THE LOOK OF CITY STREETS

Pavements in Paris appeared in the 12th century - every citizen had to make sure that the street in front of his house was paved. This measure was then extended by the 14th century by royal order to other French cities. But, for example, in Augsburg there were no pavements until almost the 15th century, as well as sidewalks. Drainage ditches appeared only in the XIV-XV centuries, and then only in large cities.

Garbage and sewage in cities was usually dumped into rivers or into nearby ditches. Only in the XIV century. urban scavengers appeared in Paris.

FThe eudal city bears little resemblance to the modern one. It is usually surrounded by walls, which it needed to protect itself from enemy attacks, to give shelter to the rural population in case of invasions.

The inhabitants of the city, as already mentioned, had their gardens, their fields, their pastures. Every morning, at the sound of the horn, all the gates of the city were opened, through which the cattle were driven out to the communal pastures, and in the evening these cattle were again driven into the city. In the cities they kept mainly small livestock - goats, sheep, pigs. The pigs were not driven out of the city, they found plenty of food in the city itself, since all the garbage, all the remnants of food were thrown right there into the street. Therefore, there was an impossible dirt and stench in the city - it was impossible to walk along the streets of a medieval city without getting dirty in the mud. During the rains, the streets of the city were a swamp in which carts got stuck and sometimes a rider with a horse could drown. In the absence of rain, it was impossible to breathe in the city because of the caustic and fetid dust. Under such conditions, epidemic diseases in the cities were not transmitted, and during the great epidemics that flared up from time to time in the Middle Ages, the cities suffered the most. Mortality in the cities was unusually high. The population of cities would decrease continuously if it were not replenished with new people from the villages.

the essence of the enemy. The population of the city carried out guard and garrison service. All the inhabitants of the city - merchants and artisans - were able to wield weapons. City militias often inflicted defeat on the knights. The ring of walls behind which the city was located did not allow it to grow in breadth.

Gradually, suburbs arose around these walls, which in turn also strengthened. The city thus developed in the form of concentric circles. The medieval city was small and cramped. In the Middle Ages, only a small part of the country's population lived in cities. In 1086, a general land census was carried out in England. Judging by this census, in the second half of the XI century. in England, no more than 5% of the total population lived in cities. But even these townspeople were not yet quite what we understand by urban population. Some of them were still engaged in agriculture and had land outside the city. At the end of the XIV century. in England a new census was made for tax purposes. It shows that already about 12% of the population at that time lived in cities. If we move from these relative figures to the question of the absolute number of urban population, we will see that even in the XIV century. cities with 20 thousand people were considered large. On average, there were 4-5 thousand inhabitants in cities. London, in which in the XIV century. there were 40 thousand people, was considered a very large city. At the same time, as we have already said, most cities are characterized by a semi-agrarian character. There were many "cities" and purely agrarian type. They also had crafts, but rural crafts prevailed. Such cities differed from villages mainly only in that they were walled and presented some features in management.

Since the walls prevented cities from expanding in breadth, the streets were narrowed to the last degree to accommodate the possible pain. better order ny, the houses hung over each other, the upper floors protruded above the lower ones, and the roofs of the houses located on opposite sides of the street almost touched each other. Each house had many outbuildings, galleries, balconies. The city was cramped and crowded with residents, despite the insignificance of the urban population. The city usually had a square - the only more or less spacious place in the city. On market days, it was filled with stalls and peasant carts with all kinds of goods brought from the surrounding villages.

Sometimes there were several squares in the city, each of which had its own special purpose: there was a square where grain trade took place, on another one they traded hay, etc.

CULTURE (HOLIDAYS AND CARNIVALS)

Among the definitions that scientists give to a person - "reasonable person", "social being", "working person" - there is also this: "playing person". "Indeed, the game is an integral feature of a person, and not just a child. People of the medieval era loved games and entertainment just as much as people at all times.

Harsh living conditions, heavy piles, systematic malnutrition were combined with holidays - folk, which dated back to the Pagan past, and church, partly based on the same Pagan tradition, but transformed and adapted to the requirements of the church. However, the attitude of the church towards folk, primarily peasant, festivities was ambivalent and contradictory.

