Frederick I of Hohenstaufen (Barbarossa) (1122-1190), Duke of Swabia from 1147, King of Germany from 1152, Holy Emperor Roman Empire from 1155

A participant in the Second Crusade (1147-1149) to Palestine for the liberation of the Holy Sepulcher, Duke of Swabia Frederick 1 of Hohenstaufen proved himself to be a valiant knight and a skilled commander. After returning from the campaign in 1152, he became king of Germany, and in 1155 - emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. In his character, Frederick was reminiscent of Charlemagne - he loved battles, was generous to the fallen, was distinguished by honesty and dreamed of reviving the former greatness of the Holy Roman Empire. On this path he did not take anything into account.

Little is known about his childhood and youth. He was the son of Duke Frederick II of Swabia (1090-1147) and nephew of the Holy Roman Emperor Conrad III (1093-1152), who also took part in the Second Crusade. During this campaign, Conrad got to know his nephew better, appreciated his courage, rationality, willingness to help and toughness in managing people. The young man had all the necessary qualities to be a commander. Before his death, the sick Conrad recommended Frederick as his successor.

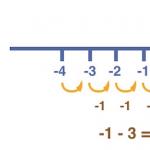

Frederick considered Charlemagne his idol and, once on the royal throne, the first thing he did was organize the army entrusted to him. He called to himself lonely knights, adventurers, everyone who would like to faithfully serve the sword and the cross, proving their rightness on the battlefield. Each warrior had to have his own horse, battle armor and weapons - a sword and a spear. Frederick created one of the first knightly cavalry in Europe, clad in steel armor, capable of breaking any enemy. By his decree, only a knight by birth had the right to participate in the knightly tournament. According to the ritual he introduced, a baldric, a knight's belt and golden spurs could be worn by a knight who was awarded them by the king. Later scholars called Frederick a classic of medieval military art.

In 1154, Frederick went to Italy to receive the crown from the hands of the Pope. In Italy, not everyone unconditionally accepted the news that a German duke would lead the Holy Roman Empire. They were preparing a real military reception for him. Due to the outbreak of unrest in Rome, the Pope was planning to leave the city. Frederick and his knights surrounded St. Peter's Basilica. He barely had time to accept the crown when street fighting began. They continued all night. The next day, Frederick, not wanting to worsen the situation, left Rome with the Pope with a feeling of deep dissatisfaction.

In 1158, he made a second Italian campaign, to which he attracted a significant number of knights - several thousand, an entire army. Venice, Florence, Genoa and Milan, which had become rich, did not want to obey either the Pope or the Holy Roman Emperor. They wanted to trade, get rich and not pay anyone anything. Milan was the first to surrender. The city fathers promised Frederick, who was nicknamed Redbeard - Barbarossa, not to mint his own coins, not to charge a toll. In the center of the city, Frederick ordered the construction of a castle in which the German garrison was to remain. He announced to his vassals that everything public - ports, rivers, bridges, cities - came under the control of the emperor, and only he had the right to mint coins. He also acted in other Italian cities. And after that he returned to Germany.

But more than once he had to go to Italy to pacify the rebels, either the Veronese, the Romans, or the Lombardians. He restored order with sword and spear, negotiated harshly with clergy and sought compliance from them. But as soon as he returned to his patrimony, they began to rebel again in Italy, drive out the German knights and live according to their own way of life. In total, Frederick made five trips to Italy. The Emperor had to soften his demands, give up many positions, and recognize the new Pope Alexander III, who, together with the Lombardians, opposed him. He agreed to a truce with Venice and other rebel cities.

While in Germany, Frederick began organizing the German lands, created the Duchy of Westphalia, the Duchy of Styria, and gave Bavaria to Count Wittelsbach. In 1183, a peace with Lombardy was signed in Mainz, according to which the Italian cities recognized him as their overlord, and Frederick recognized their ancient liberties.

If in central and southern Europe life gradually returned to a calm course, then in Palestine bloody clashes continued between Christians and Muslims, who trampled Christian values and desecrated the Holy Sepulcher. Frederick could not help but respond to the call of the Pope to take revenge on the infidels and return the shrines to the fold of the Christian Church. In 1189, Frederick set out on the Third Crusade to the Holy Land.

We went with him french king Philip II Augustus and the English King Richard I the Lionheart. But already during the campaign, clashes arose between them for supremacy. The kings could not divide the lands that had not yet been conquered. They quarreled and parted, each going his own way to Palestine.

The crusaders did not spare anyone on their way; they took food, horses, and weapons from the peasants. After them, there was groaning and crying in the empty villages. With great difficulty and huge losses they passed Hungary, Serbia, Bulgaria and in January 1190 approached Constantinople. But the Byzantine emperor, frightened by the invasion of the crusaders, entered into negotiations. He supplied them with food and provided ships for crossing the strait. The crusaders did not enter the city.

Frederick and his heavy knights had a particularly difficult time in hot countries, they could hardly stand the heat, they were tormented by thirst. In such conditions, they became easy prey for Muslim detachments, who flew in on their fast horses, killed and instantly disappeared. The army was melting.

In June 1190, Frederick and his detachment approached the fast-moving Selif River, which they had to ford. But during the crossing, the emperor’s horse stumbled, the rapid current knocked him out of the saddle and carried him away. The knights' attempts to save him were unsuccessful. This is official version death of Frederick Barbarossa. Another legend says that when Frederick was riding at the head of an army, he was attacked by Muslims and killed. The bodyguards, in order to hide their shame, told everyone that Frederick had drowned while crossing the river. This is hard to believe, since the emperor was an excellent swimmer.

- one of the most prominent representatives of the Hohenstaufen dynasty. Born around 1123, he was the son of Frederick One-Eye, Duke of Swabia, and as a young man participated in the Second Crusade, where he gained respect for his valor. Frederick I inherited the German and imperial throne after his uncle, Conrad III, in 1152. The glorious, eventful reign and outstanding personal talents of Frederick Barbarossa (this nickname means “Redbeard”) made him a hero of legends and tales for a long time. German legends attributed almost all the remarkable events of the Middle Ages to the personality of Frederick I. In the internal life of Germany, the reign of Frederick Barbarossa was marked by the strengthening of royal power, achieved through fierce struggle.

Barbarossa had a lively mind, was a pleasant conversationalist, an excellent knight, an intelligent and talented sovereign. But in moments of anger, he was extremely harsh and often resorted to bloody cruelty to achieve his goal. His lust for power was immeasurable. As soon as he assumed power, Frederick I began to prepare for a campaign in Italy to be crowned with the imperial crown in Rome and strengthen the power of the German monarch over the Apennines. In his dreams, he dreamed of restoring the power of the ancient Roman Empire to all its greatness. This task was not easy. On the way to her goal, Barbarossa had to face the papacy and the Lombard cities, which by that time had strengthened, become rich and became almost independent of the imperial power. But Frederick I, already in the first period of his reign, became convinced that even European sovereigns independent of him (the kings of England and France) were inclined, if not in deed, then in word, to recognize imperial supremacy. This supported Barbarossa’s proud dreams.

Frederick Barbarossa with his sons Henry and Frederick

Pope Adrian IV was then in great need of Frederick's help, because he was fighting the Roman nobility. In 1143, she formed the Senate, seized control of the city into her own hands and forced the pope to flee Rome to Viterbo. The Senate suggested that Barbarossa receive the crown from the hands of the Roman people, but the king replied that he did not want the temporary favors of the restless crowd, and, if necessary, he would take the inheritance of his fathers by force of arms. Having crossed the Alps, Frederick I at the end of 1154 acted as the supreme arbiter in the civil strife of the Lombard communities and ruined those of them that he recognized as the culprits of the troubles. In the summer of 1155, Barbarossa's army approached Rome. Having entered the city, the Germans occupied all approaches to St. Peter's Cathedral on the night of June 17-18, and Pope Adrian solemnly crowned Frederick with the imperial crown here. But the Romans, dissatisfied with this, already in the evening of the same day moved to attack the quarters of St. Peter. There was a bloody battle all evening. Although Barbarossa's soldiers repulsed the attack of the townspeople, the next morning, June 19, the emperor and pope had to leave the Eternal City. In September, Frederick I returned to Germany.

