Why do words alternate sounds? This occurs during the formation of grammatical forms of words. That is, sounds in the same morpheme, for example in a root, can replace each other. This replacement is called alternation. Let us note right away that we will talk about phonetic processes, and not about spelling words.

In certain cases, not only vowel sounds alternate, but also consonants. Most often, alternation is found in roots, suffixes and prefixes.

Moss - moss, carry - carry, cool - cooler, friend - friends - be friends - at the root of the word;

circle - mug, daughter - daughters, winter - winter, valuable - valuable - in suffixes;

wait - wait, call - convene, rub - rub - in prefixes.

There are two types of alternations: historical (they cannot be explained, they arose a long time ago and are associated with the loss of vowel sounds [ъ], [ь] (сънъ - съна, сть - to flatter) or with the inexplicable identity of consonant sounds (run - run) and phonetic ( positional in a different way, since they depend on the position of the sound in the word [nΛga - nok], they can be explained from the point of view of the modern Russian language, for example, the alternation [g//k] arose because the consonant sound is preserved before the vowel, and in at the end of the word the sound is deafened and changes its sound quality).

Historical alternations

|

Vowel sounds |

|

|

moss - moss root - root tan - tan freeze - freeze breathe - sigh carry - carry understand - understand - understand sound - ringing |

|

|

Consonants |

|

|

[p//pl; m//ml; b//bl; v//vl] [sk//st//sch] |

buy - buy, earthly - earth wear - wear carry - drive dry - dry land leads - lead father - fatherland shine - sparkle - shines light - candle - lighting fence - fence - fencing hail - cry - exclamation |

Phonetic (positional) alternations

|

Vowel sounds |

|

|

[o//i e //b] [a//i e //b] [e//i e//b] |

V [O] day - in [Λ ]yes - in [ъ] dyanoy tr [A] vka - tr [Λ] va - tr [ъ]withered n [O] s - n [And uh ] set - n [b] suny P [A] t - p [And uh ] type [b]titenth With [e] m - s [And uh ] mi - s [b] mid-tenth |

|

vowel sounds |

|

|

voiced - voiceless hard - soft |

But [and] and - but [w] mo[ l]- mo [l’]ь |

Historical alternations are revealed during word formation and form change.

Phonetic (positional) can be determined by the reduction of vowels and assimilation of consonant sounds.

There are many fluent vowels when changing one-syllable and two-syllable nouns according to cases [o, e, and// -]:

mouth - mouth, ice - ice, stump - stump;

fire - fire, knot - knot, wind - wind, lesson - lesson, nail - nail, hive - hive;

bucket - buckets, window - windows, needle - needles, egg - eggs.

There are also fluent vowels in short adjectives:

short is short, bitter is bitter, funny is funny, long is long, cunning is cunning.

In the roots of different types of verbs, alternations of vowels and consonants also occur:

touch - touch, inspect - inspect, collect - collect, send - send, light - light, understand - understand, squeeze - squeeze.

It is important to know the alternation of sounds in order to correctly apply spelling rules when difficulties arise with writing letters in different parts of speech. If you don’t recognize the alternation, you can make a mistake when morphemic parsing when you highlight parts of a word.

Alternation of sounds- this is a natural difference in sounds in variants of the same morpheme.

Alternation of stressed vowels. Soft consonants cause the vowel articulation to shift forward and upward. In transcription, this shift in the initial and final phase of the vowel is indicated by dots above the letter: /ch¢ac/, /ma ¢t/.

Between soft consonants there is a shift forward and upward in the central part of the vowel: /h ast/ and /h as/, /mel/ and /m el/ - vowel – E of the front row moves (forward) upward. /pike/ and /pike/.

We see that the alternation of vowels under stress after soft and before soft consonants occurs in their significatively strong position, but they are different perceptually.

Hard consonants before and after /A, O, E, U/ have no effect on the vowel: /jaguar, gift, yes/ - the same sound is everywhere /A/ - the environment does not affect the sound - this is a perceptually strong position for /A,O,E,U/ and weak for /I/; position after soft.

In a weak position, sounds adjacent to a consonant adapt the vowel to their articulation. This can be detected by ear. In the word mass it is pronounced /A/, the position here is strong. In the word meat, it is pronounced /A/ - the sound is extraordinary throughout its sound - it is more advanced. In the word /Ira/ it is pronounced /I/ - this is the main variant of the phoneme /I/, the quality of the sound is not determined by position. In the word /cheese/ - it is pronounced /Y/, and then it is pronounced /I/: /sy-i-i-ra/.

Thus, in the perceptually weak position /A/ is the result of adaptation of /A/ to the preceding soft consonant, and in the same way /І/ is the result of adaptation of /I/ to the preceding hard one.

Alternation of unstressed vowels. Unstressed vowels differ from stressed vowels quantitatively and qualitatively: they are shorter than stressed vowels and are pronounced with less force and a different timbre. In connection with this distinction, stressed vowels are called vowels of full formation, unstressed vowels are called reduced vowels.