On the one hand, she was powerless to simply ban them - the people stubbornly held on to them.

It was easier to bring the national holiday closer to the church one. On the other hand, throughout the Middle Ages, clergy and monks, referring to the fact that "Christ never laughed", condemned unbridled fun, folk songs and dances. dances, the preachers asserted, the devil invisibly rules, and he carries away the merry people straight to hell.

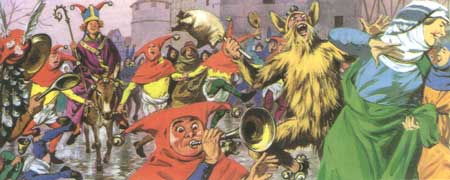

Nevertheless, fun and celebration were ineradicable, and the church had to reckon with this. jousting tournaments, no matter how askance the clergy looked at them, remained a favorite pastime of the noble class. By the end of the Middle Ages, a carnival took shape in the cities - a holiday associated with seeing off winter and welcoming spring. Instead of unsuccessfully condemning or forbidding the carnival, the clergy preferred to take part in it.

During the days of the carnival, all prohibitions on fun were canceled and even religious rites were ridiculed. At the same time, the participants in the carnival buffoonery understood that such permissiveness was permissible only during the days of the carnival, after which the unbridled fun and all the outrages that accompanied it would stop and life would return to its usual course.

However, it happened more than once that, having begun as a fun holiday, the carnival turned into a bloody battle between groups of wealthy merchants, on the one hand, and artisans and urban lower classes, on the other.

The contradictions between them, caused by the desire to take over the city government and shift the burden of taxes on opponents, led to the fact that the carnival participants forgot about the holiday and tried to deal with those whom they had long hated.

LIFE (SANITARY CONDITION OF THE CITY)

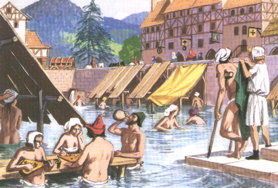

Due to the overcrowding of the urban population, the many beggars and other homeless and homeless people, the lack of hospitals and any regular sanitary supervision, medieval cities were constantly breeding grounds for all kinds of epidemics.

The medieval city was characterized by a very unsanitary condition. The narrow streets were quite stuffy. They were mostly unpaved. Therefore, in hot and dry weather in the city it was very dusty, in inclement weather, on the contrary, it was dirty, and carts could hardly pass through the streets and passers-by made their way.

In settlements there is no sewerage for dumping sewage. Water is obtained from wells and stagnant springs, which often get infected. Disinfectants are not yet known.

In settlements there is no sewerage for dumping sewage. Water is obtained from wells and stagnant springs, which often get infected. Disinfectants are not yet known.

Due to the lack of sanitation, women in labor often do not survive difficult births, and many babies die in their first year of life.

For the treatment of simple diseases, they use grandmother's recipes, usually based on medicinal herbs.

In severe cases, the sick decide on bloodletting, which is done by a barber, or they buy drugs from a pharmacist. The poor go to the hospital for help, but the tightness, inconvenience, and dirt leave the seriously ill with almost no chance of surviving.

URBAN POPULATION

The main population of medieval cities were artisans. They became peasants who fled from their masters or went to the cities on the terms of payment of dues to the master. Becoming townspeople, they gradually freed themselves from excellent dependence on the feudal lord. If a peasant who fled to the city lived in it for a certain period, usually one year and one day, then he became free. A medieval proverb said: "City air makes you free." Only later did merchants appear in the cities. Although the bulk of the townspeople were engaged in crafts and trade, many residents of the city had their fields, pastures and gardens outside the city walls, and partly within the city. Small livestock (goats, sheep and pigs) often grazed right in the city, and the pigs ate garbage, leftover food and sewage, which were usually thrown directly into the street.