All this, however, only encouraged the king to continue the fight for Italy, which in the era of recent German unrest had become almost independent of the emperors. In order to establish German dominance in Italy, it was necessary to conquer it again. In 1158 Frederick Barbarossa set out on his second Italian campaign. Shortly before this, he quarreled with his former ally, the papacy, which saw in the events of 1155 a sign of German weakness. Pope Adrian IV in 1157 entered into sharp disputes with Frederick I over the issue of the origin of imperial power. Like Gregory VII, Hadrian argued that emperors, the main secular rulers of Christendom, receive their crown and power from its supreme pontiffs - the popes. Adrian and his successor Alexander III claimed to be overlords of the emperors and to reduce Barbarossa to the rank of their fief.

The main goal Frederick I now had to conquer Milan, the strongest city in Lombardy, which had long maintained itself extremely independently. Barbarossa attracted all the German princes to the campaign and assembled a huge army. Powerful Milan responded by rallying around itself other strong Lombard communities - Brescia, Piacenza, Parma, Modena. In August, Frederick I besieged Milan, and on September 1 it capitulated. The Milanese had to pay a huge tribute, hand over hostages, give up the right to mint coins and collect road tolls. More importantly, they recognized Barbarossa’s right to appoint elected heads of city government. The submission of Milan to the emperor was arranged very solemnly: the entire population of the city came to Frederick’s camp and begged for forgiveness and mercy. Frederick built a castle in Milan and stationed his garrison there.

This victory of his made a great impression on the Lombards. On November 11, 1158, Frederick convened a Diet on the Roncal Field, where he announced to the Italians the principles on which he intended to govern their country. These principles, according to the old autocratic principles of Roman law, were formulated by the Bolognese jurists who served Barbarossa. Roads, navigable rivers, and ports were to come under the control of imperial officials, and the collection of taxes and coinage became the exclusive prerogative of imperial power. Frederick Barbarossa strictly demanded military service from local princes and cities and threatened to take away the fiefs from all those who disobeyed. Civil strife was strictly prohibited. Representatives of the Lombard cities inevitably had to agree at the Diet to close subordination to the emperor.

The Diet of Roncala was supposed to make Frederick Barbarossa complete master of Lombardy. However, soon after its closure, the riots resumed. The Genoese declared that they would give Frederick only what he could claim ownership of. In January 1159, the Milanese rebelled again, supported by the inhabitants of Crema and Brescia. Meanwhile, Frederick, relying on his first success, had already sent most of his troops beyond the Alps. The remaining forces were not enough for a new siege of Milan. In July 1159, Barbarossa approached Crema, stubbornly besieged it for six months and, having captured this city in January 1160, destroyed it to the ground.

Meanwhile, in Rome, after the death of Adrian IV, Frederick's opponents elected Alexander III as pope, and the emperor's supporters elected Victor IV. Barbarossa convened a council of loyal clergy in Pavia, which declared Alexander deposed. Alexander, in turn, excommunicated Barbarossa from the church, and freed his subjects from the oath. Having gathered his troops again, Frederick besieged Milan for the second time in May 1161. The siege lasted almost a year, until in March 1162 the city surrendered without any conditions. Frederick ordered all residents to leave with whatever property they could carry and settle in four unfortified cities. Milan was ruined to the ground. After this, Piacenza, Brescia and other cities surrendered to Barbarossa. Frederick I ordered the residents to dismantle the city walls, pay an indemnity and accept imperial governors - podestes - into their cities.

In 1163, Frederick Barbarossa began preparing for a campaign against Rome. However, in Lombardy, Venice, Verona, Vicenza and Padua united in an anti-German league. In April, the imperial antipope Victor IV died. Paschal III, who was elected in his place, had much fewer supporters than Alexander III. Barbarossa's forces again proved insufficient. In the fall of 1164 he went to Germany to gather a new army, but was detained there by business for a year and a half. Only in the spring of 1165 Frederick I crossed the Alps with a large army and moved towards Rome. On June 24, 1165, the Germans besieged the Castle of Sant'Angelo and occupied the entire left bank of the Tiber. Alexander III took refuge in the castle of Frangipani next to the Colosseum. Frederick suggested that both popes resign and hold new elections. Alexander refused, and the fickle Romans, suffering under the German invasion, turned against the pope. Alexander had to flee Rome. Frederick Barbarossa solemnly entered the city. On June 30, the enthronement of Paschal, who fell under the strong influence of Frederick, took place in the Church of St. Peter. The Senate and the prefect of the city began to submit personally to the emperor. Barbarossa was again close to his cherished goal, but unforeseen circumstances confused his plans. In August, a severe plague epidemic began in the German army. There were so many dead that Frederick hastily took his soldiers to northern Italy. Here he learned that the previously formed league of his enemies had been joined by Cremona, Bergamo, Brescia, Mantua and the Milanese, who began hastily rebuilding their city. Barbarossa's representatives (podestas) were expelled from everywhere. Frederick no longer had a strong army, and he could not resist the rebellion. On December 1, 1167, sixteen rebel cities united into the Lombard League, vowed not to conclude a separate peace and to wage war until they regained all their former freedoms. At the beginning of 1168 Frederick went to Germany. On the way, he was almost captured and had to escape, dressed in someone else's dress. His power over Italy almost completely collapsed.

Difficulties kept Barbarossa in Germany for seven years. In 1173 he once again marched into Italy against the Lombard League. In order not to depend on unreliable princes, Frederick recruited many Brabant mercenaries. In September 1174, Barbarossa crossed the Alps for the fifth time, and in October he besieged Alessandria, a new Lombard city that his enemies named after Pope Alexander III. The Lombards stubbornly defended themselves. In April of the following year, having failed to achieve success, Frederick Barbarossa began negotiations and dismissed the soldiers, whom he could not pay. But consultations that lasted almost a whole year led to nothing. Preparing to resume the war, Barbarossa invited the powerful Duke of Bavaria and Saxony, Henry the Lion of the Welf family, to Chiavenna and asked him for help, even going to the extent of humiliation in his pleas. But Henry the Lion refused to support the emperor in the Italian war. Frederick I, with great difficulty, recruited several thousand soldiers and marched on Milan. On May 29, 1176, he, not having sufficient forces, met with enemies at Legnano. The German knights, as usual, rushed into a powerful attack, broke through the line of Lombard cavalry, and it fled in disarray. But when the Germans attacked the infantry lined up in a square, their attack floundered. Meanwhile, the Lombard cavalry, having met an army from Brescia coming to their aid, returned to the battlefield and suddenly attacked the Germans from the flank. Frederick bravely rushed into the thick of the battle, but was knocked out of the saddle. A false rumor about his death spread throughout the troops. Throwing down their weapons, the knights fled from the battlefield to Pavia. Barbarossa suffered a terrible defeat, barely escaping capture and death.

Through the skillful diplomat Christian, Archbishop of Mainz, Frederick I began negotiations with the Lombard League and Pope Alexander. Thanks to the discord between Barbarossa's Italian enemies, the outcome of the negotiations was very favorable to him. Frederick agreed to recognize Alexander III as the only legitimate pope, returned him the prefecture in Rome and recognized Tuscany as his fief. In exchange, the pope lifted his excommunication. At the peace congress in Venice in 1177, Frederick I made peace with Alexander III, but with the Lombards - so far only a six-year truce. At a personal meeting with the pope, Barbarossa kissed his leg and showed all the outward signs of submission.

Having reconciled with the Italians, Frederick I returned to Germany, where he started intrigues against Henry the Lion. The Bishop of Halberstadt complained that Henry had taken some areas from him. In January 1179 the Duke was summoned to the royal tribunal, but refused to come. Taking advantage of this, Frederick Barbarossa accused him of rebellion. At a congress in Würzburg in January 1180, the powerful Henry the Lion was sentenced to be deprived of all his fiefs. East Saxony was given to Count Bernhard of Anhalt. From West Saxony, Frederick I formed a new Duchy of Westphalia, which he retained for himself. Bavaria was given to Count Otto von Wittelsbach, whose descendants then owned this area until the beginning of the 20th century. The Styrian Mark was taken away from Bavaria and turned into a special duchy. In 1180, the emperor led troops to Saxony, took Brunswick and besieged Lubeck. In November, Heinrich Leo came to a congress in Erfurt and threw himself at Frederick’s feet. Barbarossa forgave him, returned Brunswick, but retained all other Welf possessions and ordered Henry to go into exile for three years. So, having lost the fight with the Italians, Frederick I strengthened royal power in Germany.