There is also a difference between unstressed vowels, which is due to their place in relation to stress and position in the syllable.

Potebnya proposed a formula that conditionally estimates the strength of stressed and unstressed syllables in units of 3,2,1. Strike 3, 1st pre-strike - 2, others - 1. /b isLradak/ - disorder, /per i padgLtofk/.

The strength of an unstressed vowel depends on the following conditions: 1. an open syllable is equal to the 1st pre-stressed one: attack /LtkLvat/, aist/aist/.

The strength of an overstressed final open syllable fluctuates by 1 and 2 units: cap / capkL / \ reduced vowels of the 1st degree (2 units of stress) and a vowel of the 2nd degree, (1 unit) - b and L.

Qualitative differences between stressed and unstressed vowels are due to the fact that unstressed vowels are articulated less energetically than stressed ones. The body of the tongue occupies a position close to neutral. Unstressed /И/ /ы/ are vowels of the upper rise: the tongue does not reach the upper position: /vitrinj/, /sy ry/.

When pronouncing the vowel A in the 1st pre-stressed syllable, the tongue does not reach the extreme lower position, its more accurate representation is L: /trLva/, in the 2nd pre-stressed syllable the sound A corresponds to /Ъ/ - the tongue occupies the middle position: /нъпLдат/ .

What is called positional alternation of sound units? When can we say that sound units alternate positionally?

We will start from the concept of alternation. Alternation is always found in the composition of a specific morpheme. If the same morpheme in different words (or in different forms of one word) has a partially different sound composition, then alternation is evident. Twist - I twist. Forms of one verb, they have one root; its meaning in these two forms is the same; the sound composition is also partially the same: there is a common part kru-, but the last sound of this root is in one form [t’], in another [h’]. This is alternation.

The radically steep/steep alternation is reflected in the letter. But there are alternations that are not reflected in the spelling of words. For example, spelling does not reflect the alternation in the forms of words moro[s] - moro[z]y; but it’s still an alternation.

Position is the condition for pronouncing sounds. There are, for example, the following positions: vowels - under stress, in an unstressed syllable after a soft consonant, before [l], before a pause, consonants - at the end of a word, before [e], before a soft dental, after a sonorant consonant. Each sound in a word is in some position.

Some alternations are determined by position, and they are called positional. For example, exchange

[z] to [s] occurs at the end of a word before a pause. Indeed: moro [z] y - moro [s], rasska [z] y -

story[s], ro[z]a - ro[s1, va[z]a - va[s]; black eye [z] a - black eye [s], plague [z] y - plague [s], si [z] y - si [s]; pogrya [z] la - pogrya [s], froze [z] la - froze [s], oble [z\li - oble [s], manager of household [z'] food - manager [s], Kama auto [z ] avod - Kama [s], higher educational [institution] - university\s]. There is no word, no word form in which [z], coming to the end of the word, would not be replaced by a voiceless [s].

In itself, from a purely acoustic or articulatory point of view, a pause does not at all require that the noisy consonant before it be voiceless. There are many languages (Ukrainian, Serbo-Croatian, French, English) where the final noisy remains voiced. The alternation is determined not by the acoustic or articulatory nature of sound, but by the laws of a given language.

On what basis do we conclude that alternation is positional? Perhaps we take into account the articulatory and acoustic clarity of the interaction of sounds? For example, a tooth before a soft tooth must itself be soft (in Russian literary language), cf.: tail - tail [s’] quieter, bush - ku [s’] thick, let go - let go [s’] tit, etc.

But the opinion about the need for a visually obvious likening of sounds to each other is incorrect. In order to recognize the pattern of positional alternation, sound similarity is not necessary. How special case it is possible, but precisely as a private one. There are cases when phonetic alternation is alive, active, positional, but there is no similarity between the sounds that interact.

Example. In the Russian literary language [o] (stressed vowel) in the first pre-stressed syllable after a hard consonant is replaced by the vowel [a]: new - newer, house - at home, stand - stand, etc. Alternation is positional. However, there is no acoustic need for such alternation. It cannot even be said that [o] is replaced in an unstressed syllable by the sound [a], because [a] is articulatory weaker than [o] (this would explain why it is appropriate to have [a] in weak unstressed syllables). On the contrary, [a] requires a larger solution oral cavity, i.e. more energetic articulation.

In general, to imagine (as a general law) the reason for sound alternation is that one sound requires the acoustic or articulatory adaptation of another sound to itself is a big misconception. So, it is impossible to guess from the acoustic-articulatory essence of the sounds that the position requires a certain alternation.

By what reliable criterion can we separate positional alternations from non-positional ones? Just one thing at a time: positional alternations know no exceptions. If position N2 appears instead of N1, then the sound a always changes to the sound P; It is natural to consider position N2 as the reason for the exchange.

On the contrary, if the position N2 in some words is accompanied by the appearance of p (instead of a), and in others it is not accompanied (but remains without replacement), then the position N2 cannot be considered as the reason for its alternation|| R. She does not condition him. Therefore, an alternation that knows an exception is not positional.

