order through Benckendorff. This was unusual for the poet; however, he wrote a note and in it he conveyed the idea that enlightenment is very useful even for establishing a reliable direction of minds, but that it can only develop with some freedom. Apparently, Emperor Nicholas did not really like this, as can be seen from the following note reported to Pushkin by Benckendorff: “Morality, diligent service, diligence - should be preferred to inexperienced, immoral and useless enlightenment. Well-directed education should be based on these principles...” Compare. Schilder“Imper. Nicholas the First, his life and reign,” vol. II, p. 14 et seq.

Nicholas I Romanov

Years of life: 1796–1855

Russian Emperor (1825–1855). Tsar of Poland and Grand Duke of Finland.

From the Romanov dynasty.

In 1816 he made a three-month journey across European  Russia, and from October 1816. until May 1817 he traveled and lived in England.

Russia, and from October 1816. until May 1817 he traveled and lived in England.

In 1817 Nikolai Pavlovich Romanov married the eldest daughter of the Prussian King Frederick William II, Princess Charlotte Frederica-Louise, who took the name Alexandra Feodorovna in Orthodoxy.

In 1819, his brother Emperor Alexander I announced that the heir to the throne, the Grand Duke, wanted to renounce his right of succession to the throne, so Nicholas would become the heir as the next senior brother. Formally, Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich renounced his rights to the throne in 1823, since he had no children in a legal marriage and was married in a morganatic marriage to the Polish Countess Grudzinskaya.

On August 16, 1823, Alexander I signed a manifesto appointing his brother Nikolai Pavlovich as heir to the throne.

However, he refused to proclaim himself emperor until the final expression of the will of his elder brother. Refused to recognize Alexander's will, and on November 27 the entire population was sworn in to Constantine, and Nikolai Pavlovich himself swore allegiance to Constantine I as emperor. But Konstantin Pavlovich did not accept the throne, and at the same time did not want to formally renounce it as emperor, to whom the oath had already been taken. An ambiguous and very tense interregnum was created, which lasted twenty-five days, until December 14.

Emperor Nicholas I

After the death of Emperor Alexander I and the abdication of the throne by Grand Duke Constantine, Nicholas was nevertheless proclaimed emperor on December 2 (14), 1825.

By this day, the conspiratorial officers, who later began to be called “Decembrists,” ordered a mutiny with the aim of seizing power, allegedly protecting the interests of Konstantin Pavlovich. They decided that the troops would block the Senate, in which the senators were preparing to take the oath, and a revolutionary delegation consisting of Pushchin and Ryleev would burst into the Senate premises with a demand not to take the oath and to declare the tsarist government overthrown and to issue a revolutionary manifesto to the Russian people.

The Decembrist uprising greatly amazed the emperor and instilled in him fear of any manifestations of free-thinking. The uprising was brutally suppressed, and 5 of its leaders were hanged (1826).

After suppressing the rebellion and large-scale repression, the emperor centralized the administrative system, strengthened the military-bureaucratic apparatus, established a political police (Third Department of His Imperial Majesty's Own Chancellery) and also established strict censorship.

In 1826, a censorship statute was issued, nicknamed “cast iron”; according to it, it was forbidden to print almost anything that had a political background.

Autocracy of Nikolai Romanov

Some authors nicknamed him “the knight of autocracy.” He firmly and fiercely defended the foundations of the autocratic state and fiercely suppressed attempts to change the existing system. During the reign, persecution of the Old Believers resumed again.

On May 24, 1829, Nicholas the First Pavlovich was crowned in Warsaw as the king (tsar) of Poland. Under him, the Polish uprising of 1830-1831 was suppressed, during which he was declared dethroned by the rebels (Decree on the dethronement of Nicholas I). After the suppression of the uprising by the Kingdom of Poland, independence was lost, and the Sejm and the army were divided into provinces.