In 1183, peace was finally signed in Constance between Barbarossa and the Lombard League. The cities recognized the emperor as their overlord, and Frederick confirmed their ancient liberties, including the right to build fortifications and create leagues. The emperor formally retained the right to invest city consuls. Barbarossa did not give up plans to revive imperial greatness. Having stopped the fight in Northern Italy, he began to plant his influence in the south of it and agreed on the marriage of his son and heir Henry to the heiress of the Sicilian kingdom, the aunt of his sovereign, William. Constance. In 1184, Frederick I organized a luxurious congress near Mainz in honor of his son, one of the most magnificent holidays in all medieval history. This triumph, which amazed the crowds of those gathered, was sung by chroniclers and poets. In 1186, the marriage of young Henry and Constance of Sicily took place. The Papacy was very unhappy with this increase in imperial influence in southern Italy. A new struggle was brewing between Frederick Barbarossa and Rome, but the situation was dramatically changed by the news that shocked Europe about the capture of Jerusalem by the Egyptian Sultan Saladin.

Frederick Barbarossa - Crusader

Frederick immediately announced that he would go on a campaign to recapture Jerusalem from the Muslims (Third Crusade). He gathered the flower of German chivalry under his banners. In May 1189, Barbarossa set out on a crusade to the East with an army of one hundred thousand. In the summer, the crusaders entered the Byzantine possessions, where they soon entered into quarrels with byzantine emperor Isaac Angel, who was very concerned about the entry of the Germans into the Balkans, which rebelled against the Greeks. Frederick Barbarossa entered into relations with the Serbs and Bulgarians hostile to Byzantium, occupied all of Macedonia, took Adrianople at the end of November and even thought of attacking Constantinople. However, they still managed to come to an agreement with the Greeks, and in the spring of 1190, the army of Frederick I crossed to Asia Minor on Greek ships.

The trek through Asia Minor was also very difficult. Barbarossa skillfully led his army through hostile Muslim areas. He won several skirmishes with the Seljuks and took Konya on May 18. But when on June 10 the German army approached the Selif River, when crossing it, Frederick I was unable to control his horse, which got scared and stumbled. Barbarossa fell into the water and was carried away by the current. When the emperor was pulled out of the water, he was already dead. The German campaign was subsequently frustrated, but remained, however, one of the favorite subjects of folk legends about Frederick I.

According to another German legend, Frederick Barbarossa did not die, but slept in a cave under Mount Kyffhäuser, so that one day he would return. The long beard of the sleeping emperor continues to grow.

Monument to Friedrich Barbarossa at Mount Kyffhäuser. Barbarossa's grown beard encircles the throne

Frederick I Barbarossa

FRIEDRICH I HOHENSTAUFEN (Barbarossa) (c. 1125-1190) - German king from 1152, emperor of the “Holy Roman Empire” from 1155, who considered himself the heir of the Roman Caesars and the legitimate sovereign of not only the West, but and East.

Constantly at odds with the Byzantine Empire and Pope Alexander III in the struggle for the conquest of Italy. He died during the Third Crusade, when his troops passed through the territory of Byzantium.

Orlov A.S., Georgieva N.G., Georgiev V.A. Historical Dictionary. 2nd ed. M., 2012, p. 541.

Frederick I Barbarossa (1123-1190) - German king and emperor "Holy Roman Empire" from the Hohenstaufen family, who ruled from 1152 to 1190.

Wives:

1) from 1147 Adelheide, daughter of Dupold II, Margrave von Voburg;

Frederick was the son of Frederick One-Eye, Duke of Swabia, and the nephew of Emperor Conrad III. In 1147, after the death of his father, he became Duke of Swabia. He soon took part in the Second Crusade, during which he gained universal respect thanks to his courage and valor. Returning to Germany, the sick emperor recommended that the princes elect Frederick as their successor. He died in February 1152, and already on March 4, Frederick took the empty throne. The new king was a young and physically very strong man, possessed of a lively mind, a pleasant and even charming interlocutor, an excellent knight, greedy for difficult undertakings and glory, an honest and generous sovereign, a kind and firm Christian. But these advantages did not cover the shortcomings that were common, however, in the monarchs of that time. Thus, in moments of anger, Frederick was extremely stern, did not tolerate opposition, and was sometimes ready for bloody cruelty to achieve his goal. His lust for power was immeasurable, but he never dreamed of extraordinary enterprises and stormy successes. Everything he took on was realistic and thought out. Therefore, luck often accompanied him even in the most difficult enterprises. And although the main dream of his life - to revive the former power of the empire of Charlemagne - remained unfulfilled, he did a lot along this path.

As soon as he assumed power, Frederick began to prepare for a campaign in Italy. German affairs delayed him for two years. Finally, in October 1154, the German army crossed the Alps. At this time, Pope Adrian IV waged a stubborn struggle with the Roman nobility, which in 1143 formed the Senate and seized control of the city into its own hands. Due to the outbreak of unrest, the pope had to leave his residence and moved to Viterbo. The Senate suggested that Frederick receive the crown from the hands of the Romans themselves, but the king arrogantly replied that he had arrived in Italy not to beg for the temporary favor of a restless people, but as a prince determined to obtain, if necessary, by force of arms, the inheritance of his fathers. On the night of June 17-18, the Germans occupied all approaches to St. Peter's Cathedral. Hadrian solemnly crowned Frederick with the imperial crown here. But in the evening the Romans moved from the Capitol to attack the quarters of St. Peter. There was a bloody battle all evening, and the attack of the townspeople was repulsed. The next morning, June 19, the emperor and pope left the eternal city, which they never truly entered. Convinced that nothing more could be done, Frederick returned to Germany in September. From that time on, his thoughts were constantly directed towards Italy. He knew before and during the coronation he was finally convinced that this country over the past decades had become virtually independent of the empire and in order to establish German dominance in it, it was necessary to conquer it again. This time Frederick carefully prepared for the invasion. In 1158 he set out on his second Italian campaign. His main goal was the conquest of Milan, since since the time of Conrad II this city had become accustomed to demonstrating its independence and remained the main stronghold of all opponents of the empire in Lombardy. To be sure, Frederick tried to attract all the German princes to the campaign and assembled a huge army. The large superiority in forces allowed his plans to get off to a successful start. In August, Milan was besieged and capitulated on September 1. The Milanese had to pay a huge tribute, hand over hostages, give up the right to mint coins and collect road tolls. In the center of the city, Frederick erected a castle and placed his garrison. This bloodless and easy victory made a great impression on the Lombards. Having convened a congress in Roncale, Frederick brought to the attention of the Italians the principles on the basis of which he now wanted to organize the management of his Trans-Alpine possessions. Public roads, navigable rivers and tributaries, ports and harbors were to come under the control of imperial officials, and the collection of taxes and coinage became the exclusive prerogative of the imperial power. At the same time, the emperor strictly demanded military service from his vassals and threatened to take away the fiefs from all those who disobeyed. Internecine wars were strictly prohibited.

The new edicts most of all infringed on the rights and freedoms of the Lombard cities, which by this time had become almost completely independent of their feudal lords. From their side, Frederick encountered the strongest opposition. The Genoese declared that they would give Frederick only what he could claim ownership of. In January 1159, the Milanese rebelled again, dissatisfied with the fact that the emperor tried to establish his proteges in power here. They were supported by the residents of Crem and Brescia. Meanwhile, Frederick, relying on his first success, had already sent most of the allied forces. The remaining forces for a new siege of Milan were clearly not enough. In July 1159, the emperor approached Kremy and stubbornly besieged it for six months. Having finally captured this small fortress in January 1160, Frederick ordered it to be destroyed to the ground. Added to other difficulties were feuds with the papal throne. After the death of Adrian IV, Frederick's opponents elected Alexander III as pope, and his supporters elected Victor IV. The emperor convened a church council in Pavia, which declared Alexander deposed. Alexander was not embarrassed by this and, in turn, excommunicated Barbarossa from the church, and freed his subjects from the oath. Frederick realized that he had to march on Rome. But first he wanted to establish himself in Italy. Having summoned vassals from Germany and Italy, Frederick besieged Milan for the second time in May 1161. A year later, in March 1162, the city surrendered without any conditions to the mercy of the winner. Frederick ordered all residents to leave the city with whatever property they could carry and settle in four unfortified cities. The city itself was completely destroyed. After this main enemy was crushed, Piacenza, Brescia and other cities surrendered. The emperor ordered the residents to dismantle the city walls, pay an indemnity and accept a governor - the podest.