Consequently, positional alternation can be explained in two ways: it is an alternation that occurs in a given language system without exception; it is an alternation conditioned by position. Both definitions are identical in essence.

Different sounds that have completely different characteristics can be in positional alternation. For example, they alternate [o] (middle vowel, back row, labialized) and [a] (low vowel, middle row, non-labialized). Significant qualitative differences do not prevent them from being alternating sounds (Table 4):

Table 4

Examples

Position

Members

alternation

At home, newer, standing

Stressed syllable

First prestressed syllable after a hard consonant

There are no exceptions, that is, there are no cases (among the commonly used full-valued words of the Russian literary language) when the vowel [o] would be preserved in the second position, therefore, the alternation is positional.

The sound can alternate with zero (Table 5):

Table 5

| Position | Members alternation | Examples |

| Before the pause | 1i] | stop, build, hero, yours |

| After a vowel before a vowel | zero | stands, builds |

| nym [and] | heroes, their | |

A phoneme is the minimum segmental unit of language that serves to distinguish significant units - morphemes. This is the main of the insignificant units of language.

A phoneme relates to the sound of speech as an invariant to a variant, that is, as an abstract unit to its concrete manifestations. Thus, the phoneme is the minimal unit of language, and sound is the minimal unit of speech.

The main function of the phoneme is meaningful. Compare words table And chair, mom, lama And frame- how do we understand that in each group we have different words? In each row, the words differ in sound only in one position: the first pair of words - with stressed vowels<о>And<у>, the second - initial consonants<м>, <л>, <р>. Consequently, these sounds perform a semantic-distinguishing function in the given words and represent different phonemes. Phonemes do not necessarily indicate differences between root morphemes. Compare words tear And not enough- they contain phonemes<а>And<э>prefixes are distinguished.

Now compare the following units: cat And k[a]ty (kty), sa[t] And gardens (With

yes). Before us are different forms of the same words. That is, different sounds occur in the same root morpheme (cat-, garden-), do not perform a meaningful function. This means that these sounds are part of one phoneme - they are its options. How then can we determine a phoneme, which sound: [o] or [a], [t] or [d] is “capital” for it? Need to determine strong position: for vowel phonemes this is the stressed position, therefore in word forms cat And cats phoneme is realized<о>. In a word cat it is presented in the main version, and in the word cats- in option [a] (more precisely,), since the sound [o]

in an unstressed position it undergoes a qualitative reduction. For consonants, the position before the vowel is strong, therefore, in the word gardens the main variant of the phoneme is implemented<д>,

and in the word garden it is represented by its variant [t], obtained as a result of deafening a voiced consonant at the end of a word.

Some linguists distinguish between variants and variations (or phoneme shades): variants are

those sounds representing a given phoneme that are the same as sounds representing another phoneme, for example, a sound may represent a phoneme<о>, and phoneme<а>. And the shade of the sound [o], by which it differs in words ox And led, does not change it qualitatively, we will not confuse the phoneme here<о>with a different phoneme. Therefore it is only a phoneme variation<о>. But this approach raises a number of questions, for example, if the sound is undoubtedly an option for the phoneme<о>, what it is for a phoneme<а>: option or variation? On the one hand, this sound is of high quality

no different from percussion sound[a], but, on the other hand, in this position the phoneme<а>matches

with the phoneme [o]. Therefore, we will not divide phoneme variants into those more or less close to the main one; what is important for us is precisely that there is a common linguistic unit and its specific implementations in speech.

The presence of different sounds in the same morpheme is calledalternating. In the case when different sounds are representatives of the same phoneme, we speak of positional alternations of sounds.

For example, in words five - five - patch the sound [a] in the stressed position alternates positionally

with the sound [i] with the shade [e] in the first pre-stressed position and with a super-short sound [b] in all other positions. All these sounds are variants of the phoneme<а>after soft consonants. It is generally accepted that phoneme in writing transmitted by letter. Indeed, if by the sound of the word cat And code coincide in the initial form, then in writing we can always distinguish them.

The phonemic composition of these words is written as follows:<к><о><т>, <к><о><д>.

But there are exceptions to this pattern. Hard and soft consonants are different phonemes: they distinguish words from each other, for example, small And crumpled, ox And led. These words differ precisely in consonant sounds, and in writing this is conveyed by the iotated vowels “ya” and “e”, which indicate the softness of the preceding consonant. Thus, in such cases, different consonant phonemes are not expressed by different consonant letters. There are also reverse exception- when one phoneme is transmitted in different letters. Remember the words with prefixes ending in “z” and “s”. In words disassemble And resettle the same phoneme<з>is represented by its different variants: [z] and [s]. This is exactly one phoneme, since in the position before the voiceless consonant all voiced consonants are deafened: pull up, tighten- in these words a voiceless consonant sound is pronounced, but a letter is written that denotes a voiced consonant phoneme! This means that in prefixes with “z” and “s” the phonemic principle of writing is violated

and gives way to phonetic, that is, the representation of a sound by a letter rather than a phoneme.