Meetings of commissions were held that were designed to alleviate the situation of serfs; a ban was introduced on killing and exiling peasants, selling them individually and without land, and assigning them to newly opened factories. Peasants received the right to own private property, as well as to redeem from the estates being sold.

A reform of state village management was carried out and a “decree on obligated peasants” was signed, which became the foundation for the abolition of serfdom. But these measures were belated and during the tsar’s lifetime the liberation of the peasants did not occur.

The first railways appeared in Russia (since 1837). From some sources it is known that the emperor became acquainted with steam locomotives at the age of 19 during a trip to England in 1816. He became the first Russian fireman and the first Russian to ride on a steam locomotive.

Property guardianship over state-owned peasants and the status of obligated peasants were introduced (laws of 1837–1841 and 1842), and codification was carried out Russian laws(1833), stabilization of the ruble (1839), under him new schools were founded - technical, military and general education.

In September 1826, the emperor received Pushkin, who had been released from Mikhailovsky exile, and listened to his confession that on December 14, Alexander Sergeevich was with the conspirators. Then he dealt with him like this: he freed the poet from general censorship (he decided to personally censor his works), instructed Pushkin to prepare a note “On Public Education,” and called him after the meeting “ the smartest person Russia."

However, the tsar never trusted the poet, seeing him as a dangerous “leader of the liberals”; the great poet was under police surveillance. In 1834, Pushkin was appointed chamberlain of his court, and the role played by Nikolai in the conflict between Pushkin and Dantes is assessed by historians as quite contradictory. There are versions that the tsar sympathized with Pushkin’s wife and set up the fatal duel. After the death of A.S. Pushkin was assigned a pension to his widow and children, but the tsar tried in every possible way to limit the memory of him.

He also doomed Polezhaev, who was arrested for his free poetry, to years of soldiery, and twice ordered M. Lermontov to be exiled to the Caucasus. By his order, the magazines “Telescope”, “European”, “Moscow Telegraph” were closed.

Significantly expanded Russian territory after the wars with Persia (1826–

1828) and Turkey (1828–1829), although the attempt to make the Black Sea an internal Russian sea met active resistance from the great powers, led by Great Britain. According to the Unkar-Iskelesi Treaty of 1833, Türkiye was obliged to close at the request of Russia Black Sea straits(Bosphorus and Dardanelles) for foreign military vessels (the treaty was canceled in 1841). Russia's military successes caused a negative reaction in the West because world powers were not interested in Russia's strengthening.

The Tsar wanted to intervene in the internal affairs of France and Belgium after the revolutions of 1830, but the Polish uprising prevented the implementation of his plans. After the suppression of the Polish uprising, many provisions of the Polish Constitution of 1815 were repealed.

He took part in the defeat of the Hungarian revolution of 1848–1849. An attempt by Russia, ousted from the markets of the Middle East by France and England, to restore its position in this region led to a clash of powers in the Middle East, which resulted in the Crimean War (1853–1856). In 1854, England and France entered the war on the side of Turkey. The Russian army suffered a series of defeats from its former allies and was unable to provide assistance to the besieged fortress city of Sevastopol. At the beginning of 1856, following the results of the Crimean War, the Paris Peace Treaty was signed; the most difficult condition for Russia was the neutralization of the Black Sea, i.e. prohibition to have naval forces, arsenals and fortresses here. Russia became vulnerable from the sea and lost the opportunity to conduct an active foreign policy in this region.

During his reign, Russia participated in the following wars: Caucasian War 1817-1864, Russian-Persian War 1826-1828, Russian-Turkish War 1828-29, Crimean War 1853-56.

The Tsar received the popular nickname “Nikolai Palkin” because as a child he beat his comrades with a stick. In historiography, this nickname was established after the story of L.N. Tolstoy "After the Ball".

Death of Tsar Nicholas 1

Died suddenly on February 18 (March 2), 1855 at the height of the Crimean War; According to the most common version, it was from transient pneumonia (he caught a cold shortly before his death while attending a military parade in a light uniform) or influenza. The emperor forbade performing an autopsy on himself and embalming his body.