Having traveled briefly to Germany, Frederick returned to Lombardy in the fall of 1163 and began preparing for a campaign against Rome. However, new difficulties stopped him. Venice, Verona, Vicenza and Padua united in an anti-German league. Victor IV died in April. Paschal III, who was elected in his place, had much fewer supporters than Alexander III. The emperor tried to attack Verona, but he had too few forces to wage a serious war. In the fall of 1164, he went to Germany, where he hoped to gather a new army. Business again delayed him for a year and a half. Only in the spring of 1165 did Frederick cross the Alps with a large army and march directly towards Rome. On June 24, the Germans besieged the Castle of Sant'Angelo and occupied the entire left bank of the Tiber. Alexander III took refuge in the castle of Frangipani next to the Colosseum. Frederick suggested that both popes resign from office and hold new elections to avoid bloodshed. Alexander refused, and this greatly damaged him in the eyes of the townspeople. The notoriously fickle Romans turned against the pope, and he had to flee to Beneventum. The Emperor solemnly entered the city, and on June 30, Paschal was enthroned in the Church of St. Peter. However, Frederick did not leave to his supporter even a shadow of the power that the popes had enjoyed before him. The Senate and the prefect of the city began to submit personally to the emperor, who thus took control of Rome. into your own hands. It seemed that Frederick had reached the limits of his desires. But then unforeseen circumstances confused all his plans: in August, a severe plague epidemic began in the German army. There were so many dead that Frederick hastily took his soldiers to northern Italy. Here he was alarmed to discover that the position of his enemies had strengthened; the previously formed league was joined by Cremona, Bergamo, Brescia, Mantua, as well as the inhabitants of Milan, who hastily rebuilt their city. Unfortunately, Frederick no longer had an army, and he had to watch powerlessly from Pavia as the rebellion flared up. On December 1, 1167, sixteen rebel cities united into the Lombard League. They vowed not to conclude a separate peace and to wage war until they returned all the benefits and freedoms that they had under the previous emperors. At the beginning of 1168, Frederick decided to make his way to Germany. On the way to Susa, he was almost captured and had to escape, dressed in someone else's dress.

This time the emperor spent seven years in Germany, busy solving pressing matters and strengthening his power. In 1173, he announced his decision to return to Italy and lead an army on a campaign against the Lombard League. In order not to depend on the princes, who more than once left him without warriors at the very critical moment, he recruited many Brabant mercenaries. In September 1174, Frederick crossed the Alps for the fifth time, and in October he besieged Alersandria. The Lombards stubbornly defended themselves. In April of the following year, having failed to achieve success, Frederick began negotiations and dismissed the soldiers, whom he could not pay. But consultations that lasted almost a whole year did not lead to anything, since the positions of the parties were too different. It was necessary to prepare for war again. The emperor invited his cousin, the powerful Duke of Bavaria and Saxony Heinrich Leo from the Welf family, to Chiavenna and asked him for help. Henry the Lion refused, which greatly offended Frederick. With great difficulty, he recruited several thousand soldiers in Italy and marched with them to Milan. On May 20, 1176, the opponents met near Legnano. The German knights, as was their custom, rushed into a powerful attack, broke through the line of Lombard cavalry, and it fled in disarray. But when the Germans attacked the infantry lined up in a square, their attack floundered. Meanwhile, the Lombard cavalry, having met an army from Brescia rushing to their aid, returned to the battlefield and suddenly attacked the Germans from the flank. Friedrich rushed into the very rubbish with ardor and courage, but was knocked out of the saddle. Immediately the rumor of his imaginary death spread throughout the troops. Throwing down their weapons, the knights fled from the battlefield and took refuge in Pavia.

After this defeat, Frederick had to soften his position and make big concessions: he agreed to recognize Alexander III as the only legitimate pope, returned the prefecture in Rome to him and agreed to recognize the Margraviate of Tuscany as his fief. In exchange for this, the pope lifted his excommunication. Having made peace with the pope, Frederick returned to Lombard business. But it was not possible to come to an agreement with the rebel cities. In July 1177, in Venice, Frederick signed a truce with them for six years and in the summer of 1178 he went to Burgundy, where he was crowned King of Burgundy in Arles. In Germany, he took the first opportunity to begin to oppress Henry the Lion. At the congress in Speyer, Bishop Ulrich of Halberstadt complained that the Duke had seized fiefs belonging to his diocese. In January 1179, Henry was summoned to the royal tribunal to consider this issue, but refused to come. In June he did not come to the congress in Magdeburg. This made it possible to start another process against him: Frederick accused him of rebellion. At a congress in Würzburg in January 1180, the powerful Welf was sentenced to be deprived of all his fiefs. East Saxony was given to Count Bernhard of Anhalt. From the West Saxon lands, Frederick formed a new Duchy of Westphalia, which he retained for himself. Bavaria was given to Count Otto von Wittelsbach. The Styrian mark was also taken away from her and turned into a duchy. In 1180, the emperor led troops to Saxony, took Brunswick and besieged Lubeck. In the summer of 1181, Henry the Lion realized that his cause was lost. In November he came to a congress in Erfurt and threw himself at the feet of Frederick. Barbarossa forgave him, returned Brunswick, but retained all other Welf possessions. In addition, the Duke had to go into exile for three years. The conflict with the Lombards was also gradually settled. In 1183, peace was signed in Constance with the Lombard League. The cities recognized the emperor as their overlord, and Frederick agreed to preserve their ancient liberties, including such important ones as the right to build fortifications and organize leagues. The emperor retained the right to invest city consuls; his court was recognized as the highest authority. In 1184, Frederick recognized the royal title of William of Sicily, who agreed to marry his aunt Constance to Frederick's son, Henry. (Back then, no one could have imagined that this marriage would bring Sicily to the Hohenstaufens in the future.) Having pacified Italy and established calm throughout the empire, Barbarossa began to prepare for a crusade. In March 1188, at a congress in Mainz, he solemnly accepted the cross.

Remembering the failure of the previous campaign, Frederick prepared for the new enterprise with great care and really managed to gather the flower of German chivalry under his banner. During his absence, he transferred control of the state to his son Henry and in the spring of 1189 he set out from Ratisbonne on the Danube. Having safely passed Hungary, Serbia and Bulgaria, the crusaders entered Byzantium in the summer. As before, misunderstandings soon arose between the Germans and Greeks. The envoys of Emperor Isaac Angel demanded hostages from Barbarossa and an undertaking that he would cede part of future conquests. Frederick sent envoys to the emperor, whom the Angel ordered to be thrown into prison. At the news of this, Frederick broke off the negotiations and led his army to Constantinople, abandoning everything in his path to devastation. At the end of November, the crusaders took Adrianople. Only after this did Isaac enter into negotiations with him, and in January 1190 an agreement was concluded. Frederick promised not to pass through Constantinople, for which the Byzantine emperor provided the Germans with food and promised to transport them across the strait. The trek through Asia Minor was also very difficult. On May 18, the crusaders took Konya by storm.

On June 10, the army, accompanied by Armenian guides, approached the Selif River. When crossing it, the emperor was unable to control his horse; he got scared and stumbled. Friedrich fell into the water, the current caught him and carried him away. When the emperor was pulled out of the water, he was already dead.

All the monarchs of the world. Western Europe. Konstantin Ryzhov. Moscow, 1999

Image of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa

on the western portal of the cathedral in Freising. XII century. Germany.