Hard and soft consonants can represent either separate phonemes or variations of the same phoneme (hard or soft). Let's take, for example, the words cats And kittens- one morpheme, meaning

she has one thing, but different phonemes! Why shouldn’t [t] and [t`] be considered variants of the phoneme here?<т>?

To distinguish phonemes, it is important to understand one pattern: the same phoneme in the same phonetic position is always realized by the same variant. If different sounds are observed in one position, therefore, we have different phonemes, since the difference

in sound is not determined by the position of the sound relative to other sounds, but is independent (or determined by the laws of another level). And in the word cats, and in the word kittens the sound [t] is found before non-front vowels (before vowels other than [e] and [i]). This position is absolutely strong for the consonant phoneme. Moreover, we can quote the words cat And kittens, where a hard and soft consonant are located before the same vowel [a]. Consequently, we have before us a phenomenon when sounds - representatives of different phonemes - occur in the same morpheme. In other words, before us phoneme alternation. And it is determined by the morphological (morpheme) position - the suffix denoting young, which always requires softening the last consonant of the generating stem, compare: elephant, But baby elephant, baby elephants; tiger, But tiger cubs.

And if we take word forms cat And about the cat- then we will have the phonetic positional alternation [t]/[t`], representing the phoneme<т>, since all hard consonants, paired in hardness - softness, are softened before the vowels [e] and [i], no matter what morpheme they are in.

If the positional alternation of sounds within one phoneme is determined precisely phonetic position(for the phonetic level it does not matter that there is a zero sound after a consonant

in a word garden refers to the ending, vowel [s] in a word gardens- also to the ending, and the vowel [o]

in a word little garden- to the suffix), then the alternation of phonemes is determined by the morphological (morphemic) position - that is, it becomes important which morpheme the environment of a given phoneme belongs to.

In the Russian language, such morphological alternations are quite common, expressing certain grammatical and word-formation meanings.

Thus, all variants of the same morpheme found in a language can be distinguished by two types of alternations: positional (they would be more accurately called phonetic-positional) and morphological (morpheme-positional). Both types of alternations can occur in the same word form. For example, in a series of word forms WHO, v`oz, cart, carry, I'm taking, carried, I drive, carries root WHO- presented in options 1) [voz], 2) [voz], 3) [v/\z], 4) [v/\z`], 5) [vis], 6) [v`os], 7) [v/\zh], 8) [voz`]. The first three of them contain only positional (phonetic) alternations: in word forms 1) and 2) the alternation of consonants [s] and [z] is presented as representatives of the phoneme<з>, in 2) and 3) - alternation of vowel sounds [o] and as representatives of the phoneme<о>depending on the stress. If we compare the main option - 2) - and option 8), then in this pair of words we will observe only morphological alternation: hard consonant phoneme<з>alternates with a soft phoneme<з`>before the suffix -And-, forming the verb stem. In all other word forms both alternations are presented: in 5) historical alternation of phonemes is observed

Morphological alternations in linguistics are often called historical, since they are related

with processes that previously led to the emergence of regular positional alternations,

and with the change in the phonetic system of the language they remained in the form of alternating phonemes.

Positional alternations of vowels. qualitative and quantitative reduction

So, we know that vowel phonemes are represented by their basic variant only under stress. In an unstressed position, the sound of vowels changes according to a regular pattern: the reduction (that is, shortening) of vowels depends on the position of the vowel relative to the place of stress. There are strong positions (stressed) and weak ones: I weak position is I pre-stressed (that is, the vowel in the syllable preceding the stressed one) and the absolute beginning of the word (only for words starting with a vowel, for example, apricot), II weak position is any post-stressed position and pre-stressed positions that are more than one syllable away from the stress point (except for the absolute beginning of the word).

Each phoneme is always represented in the same position by the same variant. In addition to the place relative to the stressed syllable, the choice of variant of the vowel phoneme is also determined by the hardness - softness of the preceding consonant, and for the phoneme<о>The condition of being after a sibilant consonant is also important.

The table shows regular positional alternations of vowel sounds in the Russian language.

| Strong position (under stress) | I weak position (1st syllable before the stressed and absolute beginning of the word) | II weak position (all others) |

| a (s[a]d, p[`a]t) | /\ after a hard consonant, сд$\textrm(и)^\textrm(е)$ after a soft consonant р[$\textrm(и)^\textrm(е)$]ti | ъ after a solid (with[ъ]argument), ь after soft (p[b]barrow) |

| o (d[o]m, l[`o]d, sh[o]lk) | /\ after a hard consonant (dma), $\textrm(s)^\textrm(e)$ after a hard hissing consonant (w[$\textrm(s)^\textrm(e)$ ]lka), $\textrm( i)^\textrm(e)$ after a soft consonant (l[$\textrm(i)^\textrm(e)$]doc) | ъ after hard consonants (d[ъ]movoy, sh[ъ]lkopryad), ь after soft (l[l]dorub) |