There is a version that the king committed suicide by drinking poison due to defeats in the Crimean War. After his death, the Russian throne was inherited by his son, Alexander II.

He was married once in 1817 to Princess Charlotte of Prussia, daughter of Frederick William III, who received the name Alexandra Feodorovna after converting to Orthodoxy. They had children:

- Alexander II (1818-1881)

- Maria (08/06/1819-02/09/1876), was married to the Duke of Leuchtenberg and Count Stroganov.

- Olga (08/30/1822 - 10/18/1892), was married to the King of Württemberg.

- Alexandra (06/12/1825 - 07/29/1844), married to the Prince of Hesse-Kassel

- Konstantin (1827-1892)

- Nicholas (1831-1891)

- Mikhail (1832-1909)

Personal qualities of Nikolai Romanov

He led an ascetic and healthy lifestyle. Was an Orthodox believer  a Christian, he did not smoke and did not like smokers, did not drink strong drinks, walked a lot and did drill exercises with weapons. He was distinguished by his remarkable memory and great capacity for work. Archbishop Innocent wrote about him: “He was... such a crown-bearer, for whom the royal throne served not as a head to rest, but as an incentive to incessant work.” According to the memoirs of Her Imperial Majesty's maid of honor, Mrs. Anna Tyutcheva, her favorite phrase was: “I work like a slave in the galleys.”

a Christian, he did not smoke and did not like smokers, did not drink strong drinks, walked a lot and did drill exercises with weapons. He was distinguished by his remarkable memory and great capacity for work. Archbishop Innocent wrote about him: “He was... such a crown-bearer, for whom the royal throne served not as a head to rest, but as an incentive to incessant work.” According to the memoirs of Her Imperial Majesty's maid of honor, Mrs. Anna Tyutcheva, her favorite phrase was: “I work like a slave in the galleys.”

The king's love for justice and order was well known. I personally visited military formations, inspected fortifications, educational institutions, and government institutions. He always gave specific advice to correct the situation.

He had a pronounced ability to form a team of talented, creatively gifted people. The employees of Nicholas I Pavlovich were the Minister of Public Education Count S. S. Uvarov, the commander Field Marshal His Serene Highness Prince I. F. Paskevich, the Minister of Finance Count E. F. Kankrin, the Minister of State Property Count P. D. Kiselev and others.

The king's height was 205 cm.

All historians agree on one thing: the tsar was undoubtedly a prominent figure among the rulers-emperors of Russia.

E. Vernet "Portrait of Nicholas I"

According to the description of contemporaries, Nicholas I was “a soldier by vocation,

a soldier by education, by appearance and by inside.”

Personality

Nicholas, the third son of Emperor Paul I and Empress Maria Feodorovna, was born on June 25, 1796 - a few months before the accession of Grand Duke Pavel Petrovich to the throne.

Since the eldest son Alexander was considered the crown prince, and his successor Konstantin, the younger brothers - Nicholas and Mikhail - were not prepared for the throne, they were raised as grand dukes destined for military service.

A. Rokstuhl "Nicholas I in childhood"

From birth, he was in the care of his grandmother, Catherine II, and after her death, he was raised by a nanny, Scottish woman Lyon, to whom he was very attached.

Since November 1800, General M.I. Lamzdorf became the teacher of Nikolai and Mikhail. This was the choice of the father, Emperor Paul I, who said: “Just don’t make my sons such rakes as German princes.” Lamsdorf was the future emperor's tutor for 17 years. The future emperor did not show any success in his studies, with the exception of drawing. He studied painting as a child under the guidance of painters I.A. Akimov and V.K. Shebueva.

Nikolai realized his calling early. In his memoirs, he wrote: “The military sciences alone interested me passionately; in them alone I found consolation and a pleasant activity, similar to the disposition of my spirit.”

“His mind is not cultivated, his upbringing was careless,” Queen Victoria wrote about Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich in 1844.