Drowned in the Salef River

FRIEDRICH I (Friederich I Barbarossa) (c. 1122–1190), often referred to simply as Barbarossa (Italian: “Red Beard”), German king and Holy Roman Emperor, the first prominent representative of the Hohenstaufen dynasty. Frederick, the son of Duke Frederick II of Swabia and Judith (daughter of Duke Henry IX of Bavaria, a representative of the Welf family at war with the Hohenstaufen), was probably born in Waiblingen. On his father's side he was the nephew of the German king Conrad III, and on his mother's side he was the nephew of Henry X the Proud, Duke of Bavaria and Saxony. After the death of his father in 1147, Frederick became Duke of Swabia (as Frederick III), and when Conrad died in 1152, he was elected king of the Germans. The nation was then torn apart by internal contradictions, and one of the main conflicts occurred precisely between the Welf and Waiblingen (Hohenstaufen) dynasties. Being connected by family ties with both, Frederick was able to end the difficult conflict for a long time, returning the duchies of Saxony and Bavaria to his cousin Henry the Lion (son of Henry X the Proud, i.e. Welf). At the same time, Frederick was able to give some compensation to other German princes who also laid claim to these possessions, which reduced their discontent. In 1155, Frederick was crowned emperor in Rome by Pope Adrian IV, whom he helped suppress the unrest that had continued in Rome since 1143, which led to the establishment of a republic in the city. One of the leaders here was a religious ascetic, Abelard’s student Arnold of Brescia, who, under pressure from the pope and under the threat of the approaching Frederick, fled to Tuscany, but Frederick’s knights captured him and handed him over to the pope, who put Arnold to death at the stake. The main goal of Frederick's Italian campaigns (there were five in total: 1154–1155, 1158–1162, 1163–1164, 1166–1168, 1174–1178) was to restore German legal and administrative control over the cities of northern Italy. To put his power on a legal basis, in 1158 Frederick called to the Reichstag, held in Roncali (near Piacenza), Bolognese jurists who specialized in the study of the recently revived Roman law. They gave the imperial regime the name Sacrum imperium (Latin for “Holy Empire”).

The reason for protracted conflict Frederick's relationship with the papacy (1160–1177) was facilitated by the fact that the emperor continued to assert his claims to power over Italy. He refused to recognize Alexander III as pope, who had become a champion of the movement against imperial control of Italy. But Frederick's attempts to establish German control over the papacy failed both because of spiritual resistance to such control by other powers of Western Europe, and because of the armed opposition of the cities of northern Italy, united in the Lombard League. In 1177, Frederick was forced to recognize Alexander III and, through the Peace of Constance (1183), reached a compromise with the cities of Lombardy, which retained political autonomy and at the same time respected their financial interests; The emperor's political power over Tuscany was preserved.

In 1180, Frederick, together with German sovereigns hostile to Henry the Lion, tried to overthrow this powerful duke: Henry was deprived of most of his possessions and sentenced to three years of exile from Germany. But the emperor was unable to take advantage of this to strengthen his position as the sovereign ruler of northern Germany. In 1186, Frederick achieved what appears to be the greatest achievement of his diplomacy: the marriage of his son Henry VI with Constance, heir to the throne of the Kingdom of Sicily. Henry VI also became his father's heir to the imperial throne. In May 1189, Frederick led the 3rd Crusade, but on June 10, 1190, on the way to the Holy Land, he drowned while crossing the Salef River (modern Göksu) in Asia Minor.

Materials from the encyclopedia "The World Around Us" were used

Frederick I Barbarossa

The date of birth of Frederick Barbarossa is not even approximately known. He saw his life and his greatness only on the battlefield, and was a typical representative of the German crusader knighthood. Friedrich received his nickname for the color of his beard. He was distinguished by exceptional belligerence and a constant desire for territorial conquests.

Frederick Barbarossa became the German king in 1125; only after this date did historians have the opportunity to trace his life path.

Frederick Barbarossa, as well as other warlike monarchs of the European Middle Ages, demanded from German knights perfect mastery of all seven knightly arts. These included: horse riding, swimming, archery, fist fighting, falconry, playing chess and writing poetry.

Frederick Barbarossa religiously adhered to feudal law for the title of knight. According to his decree, only those who were knights by birth had the right to a knightly duel with all its attributes. Only a knight could wear a baldric, a knight's belt and golden spurs. These items were the favorite rewards of the German knights, with which the king encouraged them.

In 1152, Frederick I Barbarossa became Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, which included numerous German states and modern Austria, which played a leading role in the empire.

Having become emperor, Frederick Barbarossa began to pursue an aggressive, aggressive policy that met the interests of the German feudal lords. He sought to bring the rich Lombard city-states of Northern Italy under his rule.

Frederick Barbarossa committed five conquests to Northern Italy: in 1154-1155, 1158-1162, 1163-1164, 1166-1168 and 1174-1178. All these campaigns became a unique, living history of the life of the conquering emperor, who dreamed and tried to annex a large part of neighboring Italy to his huge imperial possessions. Barbarossa saw the ultimate goal of these campaigns as crowning himself with the imperial crown in the Eternal City - Papal Rome.

In world history, the year 1189 marked the beginning of the Third Crusade to the Holy Land. It was headed by the three largest European monarchs - the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, the French king Philip II Augustus and the English king Richard the Lionheart. They all had their own troops and were constantly at odds with each other, laying claim to the main command and the glory of the winner.

Initially, the number of participants in the Third Crusade reached almost 100 thousand people. But on the way to Palestine, the army suffered heavy losses in skirmishes with the Muslim troops of the Sultan Saladin (Salah ad-Din). Frederick I Barbarossa led his army through the territory Byzantine Empire by land (French and English crusaders reached Palestine by sea) - the road was explored back in the First and Second Crusades. In Asia Minor he had to repel attacks from light Muslim cavalry every now and then.

However, the German commander did not have the chance to reach the Holy Land. While crossing the Salef River, Frederick Barbarossa drowned. After his death, the German army began to disintegrate even before arriving at its destination - it simply did not have a worthy leader.

Under Frederick I Barbarossa, the medieval Holy Roman Empire reached its greatest prosperity and military power. However, inside it remained virtually fragmented and therefore had no prospects for long-term existence.

REIGN OF FREDERICK I BARBAROSSA. He was the most outstanding ruler of the Hohenstaufen dynasty. In an intermittent war with Henry the Lion, Frederick I eventually defeated and deposed the Duke of the Welfs (1182). In between the Italian campaigns, he conducted several successful campaigns in Poland, Bohemia and Hungary (1156 -1173).

1154-1186 SIX ITALIAN CAMPAIGNS OF FRIEDRICH. Frederick I waged an ongoing struggle against the papacy with varying degrees of success. Although he captured Rome on his fourth campaign (1166-1168), he was soon forced to withdraw troops from Italy, as an epidemic began to rage in the army. The fifth campaign (1174 -1177) ended in a catastrophic defeat at the Battle of Legnano (May 29, 1176), when Frederick, at the head of a purely cavalry army, recklessly took on the superior forces of the Lombard League, supported by Venice and the pope. The Italian spearmen held their position and repelled the attack of Frederick's cavalry; and the Lombard cavalry outflanked and encircled the German army. (It is sometimes erroneously claimed that at Legnano, for the first time in military history, infantry prevailed over cavalry; but the Lombards achieved success precisely because of the coordination of infantry and cavalry.)

1189-1190 THIRD CRUSADE. Frederick I Barbarossa drowned in Cilicia (1190). Important events in the history of Germany and in the destinies of the Holy Roman Empire are associated with the name of Frederick I Barbarossa. There are significant differences in the assessment of the policies of this emperor in German historiography. Some attribute to him the desire to strengthen royal power in Germany, expand and consolidate the domain, which was supposed to unite the state. They explain Barbarossa's energetic Italian policy with these internal German tasks. Italy, thus, had to cover the costs of strengthening the German state (K. Gampe, I. Haller, D. Schaeffer, etc.). Others, on the contrary, believe that Frederick I no longer thought about uniting Germany, but only sought to maintain the existing balance political forces, relying on separate groups of princes. According to these historians, Barbarossa’s Italian policy did not at all contribute to the strengthening of royal power in Germany, but only required enormous costs from the internal funds of the German state. Italian policy did not strengthen the position of the emperor, but increased the emperor’s dependence on the princes (G. Belov, F. Kern, M. Lintzel). There is, perhaps, some truth in this.