Craftsmen of a certain profession united within each city into special unions - workshops. In Italy, workshops arose already from the 10th century, in France, England, Germany and the Czech Republic - from the 11th-12th centuries, although the final registration of workshops (obtaining special charters from kings, writing workshop charters, etc.) took place, as a rule , later. In most cities, belonging to a guild was a prerequisite for doing a craft. The workshop strictly regulated production and, through specially elected officials, ensured that each master - a member of the workshop - produced products of a certain quality. For example, the weaver's workshop prescribed what width and color the fabric should be, how many threads should be in the warp, what tool and material should be used, etc. The workshop charters strictly limited the number of apprentices and apprentices that one master could have, they forbade work at night and on holidays, limited the number of machines for one artisan, and regulated the stocks of raw materials. In addition, the guild was also a mutual aid organization for artisans, providing assistance to its needy members and their families at the expense of an entrance fee to the guild, fines and other payments in case of illness or death of a member of the guild. The workshop also acted as a separate combat unit of the city militia in case of war.

In almost all the cities of medieval Europe in the 13th-15th centuries, there was a struggle between craft workshops and a narrow, closed group of urban rich (patricians). The results of this struggle varied. In some cities, primarily those where craft prevailed over trade, workshops won (Cologne, Augsburg, Florence). In other cities where merchants played a leading role, handicraft workshops were defeated (Hamburg, Lübeck, Rostock).

Jewish communities have existed in many old cities of Western Europe since the Roman era. Jews lived in special quarters (ghettos), more or less clearly separated from the rest of the city. They were usually subject to a number of restrictions.

THE STRUGGLE OF CITIES FOR INDEPENDENCE

Medieval cities always arose on the land of the feudal lord, who was interested in the emergence of a city on his own land, since crafts and trade brought him additional income. But the desire of the feudal lords to get as much income from the city as possible inevitably led to a struggle between the city and its lord. Often, cities managed to obtain the rights of self-government by paying a large sum of money to the lord. In Italy, cities achieved great independence already in the 11th-12th centuries. Many cities of Northern and Central Italy subjugated significant surrounding areas and became city-states (Venice, Genoa, Pisa, Florence, Milan, etc.)

In the Holy Roman Empire, there were so-called imperial cities, which were actually independent city republics since the 12th century. They had the right to independently declare war, make peace, mint their own coin. Such cities were Lübeck, Hamburg, Bremen, Nuremberg, Augsburg, Frankfurt am Main and others. The symbol of the freedom of the cities of the Holy Roman Empire was the statue of Roland.

Sometimes large cities, especially those located on royal land, did not receive the rights of self-government, but enjoyed a number of privileges and liberties, including the right to have elected city government bodies. However, such bodies acted jointly with the representative of the seigneur. Paris and many other French cities had such incomplete rights of self-government, for example, Orleans, Bourges, Lorris, Lyon, Nantes, Chartres, and in England - Lincoln, Ipswich, Oxford, Cambridge, Gloucester. But some cities, especially small ones, remained entirely under the control of the seigneurial administration.

CITY SELF-GOVERNMENT

Self-governing cities (communes) had their own court, military militia, and the right to levy taxes. In France and England, the head of the city council was called the mayor, and in Germany, the burgomaster. The obligations of commune cities towards their feudal lord were usually limited only to the annual payment of a certain, relatively low amount of money and sending a small military detachment to help the lord in case of war.

The municipal government of the urban communes of Italy consisted of three main elements: the power of the people's assembly, the power of the council and the power of the consuls (later the podestas).

Civil rights in the cities of northern Italy were enjoyed by adult male homeowners with property subject to taxation. According to the historian Lauro Martinez, only 2% to 12% of the inhabitants of the northern Italian communes had the right to vote. According to other estimates, such as those given in Robert Putnam's book Democracy in Action, 20% of the city's population had civil rights in Florence.

After an attempt to subjugate Milan (1158) and some other cities of Lombardy, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa introduced a new post of podest-mayor in the cities. Being a representative of the imperial power (regardless of whether he was appointed or approved by the monarch), the podesta received the power that previously belonged to the consuls. He was usually from another city so that local interests would not influence him. In March 1167, an alliance of Lombard cities arose against the emperor, known as the Lombard League. As a result, the political control of the emperor over the Italian cities was effectively eliminated and the podestas were now elected by the citizens.

Usually, a special electoral college, formed from members of the Grand Council, was created to elect the podest. She had to nominate three people who are worthy to govern the Council and the city. The final decision on this issue was taken by the members of the Council, who elected the podestas for a period of one year. After the end of the term of office of the podest, he could not apply for a seat on the Council for three years.