| e (six, forest) | $\textrm(ы)^\textrm(е)$ after hard consonants (ш[$\textrm(ы)^\textrm(е)$]stay), $\textrm(и)^\textrm(е)$ after soft consonant (l[$\textrm(i)^\textrm(e)$]snoy) | ъ after hard consonants (sh[ъ]tipal), ь after soft (l[l]sostep) |

| and (feast) | and short (p[$\check(\textrm(s))$]horn) | and short (p[$\check(\textrm(s))$]horn) |

|

s (dampness, wider [wide])* |

ы short (with[$\check(\textrm(s))$ ]roy, sh[ $\check(\textrm(s))$ ]roky) | ы short (with[$\check(\textrm(s))$ ]shaggy, sh[ $\check(\textrm(s))$ ]rina) |

| y (miracle) | y short (h[$\check(\textrm(y))$]gingival) | y short (ch[$\check(\textrm(y))$]desa) |

*Note. The vowel [s] after hard hissing consonants that have no pair for softness,

According to the tradition of Russian graphics, it is conveyed by the letter “i”. In general, writing vowels after

sibilant consonants and “ts” (which in the history of the language were initially soft, but later hardened)

does not obey any consistent rule and is purely traditional in nature.

positional consonant alternations

In the area of consonants in modern Russian, regular phonetic processes are also observed, leading to the emergence of phoneme variants. They are most clearly presented in connection with such quality of consonants as voicedness - deafness. Three processes are distinguished, as a result of which voiceless and voiced phonemes are neutralized (that is, they coincide).

Stun a voiced consonant at the end of a word. Compare pairs of words horn - rock, cat -code, flu - mushroom, roses And grew up. They are pronounced the same way, with a voiceless consonant at the end: [rock], [cat], [grip], [ros].

*Note. Words similar to the ones above - identical in sound, but different in spelling and meaning - are called homophones. Neutralization of different phonemes often leads to

to the emergence of homophones.

Which consonants, in your opinion, constitute an exception, that is, are not subject to deafening?

Since a voiced consonant passes into its voiceless “pair” at the end of a word, only consonants that are paired in deafness and voicedness are subject to this law, and unpaired voiced (sonorant) consonants do not change their pronunciation. Scrap And break, zero And zeros, thief And the thieves, dream And dreams- in the roots of these words the same sonorant consonants [m], [l`], [r], [n] are pronounced.

Combinations of consonants, one of which is voiced and the other is voiceless, are generally not characteristic of the Russian language. Therefore, in groups of consonants, there is an assimilation (assimilation) of the preceding to the subsequent in terms of voicing - deafness (deafening or voicing). This change in the sound of consonants is called regressive (that is, going from front to back) assimilation.

Assimilation (assimilation) consonants by deafness(deafening a voiced consonant before a voiceless one)

Compare words strip And cart, gait And rewind, soup And clove. In all these words, voiceless consonants are pronounced: [s] in the first pair of words (polo[s]ka - polo[s]ka),[t] - in the second (look[t]ka - move[t]ka),[p] - in the third (su[p]chik - tooth[p]chik), that is, and where they represent the corresponding phonemes<с>, <т>, <п>, and as representatives of voiced phonemes<з>, <д>, <б>(compare: carts, walk, teeth). Sometimes such deafening leads to the formation of homophones:

carry - lead, interspersed - mixed up.

Assimilation (assimilation) consonants by voicing (voicing voiceless consonant before a voiced one)

This process is somewhat less common than stunning.

Compare words thread And mowing, give away And give in- they are pronounced with voiced consonants [з`], [д].

Voicing of voiceless unpaired consonants leads to the formation of their non-phonemic voiced pairs:

[h] goes into [j`] (to save)[ts] - in [dz] (father gave)[sq] - in [zh`] (it was a vegetable).

Before sonorant consonants and [in] assimilation by deafness - voicing does not occur: Mark,

But mark[d]tag, [s]return, But expand.

Assimilation (assimilation) consonants can also occur by hardness - softness. Happens more often softening (assimilation by softness) hard consonants before soft ones. Not all consonants are equally susceptible to this process.

The most susceptible to softening are the dental [z], [s], [n], [p], [d], [t] and labial [b], [p], [m], [v], [f]. Place,

But about me[s`t`]e, student[nt], But about the student[n`t`]e, [dn]o, But o [`d`n]e.

As can be seen by last word, in the position before a soft consonant, neutralization of hard and soft consonant phonemes occurs, which sometimes leads to the formation homophones: word form about the day may belong to a lexeme day with soft phoneme<д`>, and the lexeme bottom

with hard phonemes<д>And<н>, positionally softened.

They do not soften before soft consonants [g], [k], [x], and also [l]: [g]look, [k]leit, [h]leb, po[l]net And

etc.

Labial consonants do not soften before soft dental ones: [n]ling, co[f]te, [m]fly, [in]take.