The main levers of the royal policy of Frederick Barbarossa, like other representatives of the Hohenstaufen dynasty who preceded him, were: the creation of a compact domain, political alliances with individual groups of princes, strengthening of power over the episcopate, expansion of the imperial ministeriality and strengthening of fief dependence of small vassals on royal power.

Frederick I, trying to strengthen the national military organization, demanded mandatory military service the king of all holders of military fiefs. Along with the knights of free origin, the main contingent of warriors were the royal ministerials. It was during the time of the Staufens that the imperial ministerial body took shape, which had special status and the most privileged position among the service class. The emperors also used contingents of ministerial soldiers belonging to bishops and abbots in their military campaigns in Italy. An important role was played by the economic ministry, which filled the judicial and administrative apparatus on the royal estates. The ministerials also constituted a kind of internal garrison troops of the royal fortresses, guarding the domain and suppressing protests against the king.

In the internal German policy of Frederick I and his successors, one desire has always prevailed - to maintain good relations with the princes. The time when German kings tried to subjugate all the feudal nobility in the country to their rule is irrevocably over. Now it was possible to reign only by seeking an agreement with the princes, either with all of them at once, or with individual rival factions. It was along this path that Frederick Barbarossa followed. His entire policy in Germany was based on balancing between warring factions of princes, which provided the opportunity to implement far-reaching imperial plans in Italy.

Immediately after his enthronement, Frederick I tried to normalize relations with the most influential princes with whom his predecessor was at enmity. He returned Saxony and Bavaria to his cousin Henry the Lion (son of Henry the Proud). At the same time, Barbarossa did not offend Heinrich Yazomirgot (from the Babenberg dynasty), transferring to him Austria into hereditary possession (with the right of inheritance even through the female line), which was separated from Bavaria and turned into an independent duchy (1156). This fact is of interest from different points of view. First of all, it testifies to the far-advanced process of formation of territorial princely power. The newly created duchy had the legal status of an autonomous principality - full jurisdiction and military independence. The duke was obliged to carry out only very limited military duties: to appear at the invitation of the king to the curia, if it was convened within Bavaria, and to send a contingent of soldiers for military operations in neighboring regions.

The creation of new duchies pursued well-known political goals, quite consistent with the policy of maneuvering between princely groups: the old duchies were disaggregated and lost their former power; the rulers of the new duchies, having received their powers from the hands of the king, became, at least for the first time, his allies. One way or another, this strengthened the position of royal power, although reverse side was the strengthening of territorial fragmentation in the country. Barbarossa skillfully used the contradictions between the high clergy and the secular nobility, as well as the hostility of the German prelates to the Roman Curia, in order to more closely subordinate the German episcopate to his power. Of course, there could no longer be any talk of reviving the Ottonian episcopal system. In the fight against the Welfs, Frederick I relied on German magnates who were hostile to the expansionist policy of this dynasty. All this made it possible, despite the intensive growth of princely territorial domination in the country, to strengthen the position of royal power for some time. The consistently applied principles of vassalage increased the dependence of the princes on the emperor, in particular in the military field, and strengthened the national military organization. The king's dominance over the church increased. Without formally violating the Concordat of Worms, Barbarossa interfered in church elections, appointing his proteges to the posts of bishops and abbots. He sought to weaken the dependence of the German prelates on the Roman Curia, creating all sorts of obstacles to their appeals to the pope. Of course, the emperor's attempts to consider bishops in the spirit of the Carolingian tradition as civil servants had no real basis. Bishops, like secular princes, remained only royal vassals. However, Barbarossa demanded more from them than they were accustomed to do for the benefit of the state: he considered the secular investiture of prelates not an act of mercy, but a royal authority. The legislation of Frederick I, although based on the principles of vassal-fief relations, required the feudal lords, under the threat of severe administrative penalties, to fulfill their public duty. Continuing the policy of strengthening the land peace begun by Henry IV, Frederick I achieved the introduction of general peace in the country, establishing severe punishments for violators.

However, an analysis of the peace law of 1152 shows that punitive measures were directed primarily against the masses who fought against the violence of the oppressors. Peasants were prohibited from carrying weapons. Access to the knightly army was completely denied to them. Chivalry turned into a closed class. Now, in addition to noble persons of the “knightly rank,” only ministerials who had risen in class could become knights.

The foreign policy position of the German Empire significantly strengthened. As mentioned above, in addition to the Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary were involved in the orbit of German influence. The Hungarian king took part in Barbarossa's second campaign in Italy in 1158. Burgundy's dependence increased as a result of Frederick I's second marriage to Countess Beatrice of Upper Burgundy. This improved the strategic position of the empire on the Italian border.

Thus, in the second half of the 12th century, domestic and foreign policy conditions developed to strengthen German hegemony in Western, Central and Southern Europe and to increase the prestige of the “Holy Roman Empire”. It was at this time that a new title of the medieval German Empire appeared. She began to be called Sacred.

The imperial doctrine of the Holy Empire, which was theoretically substantiated by Otto of Freisingen, was directed against the pope, who considered himself to have the right to dispose of the crown of the Roman emperors and invest it as “benefits” to the German king. It was argued that the empire was sacred even without the fact that the imperial crown was formally placed on the head of the emperor by the pope. The head of the empire is absolutely sovereign in the exercise of secular power, he obeys only God, and no one on earth, and wields the “secular sword” regardless of the pope. Moreover, he is called upon to defend with this sword the Christian Church and the Pope himself. The imperial office and official historiography promoted the idea that the emperor rules the world by “divine mandate”, that he is “the viceroy and minister of God.” Imperial propaganda sought in every possible way to downplay the significance of the papal coronation in Rome and emphasized the role of princely election and anointing to the throne, which gave the monarchy a sacred and sovereign character. German kings, even before receiving the imperial crown in Rome, were officially called by the titles - “King of the Romans”, “August King of the Romans” (rex Romanorum, rex Romanorum semper augustus).

To substantiate his claims to dominance over the cities of Northern Italy and Rome, Barbarossa turns to Roman law. In legislative acts for Italy there are provisions borrowed from the Code of Justinian: “Your will is the law, for it is said: whatever pleases the sovereign has the force of law,” “it is appropriate that the imperial dignity should be protected not only by force of arms, but also by law,” “the sovereign’s law does not limit." These reminders of Roman law were reinforced by references to the right of conquest. Thus, in the response of Frederick Barbarossa to a letter from the Roman Senate, it was indicated that Italy and Rome were conquered by Charlemagne and Otto I and belonged to the emperor by right of conquest. The well-known theory of “transfer of empire” (translatio imperium), with the help of which the claims of the German emperor to world domination were justified, was interpreted in a similar spirit. In the papal interpretation, the “transfer of the empire” is carried out at the will of the papal throne, which was allegedly granted the “gift of Constantine” with supreme power over western part empires. Leo III handed over this power, along with the Roman crown, to Charlemagne. In the 10th century, the Roman throne was transferred by the pope to the German kings, but it can be returned and transferred by the curia to another sovereign, for example, the Byzantine emperor - the true successor of the ancient Roman emperors. The Staufen propaganda countered this papal version of the “transfer of the empire” with its own: imperial power in the West was restored as a result of conquest, and the German (Roman) king uses it independently of the pope.

The Roman and Carolingian tradition served as a tool for the foreign policy expansion of the German emperors. According to Otto of Freisingen, the "transfer of empire" from the Western to the Eastern Franks did not in any way change the character of that empire. The emperor retained his prerogatives within the former Frankish state, that is, in its western part. This was how the claims to supremacy over France were justified. Frederick Barbarossa's letters to the French king Louis VII emphasized that the German-Roman emperor retained the supreme rights inherited from Charlemagne throughout the Carolingian Empire.

In this regard, one should consider the canonization of Charlemagne undertaken by Barbarossa in 1166 and the declaration of Aachen as a holy city.