During Patriotic War In 1812, he passionately wanted to participate in military events, but received a decisive refusal from the Empress Mother.

In 1816-1817 To complete his education, Nikolai made two trips: one throughout Russia (he visited more than 10 provinces), the other to England. There he became acquainted with the state structure of the country: he attended a meeting of the English Parliament, but remained indifferent to what he saw, because... believed that such a political system was unacceptable for Russia.

In 1817, Nicholas's wedding took place with the Prussian princess Charlotte (in Orthodoxy, Alexandra Fedorovna).

Before ascending the throne, his public activities were limited to the command of a guards brigade, then a division; from 1817, he held the honorary position of inspector general for the military engineering department. Already during this period military service Nikolai began to show concern for military educational institutions. On his initiative, they began to function in engineering troops company and battalion schools, and in 1818 The Main Engineering School (the future Nikolaev Engineering Academy) and the School of Guards Ensigns (later the Nikolaev Cavalry School) were established.

Beginning of reign

Nicholas had to ascend the throne under exceptional circumstances. After the death of childless Alexander I in 1825, according to the Decree on Succession to the Throne, Constantine was to become the next king. But back in 1822, Constantine signed a written abdication of the throne.

D. Doe "Portrait of Nicholas I"

On November 27, 1825, having received news of the death of Alexander I, Nicholas swore allegiance to the new emperor Constantine, who was in Warsaw at that time; swore in the generals, army regiments, and government agencies. Meanwhile, Constantine, having received news of his brother's death, confirmed his reluctance to take the throne and swore allegiance to Nicholas as the Russian Emperor and swore in Poland. And only when Constantine twice confirmed his abdication, Nicholas agreed to reign. While there was correspondence between Nicholas and Constantine, there was a virtual interregnum. In order not to drag out the situation for a long time, Nicholas decided to take the oath of office on December 14, 1825.

This short interregnum was taken advantage of by members of the Northern Society - supporters of a constitutional monarchy, who, with the demands laid down in their program, brought military units to the Senate Square that refused to swear allegiance to Nicholas.

K. Kolman "Revolt of the Decembrists"

The new emperor dispersed the troops from Senate Square with grapeshot, and then personally supervised the investigation, as a result of which five leaders of the uprising were hanged, 120 people were sent to hard labor and exile; The regiments that took part in the uprising were disbanded, the rank and file were punished with spitzrutens and sent to remote garrisons.

Domestic policy

Nicholas's reign took place during a period of aggravated crisis of the feudal-serf system in Russia, a growing peasant movement in Poland and the Caucasus, bourgeois revolutions V Western Europe and as a consequence of these revolutions - the formation of bourgeois revolutionary movements in the ranks of the Russian nobility and the common intelligentsia. Therefore, the Decembrist cause was of great importance and was reflected in the public mood of that time. In the heat of revelations, the tsar called the Decembrists “his friends of December 14th” and understood well that their demands had a place in Russian reality and the order in Russia required reforms.

Upon ascending the throne, Nicholas, being unprepared, did not have a definite idea of what he would like to see the Russian Empire. He was only confident that the country’s prosperity could be ensured exclusively through strict order, strict fulfillment of everyone’s duties, control and regulation of social activities. Despite his reputation as a narrow-minded martinet, he brought some revival to the life of the country after the gloomy last years of the reign of Alexander I. He sought to eliminate abuses, restore law and order, and carry out reforms. The Emperor personally inspected government institutions, condemning red tape and corruption.

Wanting to strengthen the existing political system and not trusting the apparatus of officials, Nicholas I significantly expanded the functions of His Majesty’s Own Chancellery, which practically replaced the highest state bodies. For this purpose, six departments were formed: the first dealt with personnel issues and monitored the execution of the highest orders; The second was concerned with the codification of laws; The third monitored law and order in government and public life, and later turned into a body of political investigation; The fourth was in charge of charitable and women's educational institutions; The fifth developed the reform of state peasants and monitored its implementation; The sixth was preparing governance reform in the Caucasus.