Assimilation of consonants by hardness is carried out at the junction of a root and a suffix beginning with a hard consonant: mo[r`]e - nautical, January[r`]b - January etc.

It can also happen complete assimilation of consonants- two consonants, different in place of formation, merge into one long consonant sound. Thus, sibilant consonants resemble the preceding sibilants: sew[$\overline(\textrm(ш))$ыт`], compress[$\overline(\textrm(zh))$at`], count[$\overline(\textrm(w`))$es`t`], split[ra$\overline(\textrm(ш`))$ $\textrm(i)^\textrm(e)$p`it`], as well as hissing [h] and [ts] liken to themselves the preceding [t] and [d]: report , in short[fkra$\overline(\textrm(ts))$ъ]. Sometimes there is only one sound in a group of consonants falls out, not pronounced. This happens with the consonants [t], [d]

(and sometimes also with consonants [l] and [v]) in combinations of several consonants between vowels. This simplification of consonant groups is consistently observed in the combinations “stn”, “zdn”, “stl”, “vstv”, “rdts”, “lnts”: local, late, happy, feeling, heart, sun.

Adaptation of the pronunciation of one sound to the pronunciation of another sound is called accommodation. There are three types of accommodation: progressive (when the articulation of a vowel adapts to the articulation of the preceding consonant: strap - [l "amk]), regressive (when the articulation of a vowel adapts to the articulation of the subsequent consonant: take - [brother"]) and progressive-regressive (when articulation vowel adapts to the articulation of both the preceding and subsequent soft consonant: sit - (s "at"]). In Russian, progressive accommodation is stronger. This is explained by the fact that in Russian the preceding consonant has the greatest influence on vowels, since the influence a consonant on a vowel within one syllable is much stronger than the influence of a consonant on another syllable.

During the transition from consonant articulation to vowel articulation, the speech organs do not have time to quickly change their position. Soft consonants can cause an upward shift in vowel articulation. For example, in the word meat - [m "as"], after a soft consonant you need to pronounce the sound [a]. When pronouncing a soft consonant [m"], the middle part of the back of the tongue is raised high. And to pronounce the vowel sound [a], the tongue must be quickly lowered, since it is a low vowel. Immediately the tongue does not have time to lower itself and lingers a little in the upper position, which is characteristic of the vowel [i]. Therefore, the sound [a] in this word in its first phase has a slight overtone, similar to |i], becomes more closed.

The vowel[s] after hard consonants experiences progressive accommodation, becoming a more posterior sound. This is because it is influenced by the articulation of the preceding hard consonant. When pronouncing hard consonants, the tongue occupies a more posterior position than when pronouncing the front vowel [i]. Under the influence of the articulation of a hard consonant, the adjacent front vowel [i] is moved back and the middle vowel [s] is pronounced instead: play - [igrat"] and play - [play"].

In the position between two soft consonants, all vowels become more closed, but low and middle vowels change more as a result of accommodation than high vowels.

The result of accommodation is positional alternation of vowels of two types.

Stressed vowels are pronounced clearly and never coincide in sound with other vowels. Only minor changes are possible, depending on the hardness or softness of adjacent consonant sounds. For example, front vowels under stress between soft consonants or at the beginning of a word before a soft consonant become more closed, narrow, tense sounds: shadows - [t"e"n"i", drank - [p"i"l"i", il - [and "l"]. Taking into account the above, the following positional alternations can be noted for front vowels under stress: [e]//[e"] 7 [i]/[i"].

But these alternations occur within one phoneme and do not perform a distinctive function in Russian.

Non-front vowels under stress are also represented by different shades within the same phoneme. After soft consonants, before hard consonants, sounds are pronounced that are advanced in excursion, and after hard consonants, before soft ones, sounds are pronounced forward in recursion. These shades of sounds are indicated by a dot at the top on the side of the sign where the adjacent soft consonant is located: crumpled - [m "al", mol - [mo "l"], led - [v" "ol", south - "uk].

Between soft consonants, non-front vowels are represented by shades advanced throughout the articulation. This is marked with two dots above the sign: hatches - [l"u"k"i], uncles - [d"a"d"i], Leni - [l"o"n"i].

Thus, for vowels of the non-front row under stress, depending on the proximity of hard or soft consonants, the following positional alternations can be noted: [a]\\a a a; o o o o; uuuu

Phonetic processes

Phonetic processes are changes in sounds that occur over time: one sound is replaced by another sound in the same position, but at a later time. Some phonetic processes are associated with the interaction of neighboring sounds (such sound processes are called combinatorial), others are determined by the position of the sound in the word and are not related to the influence of neighboring sounds (such sound processes are called positional).

Combinatorial ones include assimilation, dissimilation and simplification of consonant groups (dierez).

Positional deafening includes the deafening of voiced consonants at the end of a word ( law of the end of the word).

Assimilation- this is the likening of a sound to a neighboring sound. Assimilation is characterized by the following characteristics: 1) direction; 2) by result; 3) by position.