The aggressive aspirations of Frederick Barbarossa extended to the east. He considered it no longer enough to equal the title of the Byzantine emperor, but claimed superiority over “Eastern Rome.” In the messages to the Byzantine court, the idea was conveyed that the emperor of the “Holy Roman Empire” was the successor of the Roman emperors, who at one time owned the eastern part of the empire. It goes without saying that such statements were very far from reality. But we must take into account the fact that this expansionist ideology determined the foreign policy course of the “Holy Empire.” It is characteristic that with the weakening of the power of the emperors within Germany itself, this course became increasingly aggressive.

Quoted from: All the wars of world history according to the Harper's Encyclopedia of Military History by R.E. Dupuis and T.N. Dupuis. Book two. 1000-1500 St. Petersburg, 2004, p. 44-49.

Contemporaries describe him as a man slightly above average height, well built and in good health. He had a friendly face that endeared him to his interlocutors; it seemed that he was always ready to smile. Light slightly curly hair, a straight nose, thin lips and a row of snow-white teeth, as well as a red beard, which gave him his nickname - this is how his appearance is remembered. Frederick I Barbarossa had a sharp mind, was fair and reasonable. He could not be accused of excessive wastefulness or stinginess. He did not refuse to follow advice if he found it useful, and often showed leniency towards petitioners. At the same time, his temperament sometimes prevailed over prudence: in moments of anger, he could show extreme cruelty. However, this is not what made Barbarossa famous; the morals and traditions of that era were significantly different from those of today, and it cannot be argued that, compared to other powers that be, the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire embodied a bloodthirsty monster.

The future 21st Holy Roman Emperor was born at the end of 1122 (the exact date is unknown), his father was Frederick II "One-Eyed", Duke of Swabia, from the Hohenstaufen (Staufen) family, his mother was Judith, daughter of the Duke of Bavaria Henry IX the Black of antique German family Welfov. In addition, Frederick Barbarossa had family ties with another ancient family - the Babenbergs. Here it should immediately be noted that Frederick Barbarossa, as the Duke of Swabia, who inherited the duchy after the death of his father in 1147, is referred to as “Frederick III”, and as the King of Germany, which he became in 1152 and the Roman Emperor (1155). ) he is called "Frederick I".

The father of the future emperor also laid claim to the royal throne, but contrary to expectations, his rival, Lothair, Duke of Saxony, was elected king. At first, Frederick II recognized Lothair as king, but a dispute over the possessions of the previous king Henry V, with whom the Duke of Swabia was related, soon made Frederick II and Lothair irreconcilable enemies. It was precisely in the wars with the king that the Duke of Swabia lost one eye, which, according to the laws of that time, finally put an end to the possibility of Frederick II ever placing the crown on himself. As a result, after the death of Lothair, the brother of Frederick One-Eye, Conrad III Duke of Franconia (King of Germany from 1138 to 1152), was elected king, who appointed Frederick Barbarossa as his successor, since the eldest son of Conrad III, Henry Berengar, who was preparing to become the heir to the throne, died in 1150 The youngest son of Conrad III, Duke Frederick of Rothenburg, was seven years old at that time, and it was clearly too early for him to rule the kingdom. Conrad III noted the talents of his nephew, who was constantly with him in the last years of his life. Moreover, he rightly believed that Frederick, having become king, would be able to reconcile the Staufens with the Welfs, who had long been disputing power in the kingdom.

Thirty-year-old Frederick had by that time taken part in the second crusade (1147 - 1149), where he attracted attention as a brave and valiant warrior. The campaign itself did not bring success to the crusaders: lost battles, the unsuccessful siege of Damascus, disagreements in the camp of the Christian army - all this led to the fact that the remnants of the armies of Conrad III and the French king Louis VII returned home ingloriously, but, of course, the future emperor gained invaluable experience , both military and political.

On February 4, 1152, in Frankfurt, Frederick Duke of Swabia was elected king of Germany and was crowned in Aachen on March 9. The Kingdom of Germany was then the core of the Holy Roman Empire, therefore, Frederick I was preparing to become emperor, and the German episcopate insisted on an immediate trip to Italy for the imperial coronation. Nevertheless, on the advice of secular princes, Frederick dealt primarily with German problems, and sent an embassy to Rome with a letter to Pope Eugene III. The Pope at that time was in dire need of the support and protection of the emperor, since the Sicilian Normans threatened Rome from the south, and in Rome itself it was also not calm - criticism of Arnold of Brescia set the townspeople against the order that reigned in the environment of the papal throne. But the new king of Germany, from the first days of his reign, set a course for the liberation of secular power from the hegemony of the church, so he himself was in no hurry to go to Rome, but preferred to first surround himself with devoted people capable of realizing with him his main dream - to revive the former glory of the Empire and the greatness of the emperor. Among those close to him were Count Otto Wittelsbach, appointed standard bearer of the Empire, as well as the provost of the Hildesheim Church, Rainald von Dassel, a man as smart and learned as he was ambitious.

The next step of Frederick I was to carry out personnel reform in the German Curia. The king's ambassadors managed to convince the pope that the hierarchy of the German church should be updated. Thus, it was possible to remove Archbishop Heinrich of Mainz, an ardent opponent of the king, and the bishops of Eichstedt, Minden, and Hildesheim - all of them were replaced by people loyal to the emperor. Even earlier, Frederick appointed Wichmann, who was the bishop of Naumburg and also part of the circle of those close to the king, as Archbishop of Magdeburg.

In addition to permission to renew the German clergy, in exchange for a promise to the Pope to arrive in Rome in a year for the coronation, Frederick I asked him to dissolve his marriage with the daughter of Diapold III of the Margrave of Voburg, Adelheide. This marriage brought nothing to Frederick except the increase of the king's territorial possessions by including the hereditary estates of the countess. There was no love and harmony between the spouses, and Frederick decided to separate from his unloved wife, which happened in March 1153. The reason for the dissolution of this marriage was the relationship of the spouses: Frederick’s great-grandfather was the brother of his great-grandmother Adelheide of Voburg. Such a relationship can hardly be considered too close, but Pope Eugene III considered it sufficient. Eugene III, of course, pursued his own interests and thereby wanted to oblige the king.

Before heading to Italy, Frederick managed to settle several more important matters in Germany. He established a relationship with Count William of Macon, who at that time actually assumed guardianship of the daughter of the Count Palatine of Burgundy, Renault III. Despite the fact that Burgundy was promised as a fief to Duke Berthold IV of Zähringen, Frederick recognized William as his guardian, and he, in turn, took a vassal oath to the king. The fulfillment of the promise to Zähringen was delayed indefinitely. There was also a Bavarian problem: the duchy of Bavaria was claimed by the king’s cousin Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony from the Welf family, and Heinrich Jazomirgot from the Babenberg family, who was Frederick’s uncle. The meeting with Yazomirgot did not bring the desired result; he categorically refused to transfer Bavaria to Henry the Lion. And the support of his cousin was extremely important to the king, so at the Reichstag in Goslar, where Yazomirgot did not appear, it was decided to transfer Bavaria to Henry the Lion. The Duke of Saxony demanded more - he wanted to gain the right of supreme suzerainty over the church in his duchy, and the king made concessions, realizing how dependent he was on his cousin. Only after these issues were resolved, Frederick was able to go to Rome to claim the emperor's crown.

It is necessary to say a few words about the Holy Roman Empire, since all of Barbarossa’s main activities until the end of his days were connected with strengthening the power of the emperor of this state entity, and it is believed that it was under Frederick I that the empire reached its heyday and military power.

The Holy Roman Empire was founded in 962 by King Otto I the Great and it claimed to be a continuation of the ancient Roman Empire and even more so - as a state uniting the entire Christian world, or rather the Western Christian world. Initially, the concept of the new empire was as follows: the unity of state and church, almost the embodiment of the Kingdom of God on earth, in which a wise ruler, together with the Pope, takes care of the prosperity of his subjects, maintains calm and protects the world, being the protector of Christians. However, in reality, an uncompromising struggle often took place between the highest clergy and representatives of secular power. Formally, Rome was considered the capital of the empire, but at best it can be considered as a sacred center, because the core of the empire was always Germany. In addition to Germany, the empire included Italy, Burgundy, and somewhat later, from 1135, the kingdom of the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, and Austria. Having existed until 1806, the empire was never able to become a unified state in in every sense this word. It always remained a decentralized entity, where the power of the emperor was not absolute, and the subjects that were nominally part of the empire had sufficient independence. In general, Friedrich had something to do, fortunately, he was energetic and power-hungry by nature.