V. Golike "Nicholas I"

The emperor loved to create numerous secret committees and commissions. One of the first such committees was the “Committee of December 6, 1826.” Nicholas set him the task of reviewing all the papers of Alexander I and determining “what is good now, what cannot be left and what can be replaced with.” After working for four years, the committee proposed a number of projects for the transformation of central and provincial institutions. These proposals, with the approval of the emperor, were submitted for consideration to the State Council, but events in Poland, Belgium and France forced the king to close the committee and completely abandon fundamental reforms. political system. So the first attempt to implement at least some reforms in Russia ended in failure, the country continued to strengthen clerical and administrative methods of management.

In the first years of his reign, Nicholas I surrounded himself with major statesmen, thanks to whom it was possible to solve a number of major tasks that were not completed by his predecessors. So, M.M. He instructed Speransky to codify Russian law, for which all laws adopted after 1649 were identified in the archives and arranged in chronological order, which were published in 1830 in the 51st volume of the “Complete Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire”.

Then the preparation of the current laws began, drawn up in 15 volumes. In January 1833, the “Code of Laws” was approved by the State Council, and Nicholas I, who was present at the meeting, having removed the Order of A. the First-Called from himself, awarded it to M.M. Speransky. The main advantage of this “Code” was the reduction of chaos in management and arbitrariness of officials. However, this over-centralization of power did not lead to positive results. Not trusting the public, the emperor expanded the number of ministries and departments that created their local bodies in order to control all areas of life, which led to the swelling of the bureaucracy and red tape, and the costs of their maintenance and the army absorbed almost all state funds. V. Yu Klyuchevsky wrote that under Nicholas I in Russia “the building of the Russian bureaucracy was completed.”

Peasant question

The most important issue domestic policy Nicholas I was faced with the peasant question. Nicholas I understood the need to abolish serfdom, but could not carry it out due to opposition from the nobility and fear of a “general upheaval.” Because of this, he limited himself to such minor measures as the publication of a law on obligated peasants and the partial implementation of the reform of state peasants. The complete liberation of the peasants did not take place during the life of the emperor.

But some historians, in particular V. Klyuchevsky, pointed to three significant changes in this area that occurred during the reign of Nicholas I:

— there was a sharp reduction in the number of serfs, they ceased to constitute the majority of the population. Obviously, a significant role was played by the cessation of the practice of “distributing” state peasants to landowners along with lands, which flourished under the previous kings, and the spontaneous liberation of the peasants that began;

- the situation of state peasants greatly improved, all state peasants were allocated their own plots of land and forest plots, and auxiliary cash desks and grain stores were established everywhere, which provided assistance to the peasants with cash loans and grain in case of crop failure. As a result of these measures, not only did the welfare of state peasants increase, but also treasury income from them increased by 15-20%, tax arrears were halved, and by the mid-1850s there were practically no landless farm laborers eking out a miserable and dependent existence, all received land from the state;

- the situation of serfs improved significantly: a number of laws were adopted that improved their situation: landowners were strictly forbidden to sell peasants (without land) and send them to hard labor, which had previously been common practice; serfs received the right to own land, entrepreneurial activity and received relative freedom of movement.

Restoration of Moscow after the Patriotic War of 1812

During the reign of Nicholas I, the restoration of Moscow after the fire of 1812 was completed; on his instructions, in memory of Emperor Alexander I, who “restored Moscow from the ashes and ruins,” the Triumphal Gate was built in 1826. and work began on the implementation of a new program for planning and development of Moscow (architects M.D. Bykovsky, K.A. Ton).