In terms of direction, assimilation is of two types: regressive and progressive. With regressive assimilation, the subsequent sound is similar to the previous one, for example, shop - [l afkъ]. The subsequent voiceless consonant [k] resembles the previous voiced consonant [v] and makes it voiceless - [f]. With progressive assimilation, the previous sound resembles the subsequent one. The modern Russian literary language is characterized by regressive assimilation; there are no examples of progressive assimilation in the literary language. Progressive assimilation can only be found in dialects and common speech, for example, in place of the literary Va[n"k]a they pronounce Va[n"k"]ya.

According to the result, assimilation can be complete or incomplete (partial). With complete assimilation, one sound is likened to another in all respects: 1) by the place of formation of the barrier, 2) by the method of formation of the barrier; 3) by the ratio of voice and noise; 4) in terms of hardness and softness. For example, give - o[dd]at - o[d]at. The voiceless consonant [t] becomes similar to the subsequent voiced consonant [d] and becomes voiced [d], merging in pronunciation into one long sound [d]. The remaining characteristics of the sounds [t] and [d] (by place of formation, by method of formation, by hardness) are the same. With incomplete assimilation, one sound is likened to another not according to all characteristics, but only according to some, for example, all - [fs "e]. This is incomplete assimilation, since the previous voiced consonant sound [v] is likened to the subsequent voiceless consonant sound [s 1 ] only in deafness. According to the method of formation, the sounds [v] and [s"] are both fricative, i.e. there is no need for assimilation. The sound [f] also remains fricative. There is no comparison in terms of other characteristics: 1) according to the place of formation - [f] labial, and [s"] anterior lingual; 2) in terms of hardness and softness - [f] hard, and [s"] soft.

According to position, assimilation can be contact or distant. During contact assimilation, the likened and likened sounds are located nearby, there are no other sounds between them, for example: low - n[sk]o. Literary language is characterized by contact assimilation. With distant assimilation, between the sounds being compared and the sounds being likened, there are other sounds (or sound). Examples of distant assimilation are found in dialects and common speech. For example, in the word highway, between the sounds [w] and [s] there is the sound [L].

Types of assimilation:

1. Assimilation by deafness. Paired voiced noisy consonants, being in front of deaf noisy consonants, become similar to them and also become deaf: booth - bu^tk]a, All- [fs"e]. This is regressive incomplete contact assimilation due to deafness.

2.

Assimilation by voicing. Paired deaf noisy consonants, being in front of voiced noisy consonants, become similar to them and become voiced: beat off - o[db"]yt, hand over - |zd]yt. This is a regressive incomplete contact assimilation according to

sonority.

Assimilation in terms of voicedness and deafness occurs within a phonetic word, i.e. it is also observed at the junction of a functional word with a significant word: from the mountain - [z g]ory (assimilation by voicing), from the park - i[s p]ark (assimilation by deafness).

Consonants [в], [в"] in front of deaf noisy ones are deafened: everyone - [fs"]yoh (regressive assimilation due to deafness). But deaf noisy consonants before [v], [v"] do not become voiced: whistle - [sv"]ist, not [sv"]ist.

3. Assimilation by softness. Paired hard consonants, being in front of soft consonants, become similar to them and become soft: bridge - mo[s"t"]ik. Previously, before soft consonants, a hard consonant had to be replaced by a soft one, but in modern pronunciation there has been a tendency towards the absence of assimilative softening, although this law applies to some consonants.

4. Assimilation by hardness. Paired soft consonants, being in front of hard consonants, become similar to them and become hard: lag[r"] - lag[rn]y, grya[z"]i - grya[zn]y. However, such assimilation in the Russian language is inconsistent and occurs in isolated cases. In addition, it is associated with a certain structure of the word: it occurs only during the word formation of adjectives and (less often) nouns at the junction of a generating stem and a suffix: zve[r"] - zve[rsk"]ii, ko[n"] - ko[nsk" ]iy, styo[p"] - st[n]6th, knight[r"] - r'sha[rtstvo], etc.

5. Assimilation by place of formation (assimilation of whistlings before hissing ones). The consonants [s], [z] before sibilants become sibilants themselves and merge with them into one long sound (complete assimilation).

Dissimilation– dissociation of sounds in the stream of speech that are within one word. D. is characteristic of irregular speech. In literary language it is observed only in two words - soft and easy and in their derivatives.

In the Common Slavic language, D. tt - st, dt - st occurred, since according to the law of an open syllable in the Common Slavic language there should not be two plosive consonants next to each other, because in this case the first plosive consonant made the syllable closed. Fricatives did not close the previous syllable; they could be pronounced with the next syllable. Therefore, the combination of two plosives was eliminated in the common Slavic language of D. consonants. This led to the emergence of alternations of plosive consonants with fricatives: meta - revenge, delirium - to wander, weave - to weave. D. in colloquial pronunciations: bomb - bonba, tram - tranvay.