Frederick's first Italian campaign can be conditionally called "reconnaissance in force." In fact, the king at that time assembled a small army, half of which were the knights of Henry the Lion, since most German feudal lords did not feel any desire to fight with Italian cities, not seeing any direct benefit for themselves. At the end of October 1154, Frederick crossed the Alps. The Italians greeted Frederick with caution - it seemed like the emperor had come, but it was unclear what to expect from him. They were in no hurry to greet him with bread and salt, which is why the Germans sometimes had to forcefully provide themselves with provisions and fodder.

Even before his coronation in Rome, Frederick began to restore order in the Italian lands controlled by the empire, settling with his army on the Roncal fields. There he assembled his first Reichstag in Italy, took the oath from those cities of northern Italy that were ready to recognize him as their emperor, and administered court, since there was no unity between the cities themselves. So, following a complaint from the citizens of Pavia, the newly-minted emperor called Tortona to account, and having received a refusal to obey from its inhabitants, who hoped for the help of Milan, Frederick besieged the rebellious city in mid-February. Milan indeed sent a hundred knights and two hundred archers to help the Tortonians, but already in April the city surrendered, the residents were ordered to leave it, after which Tortona was plundered and burned.

After the defeat of Tortona, Frederick visited Pavia, where he placed the Lombard crown on his head, and then visited Bologna, famous for its school of jurisprudence. The king granted the Bologna school a special privilege: he forbade the residents of Bologna to collect the debts of fugitive schoolchildren from their comrades. This put an end to the arbitrariness of the Bolognese innkeepers, who profited from the school.

By the beginning of summer, Frederick approached Rome. By that time, there had already been two popes on the throne of St. Peter - Eugene III and his successor Anastasius IV. Adrian IV, a convinced Gregorian and supporter of the dogma of the supremacy of spiritual power over secular power, was elected as the new pope. This did not bode well for Frederick's future, but the king and the pope needed each other. Even before Frederick arrived, Adrian sent legates to him with the intention of finding out whether the king confirmed the agreements concluded with Eugene III. Frederick confirmed the Treaty of Constance of 1153, and also fulfilled the request to extradite Arnold of Bershian, who was hiding in the mountains of Tuscany at that time, to the pope. The meeting of the pope with the future emperor took place on June 8 near Rome, and almost immediately escalated into a conflict. Frederick refused to perform the “master of horse” service - symbolizing the submission of a vassal to his lord, and in response Adrian refused Frederick the kiss of peace. The coronation was in jeopardy. Frederick had to humble his pride, but the pope harbored distrust of the German monarch, even despite the fact that Frederick tried to prove the opposite a few days later. When the Roman Senate proposed to accept the crown of Emperor Frederick from the Roman people, and not from the Pope, and in addition to approve some customs and new institutions, the king attacked them with an angry rebuke.

The coronation took place secretly from the Romans on June 18, 1155 in St. Peter's Basilica. It is noteworthy that already in the evening after the coronation there was a bloody battle on the streets of Rome - the Romans attacked Frederick’s troops, and although the attack was repulsed, the next day Frederick, and at the same time the Pope, left the city.

On Frederick's return to Germany, the Emperor's wrath fell on the city of Spoleto, whose residents decided to cheat and pay the "fondrum" - a tax levied on the occasion of the coronation with counterfeit money. And in September, Frederick had to fight with Verona, which refused to recognize Frederick as its emperor. But Milan remained the main center of resistance, and Frederick could not take this well-fortified city; for this it was necessary to gather enough forces and enlist the support of the allies.

The only achievement of Frederick's first Italian campaign (except for the acquired nickname - barba - beard and rossa - red) was the crown of the emperor, but the cities of northern Italy were still not completely subordinate to the Emperor. To establish his power in Italy, Frederick needed to strengthen his position in Germany, because only in this way could he rally the German princes around himself, and, therefore, gather enough forces for a new campaign against the rebellious Italians. To do this, first of all, he needed to reconcile the Duke of Saxony, Henry the Lion, who by that time had been granted Bavaria at the Reichstag in Regensburg in October 1155, with Heinrich Jazomirgot. The latter still did not renounce his rights to the Duchy of Bavaria, and this threatened a new conflict. In June 1156, an agreement was reached with Henry Yazomirgot. As compensation, Barbarossa granted Yazomirgot the Duchy of Austria, separating it from the Bavarian lands with a deed of gift on September 17, 1156. This document proclaimed the almost complete independence of Austria from Bavaria, established the right of inheritance of the Duchy of Austria by the Babenberg dynasty, as well as the possibility of appointing his successor as duke. It would seem that Frederick thereby weakened royal power by separating Austria from the empire and giving Henry the Lion two duchies at once - Saxony and Bavaria, but in fact he managed to solve a serious internal political problem peacefully. He turned potential enemies of the crown into his allies, which gave him the opportunity to re-engage with Italy.

In June 1156, the Emperor celebrated his wedding. The second wife of Frederick Barbarossa was Beatrice I, daughter of Count Palatine of Burgundy Renault III. This marriage, concluded on June 10, 1156, can be considered happy. The couple lived together for 28 years until the death of Empress Beatrice in 1184, having had eleven children - eight sons, one of whom later became emperor under the name of Henry VI, and the other, Philip, was king of Germany from 1198 to 1208. , and three daughters. Together with his bride, Frederick also received a huge dowry, consisting of Burgundian territories with Alpine passes that opened the way to Italy. In addition, Frederick consolidated his power in Burgundy, which until that time had been part of the empire only formally.

If Frederick managed to temporarily reconcile the German feudal lords, gain authority and enlist their support, then his relationship with the spiritual authorities clearly did not work out. In October 1157, the Reichstag was held in the city of Besançon, where the legates of the Pope arrived with a message to the emperor. The message was translated from Latin by Rainald von Dassel. It is possible that he deliberately translated the word “beneficium” as “flax” and not as “benefit,” and the meaning of the Pope’s message became as follows: none other than the Pope endowed Frederick with power, and that ungrateful person completely forgot about such mercy and did not provides the Pope with no support. Adrian IV had reasons for reproach; after the coronation, Frederick Barbarossa left Italy, and the pontiff himself had to resolve issues with the Roman Senate and establish relations with King William the Evil - the King of Sicily. And the reason was the emperor’s refusal to investigate the attack on the Archbishop of Lund, to whom the Pope had transferred the leadership of the Swedish Church. Frederick had a completely different opinion regarding his election to the throne. The emperor believed that he owed this to the mercy of God and the will of the German princes. The papal ambassadors were almost mutilated, and only the personal intervention of Frederick Barbarossa saved them from reprisals. However, they were removed from the Reichstag. Adrian tried to influence the obstinate monarch through the German episcopate, but he supported the emperor. The pope had to back down, send a new message with explanations, but at the same time he himself entered into an agreement with the Lombard cities and the Sicilian king. Only the sudden death of Adrian IV saved Frederick Barbarossa from anathema, but the conflict with the church did not end there.

In 1158, the emperor again crossed the Alps with the goal of subjugating Milan, which had become a kind of stronghold of all opponents of the empire in Lombardy. This time, Barbarossa managed to prepare well - he enlisted the support of many German feudal lords and assembled a large army. The result was not long in coming; in less than a month, unable to withstand the siege, Milan surrendered to the mercy of the winner. This happened significant event September 1, 1158 The Milanese were forced to pay tribute and hand over all the hostages. Milan was also denied the right to mint coins and collect tolls. A castle was built in the center of the city, and a garrison loyal to the emperor was left in it. It seemed that victory was achieved with little blood once and for all.

In November 1158, the Reichstag, a state assembly, was held in Roncale, where the principles of governing the newly annexed possessions were set out. From now on, control over public roads, navigable rivers, ports and harbors was exercised by imperial officials, and the minting of coins and collection of taxes became the exclusive imperial prerogative. Any internecine wars were prohibited, on pain of confiscation of fiefs from all those who violated this ban; in addition, the emperor demanded strict observance of military service.