The boundaries of the city center and adjacent streets were expanded, Kremlin monuments were restored, including the Arsenal, along the walls of which trophies of 1812 were placed - guns (875 in total) captured from the “Great Army”; the building of the Armory Chamber was built (1844-51). In 1839, the solemn ceremony of laying the foundation of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior took place. The main building in Moscow under Emperor Nicholas I is the Grand Kremlin Palace, the consecration of which took place on April 3, 1849 in the presence of the sovereign and the entire imperial family.

The improvement of the city’s water supply was facilitated by the construction of the “Alekseevsky water supply building,” founded in 1828. In 1829, the permanent Moskvoretsky Bridge was erected “on stone piers and abutments.” The construction of the Nikolaevskaya railway (St. Petersburg - Moscow; train traffic began in 1851) and St. Petersburg - Warsaw was of great importance for Moscow. 100 ships were launched.

Foreign policy

Important side foreign policy was a return to the principles Holy Alliance. Russia's role in the fight against any manifestations of the “spirit of change” in European life has increased. It was during the reign of Nicholas I that Russia received the unflattering nickname of “the gendarme of Europe.”

In the fall of 1831, Russian troops brutally suppressed the uprising in Poland, as a result of which Poland lost its autonomy. The Russian army suppressed the revolution in Hungary.

The Eastern Question occupied a special place in the foreign policy of Nicholas I.

Russia under Nicholas I abandoned plans for the division of the Ottoman Empire, which were discussed under the previous tsars (Catherine II and Paul I), and began to pursue a completely different policy in the Balkans - a policy of protecting the Orthodox population and ensuring its religious and civil rights, up to political independence .

Along with this, Russia sought to ensure its influence in the Balkans and the possibility of unhindered navigation in the straits (Bosporus and Dardanelles).

During the Russian-Turkish wars of 1806-1812. and 1828-1829, Russia achieved great success in implementing this policy. At the request of Russia, which declared itself the patroness of all Christian subjects of the Sultan, the Sultan was forced to recognize the freedom and independence of Greece and the broad autonomy of Serbia (1830); According to the Treaty of Unkar-Iskelesiki (1833), which marked the peak of Russian influence in Constantinople, Russia received the right to block the passage of foreign ships into the Black Sea (which it lost in 1841). The same reasons: the support of Orthodox Christians of the Ottoman Empire and disagreements over the Eastern Question - pushed Russia to aggravate relations with Turkey in 1853, which resulted in its declaration of war on Russia. The beginning of the war with Turkey in 1853 was marked by the brilliant victory of the Russian fleet under the command of Admiral P. S. Nakhimov, which defeated the enemy in Sinop Bay. This was the last major battle of the sailing fleet.

Russia's military successes caused a negative reaction in the West. The leading world powers were not interested in strengthening Russia at the expense of the decrepit Ottoman Empire. This created the basis for a military alliance between England and France. Nicholas I's miscalculation in assessing the internal political situation in England, France and Austria led to the country finding itself in political isolation. In 1854, England and France entered the war on the side of Turkey. Due to Russia's technical backwardness, it was difficult to resist these European powers. The main military operations took place in Crimea. In October 1854, the Allies besieged Sevastopol. The Russian army suffered a number of defeats and was unable to provide assistance to the besieged fortress city. Despite heroic defense city, after an 11-month siege, in August 1855, the defenders of Sevastopol were forced to surrender the city. At the beginning of 1856, following the Crimean War, the Paris Peace Treaty was signed. According to its terms, Russia was prohibited from having naval forces, arsenals and fortresses in the Black Sea. Russia became vulnerable from the sea and lost the opportunity to conduct an active foreign policy in this region.

Carried away by reviews and parades, Nicholas I was late with the technical re-equipment of the army. Military failures occurred to a large extent due to the lack of roads and railways. It was during the war years that he finally became convinced that the state apparatus he himself had created was good for nothing.