Simplification of consonant clusters. When three or more consonants are combined, in some cases one of the consonants drops out, which leads to a simplification of these groups of consonants. The following combinations are simplified: stn (local), zdn (holiday), stl (envious), stsk (tourist), stts (plaintiff), zdts (uzdtsy), nts (talantsa), ndts (Dutch), ntsk (giant), rdts or rdch (heart), lnts (sun). In words and forms formed from the bases of feelings -, health -, the consonant v is not pronounced. In almost all cases, simplification leads to the loss of the dental consonants d or t.

Among the historical simplifications of consonant groups, it is worth noting the loss of d and t before the consonant l in past tense verbs: I lead, but led; I weave, but I also weaved the loss of the suffix -l in past tense verbs in the masculine gender after stems with a consonant - I carried, but I carried, I could, but I could.

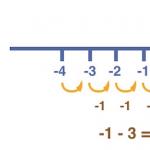

§1. The concept of positional alternation

Surprisingly, in Everyday life We regularly encounter different language processes. In this lesson we will talk about one of them. Let's consider the phenomenon of positional alternation of sounds (vowels and consonants). Let us note right away that we will talk about the phonetic process, and not about spelling.

In the flow of speech, the sounds we pronounce undergo various changes. Why is this happening?

The fact is that the sounds of the same morpheme (part of a word) fall into different positions: strong or weak.

Positional alternation- replacing one sound with another when its position in a word changes.

Strong position- this is a position in which the sound is clearly pronounced in a word, and in writing is conveyed by the corresponding sign (letter).

Weak positionThey consider one in which the sound is not heard clearly, is not pronounced at all, or is pronounced with changes. In this case, the spelling of the word is different from its pronunciation.

Let's look at the transcription of these words:

[mAroWith] and [heat]

Now let’s write these words in compliance with spelling rules:

mOroh, heat

Please note that the spelling of the first word is significantly different from its sound, and the second word is spelled the same way as it is heard. This means that in the word “frost” the first vowel and the last consonant sounds are in a weak position.

§2. Positional alternations of consonants

Let's find out which positions are strong and weak for vowels and consonants.

Doesn't change, is always therein a strong position consonant [th].

Strong position for hard and soft consonants is their position:

– at the end of the word: you[l] and tyu[ l"];

– before vowels:[ d]ub and [ d"] ate;

– before hard consonants: ba[n] ka and ba[n"]ka.

Weak Forhard and soft consonants is the position:

– before soft consonants: for example, in the word pi[s"m"] enlarged;

– before [sh"], [h"]: for example, in the word baraba[n"sh"]ik.

Voiceless and voiced consonants also have their ownweak and strong positions .

The sounds [l], [l'], [m], [m'], [n], [n'], [r], [r'], [th] do not have a voiceless pair, so there are no weak ones for them positions.

Strong positions for the remaining consonants in terms of deafness/voicing are the following:

– before vowels: volo[ s]s or[ h] uby;

– before consonants [l], [l'], [m], [m'], [n], [n'], [p], [p'], [th], [v] and [v"] : for example, in the words [z]loy and [ With] loy, [h]venet.

Weak positions :

– at the end of the word: steam[s];

– before voiceless and voiced consonants (except for [l], [l'], [m], [m'], [n], [n'], [r], [r'], [th], [v] and [in"]): povo[s] ka.

§3. Positional alternations of vowel sounds

Now let's look at positional alternations of vowel sounds.

Strong position for a vowel, the position is always stressed, and the weak position, accordingly, is unstressed:

v[a]r[O]ta

Often such alternation is typical only for vowelsO Ande .

Let's compare:

m[ó]kry - m[a]mole and wise - m[u]drec

There are also features in the pronunciation of sounds, which in writing are designated by the letters E, Yo, Yu, Ya.

Why do you need to know cases of positional (phonetic) alternation of sounds? You need to know this to develop spelling vigilance.

If you do not know these processes and do not recognize them in words, then you can make a mistake in using one or another spelling or when morphological analysis words.

One of the most striking evidence of this statement isrule :

In order not to make a mistake in spelling the consonant at the root of a word, you need to choose a related word or change the given word so that after the consonant you are checking there is a vowel.

For example, du[p] – du[b]y.

§4. Brief lesson summary

Now let us repeat once again what we have learned about such a phonetic process as positional alternation of sounds.

Alternation is the replacement of one sound with another.

Positional, i.e. depending on the position of the sound in the word.

Important to remember:

Positional alternation of sounds does not affect writing!

Sounds are characterized by strong and weak positions.

In a strong position, the sound is pronounced clearly and is represented in writing by the corresponding (own) letter.

For vowels, the position under stress is strong.

For soft and hard consonants, the strong position is the position at the end of the word, before a vowel or before a hard consonant.

For voiceless and voiced consonants, strong positions are also before the vowel and before the sonorant consonants [m], [m'], [n], [n'], [r], [r'] [l], [l'], [v], [v"] and [th].

In other cases, sounds change and alternate in the flow of speech - these are weak positions.