Culture

Nicholas I suppressed the slightest manifestations of freethinking. He introduced censorship. It was forbidden to print almost anything that had any political overtones. Although he freed Pushkin from general censorship, he himself subjected his works to personal censorship. “There is a lot of ensign in him and a little of Peter the Great,” Pushkin wrote about Nicholas in his diary on May 21, 1834; at the same time, the diary also notes “sensible” comments on “The History of Pugachev” (the sovereign edited it and lent Pushkin 20 thousand rubles), ease of use and good language king Nikolai arrested and sent to soldiery for Polezhaev’s free poetry, and twice ordered Lermontov to be exiled to the Caucasus. By his order, the magazines “European”, “Moscow Telegraph”, “Telescope” were closed, P. Chaadaev and his publisher were persecuted, and F. Schiller was banned from publication in Russia. But at the same time, he supported the Alexandria Theater, both Pushkin and Gogol read their works to him, he was the first to support the talent of L. Tolstoy, he had enough literary taste and civic courage to defend “The Inspector General” and after the first performance to say: “Everyone got it - and most of all ME.”

But the attitude of his contemporaries towards him was quite contradictory.

CM. Soloviev wrote: “He would like to cut off all the heads that rose above the general level.”

N.V. Gogol recalled that Nicholas I, with his arrival in Moscow during the horrors of the cholera epidemic, showed a desire to uplift and encourage the fallen - “a trait that hardly any of the crown bearers showed.”

Herzen, who from his youth was painfully worried about the failure of the Decembrist uprising, attributed cruelty, rudeness, vindictiveness, intolerance to “free-thinking” to the tsar’s personality, and accused him of following a reactionary course of domestic policy.

I. L. Solonevich wrote that Nicholas I was, like Alexander Nevsky and Ivan III, a true “sovereign master,” with “a master’s eye and a master’s calculation.”

“Nikolai Pavlovich’s contemporaries did not “idolize” him, as was customary to say during his reign, but were afraid of him. Non-worship, non-worship would probably be recognized as a state crime. And gradually this custom-made feeling, a necessary guarantee of personal safety, entered the flesh and blood of his contemporaries and was then instilled in their children and grandchildren (N.E. Wrangel).

Now about his two other sons - Konstantin and Nikolai and their two branches - "Konstantinovichi" and "Nikolaevich". Both had two marriages, like their brother Emperor Alexander II, but both Constantine and Nicholas had their second marriages to ballerinas.

Nikolai Nikolaevich (1831-1891) and Konstantin Nikolaevich (1827-1892)

Moreover, Nikolai did not register his second marriage, but cohabited without divorcing his first wife, who, by the way, became a saint. More on this later, but now a little about the three daughters of Nicholas I - Olga, Maria, Alexandra.

Olga Nikolaevna (1822-1892) Maria Nikolaevna (1819-1876) Alexandra Nikolaevna (1825-1844)

Maria Nikolaevna

(August 18, 1819 - February 21, 1876) - the first mistress of the Mariinsky Palace in St. Petersburg, president of the Imperial Academy of Arts in 1852-1876. She was the eldest daughter and second child in the family of Grand Duke Nikolai Pavlovich and Grand Duchess Alexandra Feodorovna. Unlike many princesses of that time, whose marriages were concluded for dynastic reasons, Maria Nikolaevna married for love. Married: Duchess of Leuchtenberg. Despite Maximilian's origins and his religion (he was a Catholic), Nicholas I agreed to marry his daughter with him, provided that the couple would live in Russia and not abroad.

The wedding took place on July 2, 1839 and took place according to two rites: Orthodox and Catholic. By decree of July 2 (14), 1839, the emperor granted Maximilian the title of His Imperial Highness, and by decree of December 6 (18), 1852, he bestowed the title and surname of Prince Romanovsky on the descendants of Maximilian and Maria Nikolaevna. The children of Maximilian and Maria Nikolaevna were baptized into Orthodoxy and raised at the court of Nicholas I; later Emperor Alexander II included them in the Russian Imperial family. From this marriage, Maria Nikolaevna had 7 children: Alexandra, Maria, Nikolay, Evgenia, Evgeny, Sergey, Georgy.